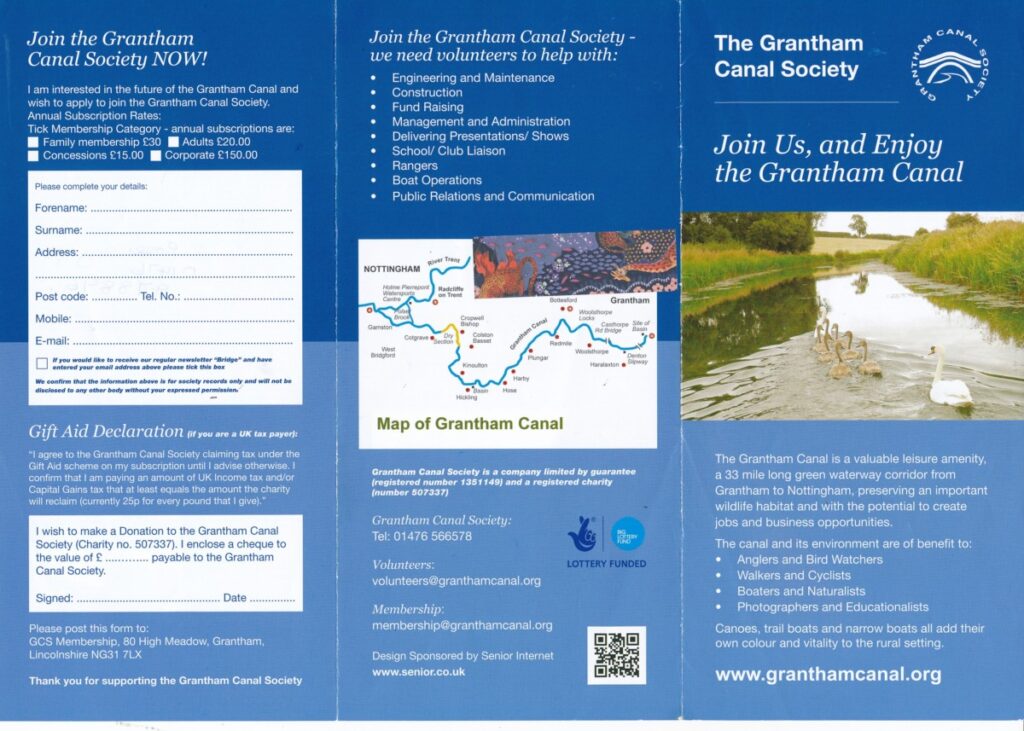

In Maps:

Introduction:

The Grantham Canal was commissioned by subscription in the 1790s being formalised by Acts of Parliament in 1793 and 1797; this was the time of a huge national canal-building programme – 19 were given consent in 1793 alone. A full history is someone else’s (huge) task but the construction of this 33-mile waterway through the countryside between Nottingham and Grantham fundamentally changed the rural communities that it passed through – the historic combination of Enclosure Acts and the Industrial Revolution changing the rural economy and rural communities.

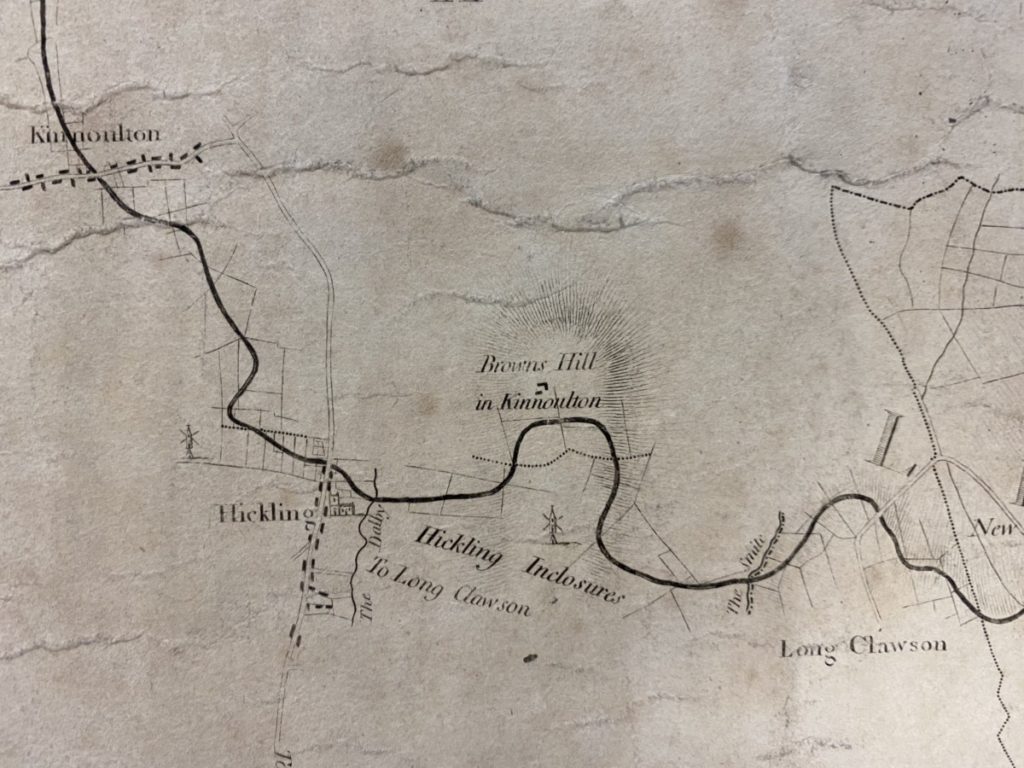

- The canal ‘flows’ from east (Grantham) to west (Nottingham); the level only drops by a few inches as it passes through Hickling, though.

- The water levels are controlled by two reservoirs; Denton and Knipton with rainfall being the third contributing factor.

- When the canal was built it was given a thin layer of clay to seal the water in* – this skin is the most vulnerable element as it becomes damaged over time by tree roots, ground movement and accidentally during maintenance work.

- Sadly, the Grantham Canal always struggled to be viable; its most profitable years came in the early 1800s but water levels have been problematic throughout its existence (strong weed growth, the build-up of silt, the gypsum section around Cropwell Bishop & Cropwell Butler and (latterly) lack of use) making the route unreliable.

- The coming of the railways in the mid-1800s precipitated a slow decline in the commercial use of the canal and meant that its active years were relatively short; by the end of the 1800s, the canal was in severe decline and by the early-1920s its working life was over.

- In 1936 a further Act of Parliament formally closed the canal to boats (there had been no traffic on it for the previous 7 years). This had two major effects:

- Financial responsibilities were massively reduced because ongoing maintenance requirements were minimised;

- But also, the waterway was to be deliberately allowed to evolve as a wildlife corridor and for the quiet enjoyment of visitors. Some stretches have been designated as SSSIs and the Hickling stretch is designated as a local wildlife site.

- (the Act also stated that water should be kept to a depth of 2 feet and could be used for agricultural purposes (irrigation and drinking water for animals))

- The Transport Act of 1968 categorised the Grantham Canal as a ‘remainder waterway’ with no economic future. In 1969 proposals were made to close and infill most of the canal:

- “The proposal to close and infill most of the canal was strongly contested by the “Grantham Civic Trust” and the Grantham Angling Association. Ultimately, with the support of the Inland Waterways Association and the MP for Carlton, Mr Phillip Holland, the canal was saved. The Grantham Canal Society was then formed, later to be called the Grantham Canal Restoration Society.” (The Grantham Canal: Meander p.28)

*This process was known as ‘puddling’ – there’s a lovely photograph on page 21 of ‘The Grantham Canal: Meander’ which shows a herd of cows being driven up and down the bottom of the canal bed to ‘puddle’ in the clay layer.

The Construction Years:

- The building of the canal was a significant business enterprise; it had to be privately funded and subscribers and shareholders had to be found. Some of these shareholders would have been significant but they also included small investors who had a local interest.

- Georgian & Victorian literature is peppered with references to investments having been lost through schemes which failed and previously rich families finding themselves in impoverished circumstances (The Miss Bateses in Jane Austen’s ‘Emma’, for example) – this was one of these schemes but, fortunately, it did prove viable and there are no signs that anyone lost significant sums of money as a result!

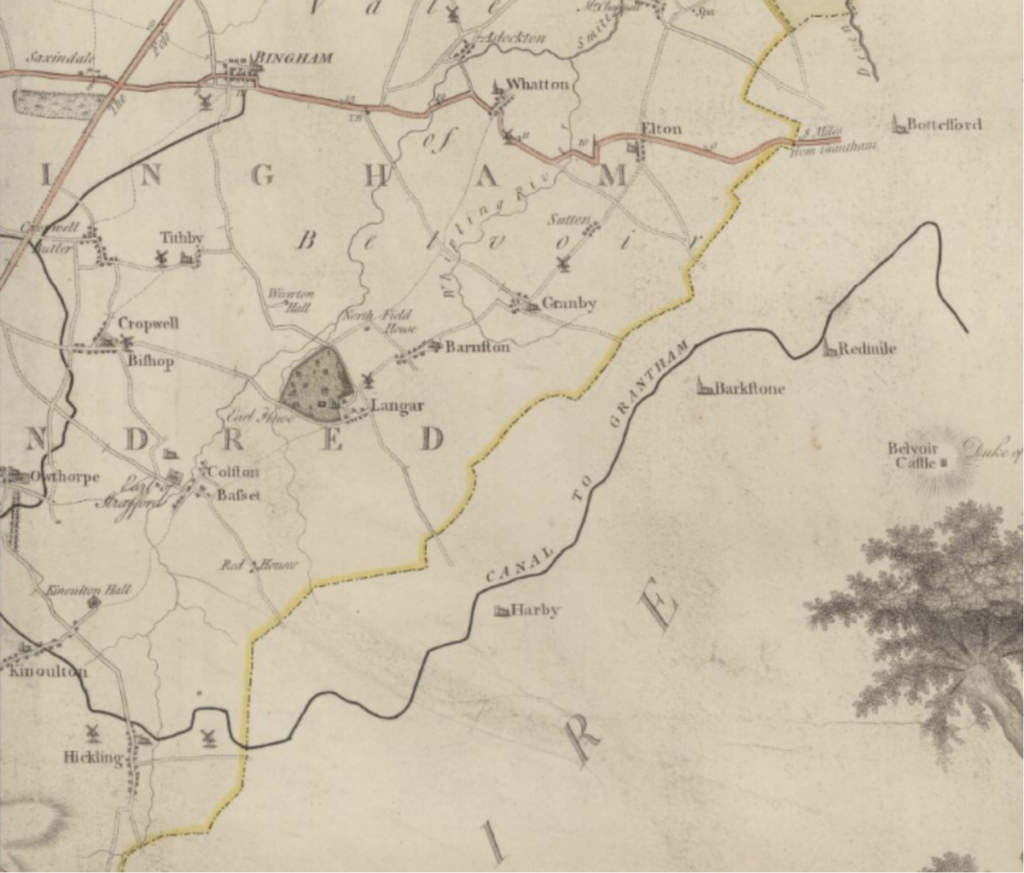

- The plans went through many changes and the route was determined by the landscape and geology of the area and also by the business interests of the investors and prospective customers. A diversion was made to accommodate the Belvoir Estate and an off-shoot to Bingham was proposed but never happened.

- Please see the bibliography (bottom of the page) – there are some excellent histories which fill out the detail of these years.

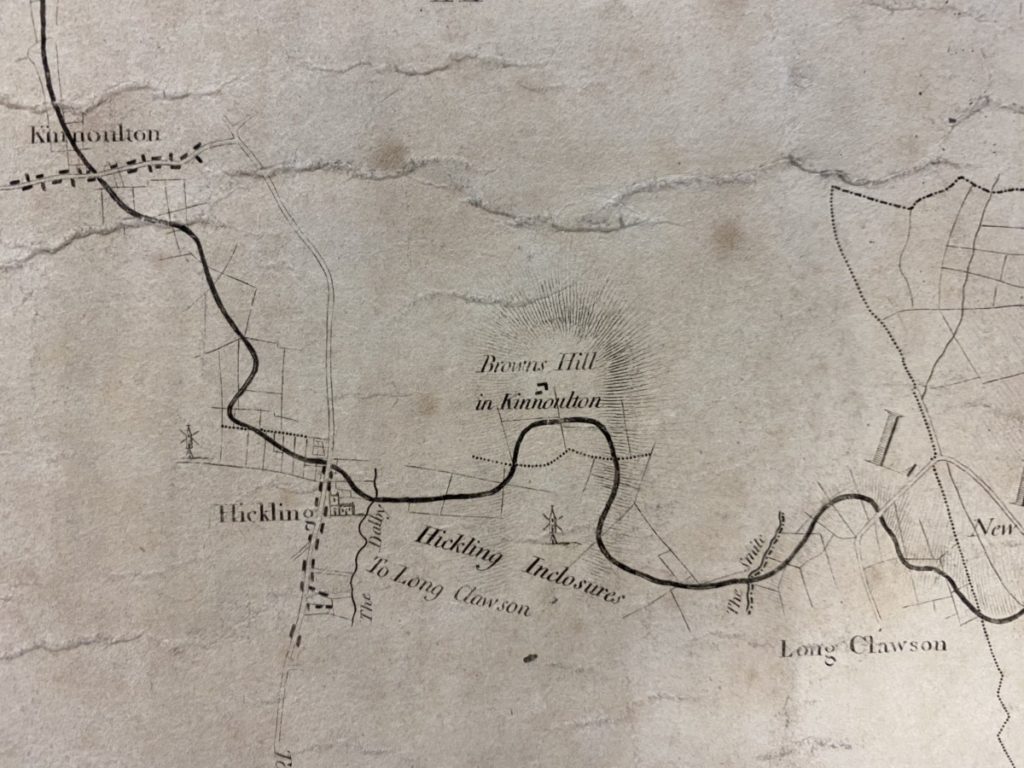

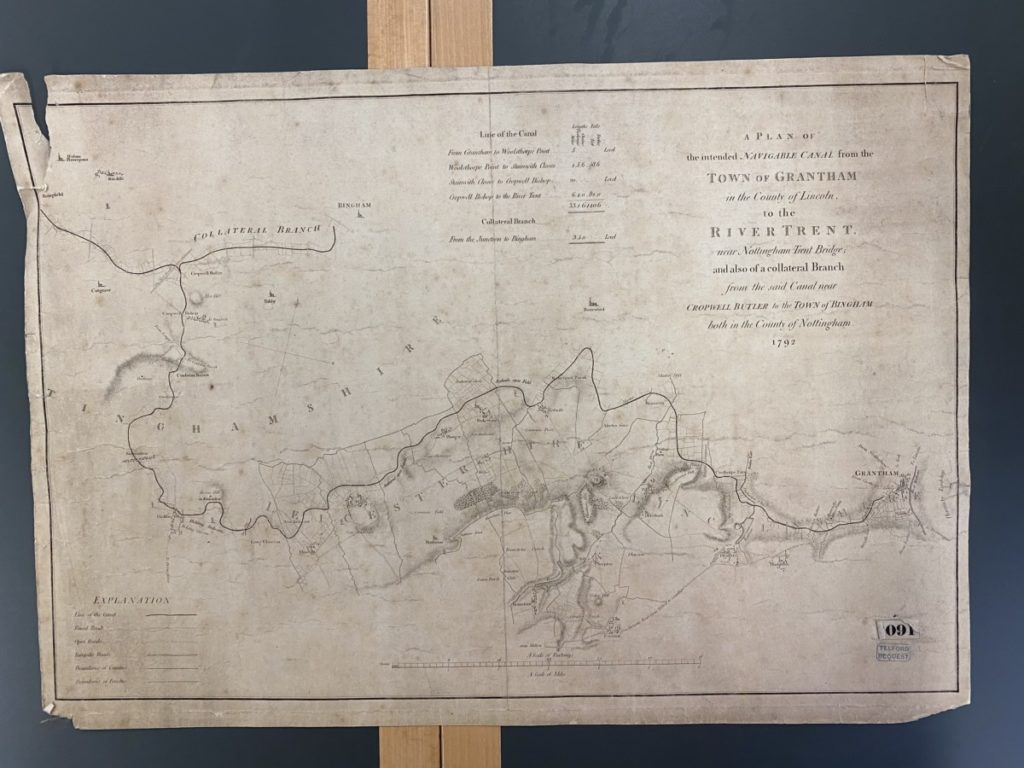

1792: (original map/plan held by Notts Archives)

A beautifully drawn plan of the proposed Grantham Canal is held in Notts Archives. It shows the route the canal was expected to take including important landscape features and buildings along its route. This plan may show the Plough Inn in Hickling but it isn’t entirely clear.

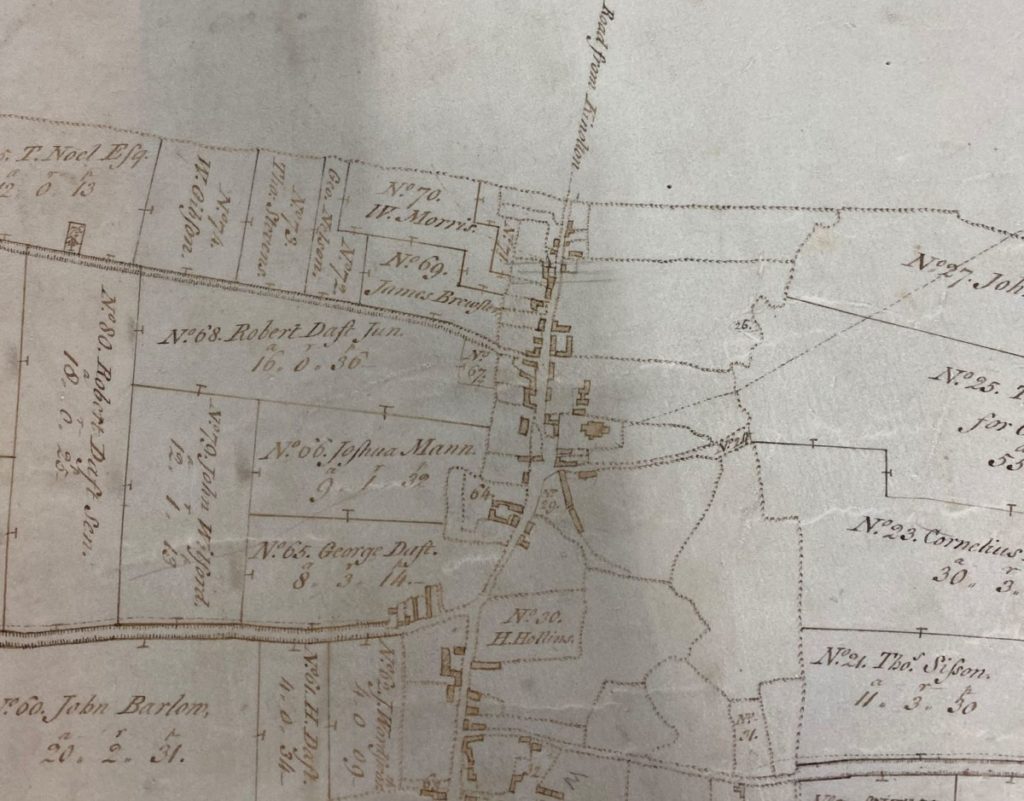

1793: (originals held by Notts Archives; work is ongoing)

Act of Parliament 1793; it is a substantial book and copies are held in a number of local archive offices. Most of the detail is functional but some sections give a fascinating insight into the processes and the values of the time:

- It details the route, the water sources and arrangements for acquiring the necessary land. It also deals with access to the canal once it opens for business, towpaths, bridges, repairs and impacts on other watercourses.

- Pages 6-7; details of ‘exceptions’ in Hickling giving details of ownership & businesses.

- “Provided always, and be it further enacted or be construed to extend, to authorise or impower the said Company of Proprietors, or any Person or Persons employed by them, to take or use, or to injure or damage any House or other Building, except a Messuage or Tenement now or late the Property of Thomas Burrows and in his own occupation, a Barn and Weaver’s Shop, now or late the Property of John Nelson, in the occupation of John Swift, a Messuage or Tenement and Outbuildings, now or late the Property of George Faulks, in the Occupation of Martha Morris, and another Messuage or Tenement and Outbuildings, now or late the Property of John Mann, in the Occupation of John Lock, all in the Parish of Hickling aforesaid, or to exercise any of the Powers hereby given, upon, through, or over any Land or Ground whatsoever, which, on the First Day of January, One thousand Seven hundred and Ninety-three, was a Garden, Yard, Park, Paddock, planted Walk, or Avenue to a House, or Lawn inclosed and adjoining to a Manor House, or through or over any Garden or Yard, without the consent of the Owners of the same respectively, other than the Gardens and Yards belonging to any Cottages or Tenements under the respective Yearly Value of Six Pounds.”

- This paragraph names those property owners who would lose land to the canal construction.

- Of note: those owning property below a yearly value of £6 have no rights over the taking of their land/property for the use of the canal company …

- Also, arrangements for Wharf buildings and weighing of cargo; provision of mooring and passing places.

- Penalties for various offences (including dropping rubbish).

- Some allowance is given to deviate up to 100 yards from the plans (plan detailed above but reference book not available in this collection – search ongoing)

- Specific paragraphs detail constraints for the Hickling stretch; the terms give precise detail of ownership and field names (pages 73-4).

- “And whereas it hath been agreed upon by and between the said Company of Proprietors, and the Reverend Robert Barker, Rector of Hickling aforesaid, and John Collishaw of the same Place, that the Line or Course of the said intended Canal, near the Town of Hickling aforesaid, shall be altered in the Manner hereinafter mentioned. Be it therefore further enacted, That instead of the Line or Course of the said Canal near the said Town of Hickling, specified and set forth in the said Map or Plan, and Book of Reference, the said Company of Proprietors shall cut and make the said Canal from the Dwelling House of Thomas Burrows, at Hickling aforesaid, in a direct Line through a Piece of Land called the Home Close, belonging to the said John Collishaw, and then to proceed along the North Side of certain Closes of the said Robert Barker, called Norbrook and Moory Wong, close to the Hedge or Fence which divides the said Close of the said Robert Barker called Moory Wong, from a Close of the said John Collishaw, called Kettle Wong, which the Line or Course of the said Canal, as now specified in the said Map or Plan, passes through.”

- Arrangements and rights for fishing and game.

- Arrangements for the reconveyance of land not used.

- Page 78 requires that markers should be placed every quarter mile; those surviving on the Hickling section are listed (English Heritage).

- And be it further enacted, That the said intended Canal and Collateral Cut shall be measured, and Stones or Posts erected on the Sides thereof respectively, at a Quarter of a Mile Distance from each other, and that all Goods, Wares, and Merchandise which are made liable to the several Rates and Duties hereby imposed, that shall be navigated, carried, or conveyed upon the said intended Canal and Collateral Cut, up to or part any of the Stones or Posts to be erected, shall be charged with and pay the said Rates and Duties for One Quarter of a Mile for every Stone they shall pass by, in proportion to the Rates hereinbefore granted.

- The original purpose of these waymarkers was to determine the distance travelled by canal users and how much they owed in ‘Rates and Duties’ – the canal was in private ownership with shareholders to satisfy and, like the railways, every journey had a price.

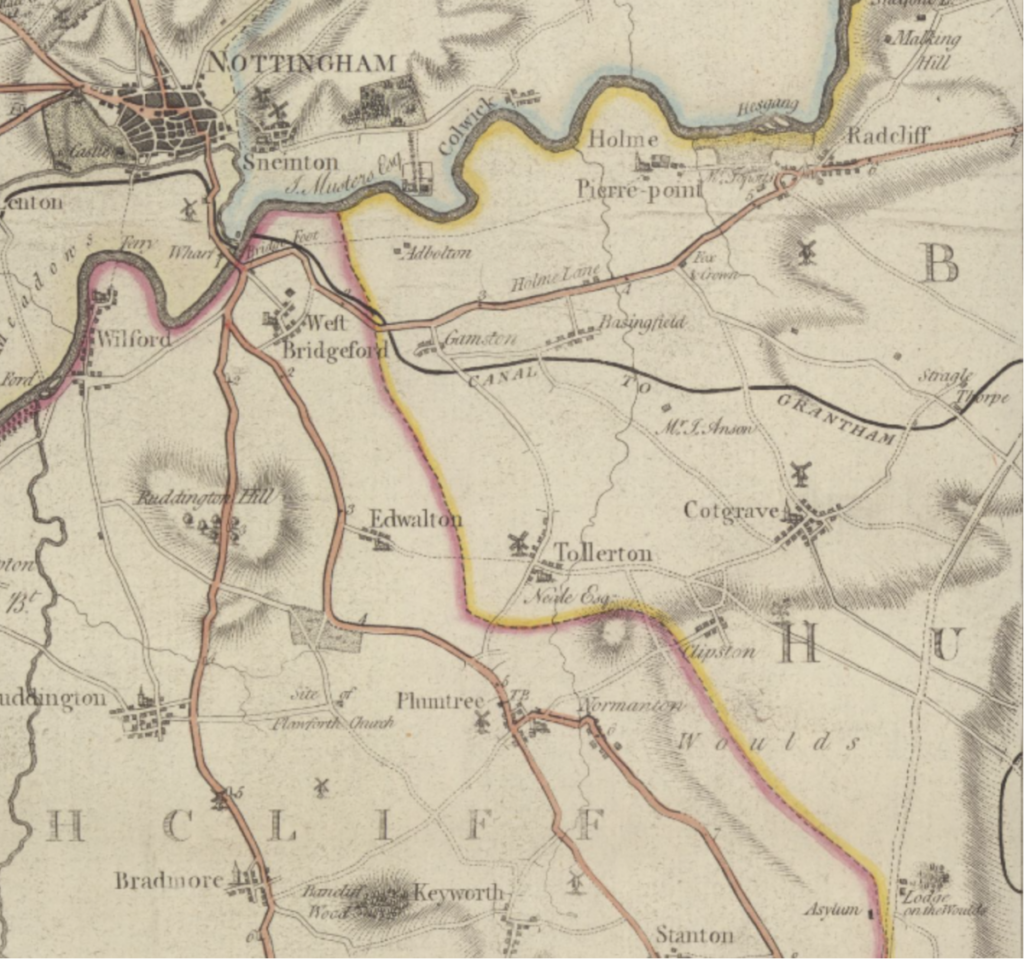

1794: Chapman’s Map of Nottinghamshire – an oddity

Bizarrely, the 1794 Chapman map of Nottinghamshire features a fully constructed Grantham Canal including the branch-line to Bingham which was never constructed. This seems to have been drawn from the plans accompanying the 1793 Act of Parliament but it was published 3 years before construction was completed.

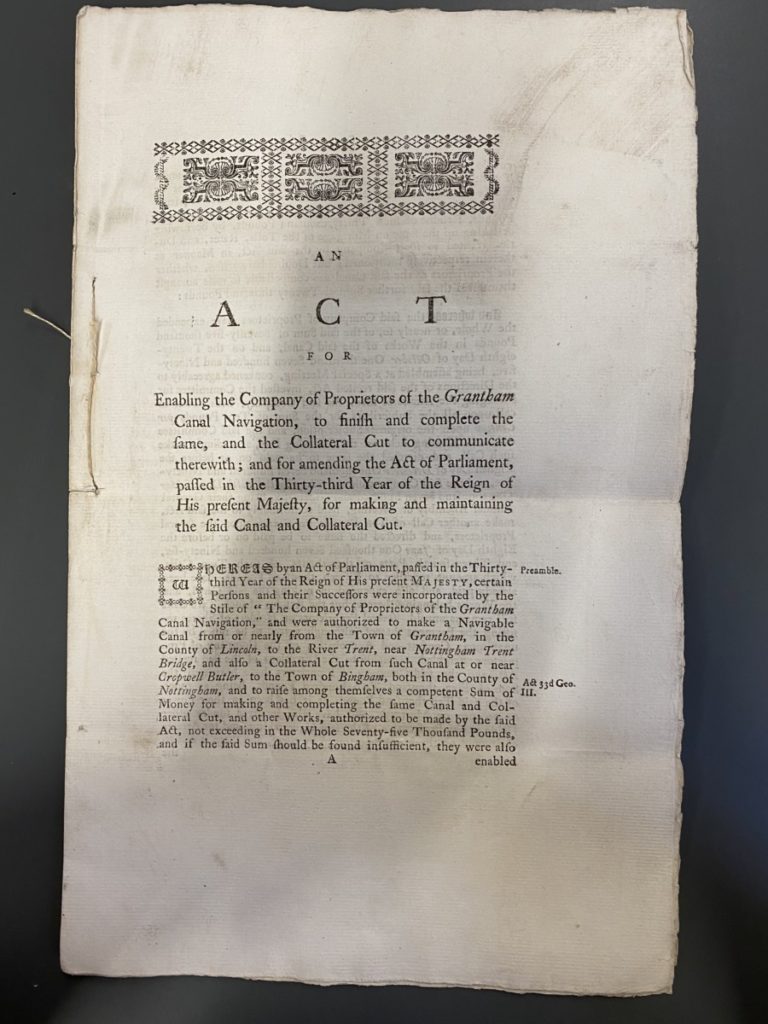

1797: Act of Parliament confirming the completion of the Grantham Canal (originals held by Notts Archives; work is ongoing)

A further Act of Parliament confirms the details for the construction & maintenance of the Grantham Canal. The document includes financing, shareholding & costs (at this point it has already cost £75,000).

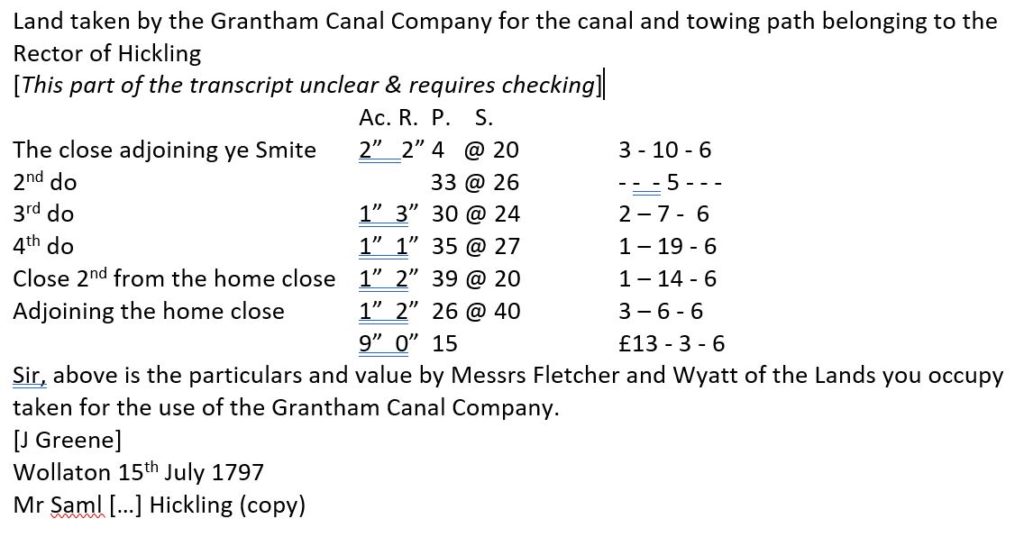

1797: (original document held by Notts Archives)

Acct of land taken by the Canal Company with an estimate of the site value by Messrs Fletcher and Wyatt.

1797: The first commercial journey on the Grantham Canal was from Hickling:

Histories of the canal (see bibliography) record that the Grantham Canal was built ‘cheaply’ and many of those involved came to it with little or no experience – this inevitably led to problems. Specifically, problems with the gypsum sections around Cropwell Bishop and Butler led to delays in the opening of the canal from the Nottingham end. However, in April 1797 the canal committee announced that; “Thomas Lockwood of Hickling be allowed the amount of tonnage which he paid for a boat of coals being the first navigated upon the canal to Grantham.” The whole canal was opened to traffic a few weeks later (by early summer).

The Working Years:

By 1806 debts had been repaid and shareholders began to see a return on their investments. Chris Cove-Smith writes that, “… the canal grew slowly to success in about 1820, reaching a peak in 1839 which it maintained until 1851 when the Nottingham to Grantham railway line was opened.” Having passed into the ownership of the railways, the future of the Grantham Canal became more and more uncertain:

- “Few railways encouraged trade upon canals, unless they acted as viable extensions to their lines. Obviously, the Grantham Canal, was in open competition, providing a cheaper, but slower, form of heavy transport.”

- “Trade steadily declined although reasonable tonnages were recorded until the early part of the twentieth century. The canal was also used for military purposes in the First World War when stores and men were transported from Nottingham to Grantham at the time of the occupation of Alma Park Camp by the Machine Gun Corps. By 1929, however, trade had almost ceased, the canal was in urgent need of maintenance and dredging and the successors of the GNR, the London & North Eastern Railway into which it had been absorbed in 1924, closed the waterway to traffic. It was legally ‘abandoned’ in 1936 under the London & North Eastern Railway (General Powers) Act of 1936, Section 38, but curiously fortunate for us today, the whole canal was maintained in water since agreements had been entered into for water extraction at various points for agricultural purposes.” (Chris Cove-Smith pp11-12)

1828: a mortgage document was signed by Joseph Daft in 1828 which details land split by the canal.

- (work ongoing; including transcription of this document and the schedule accompanying the Enclosure Map of 1774).

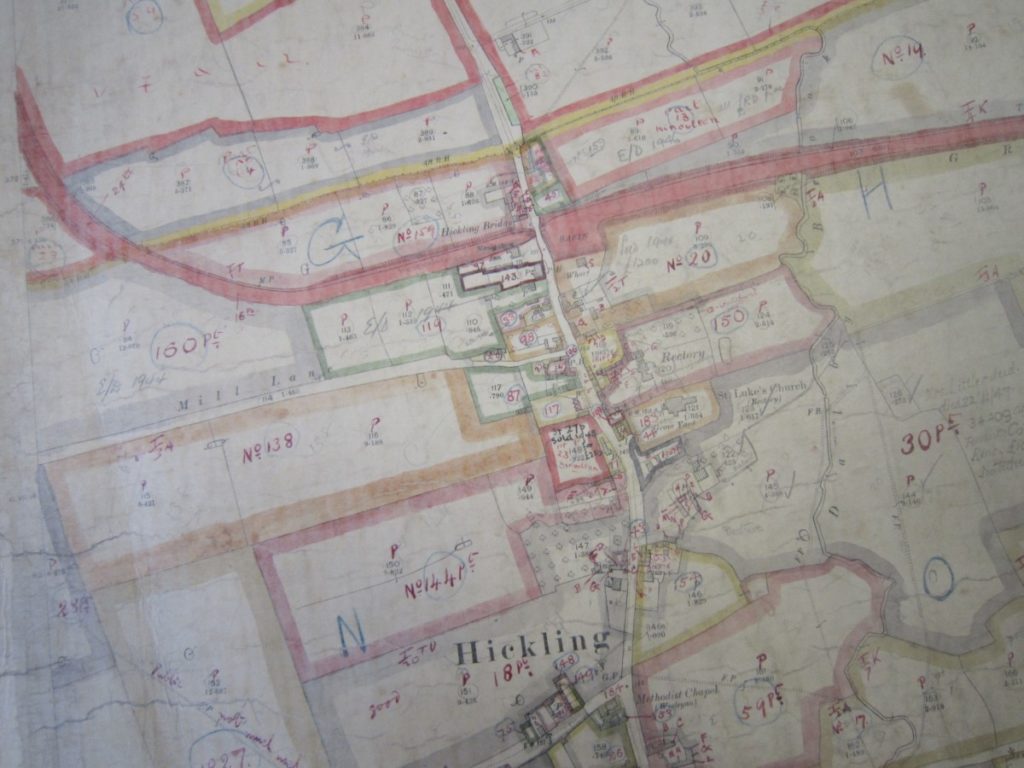

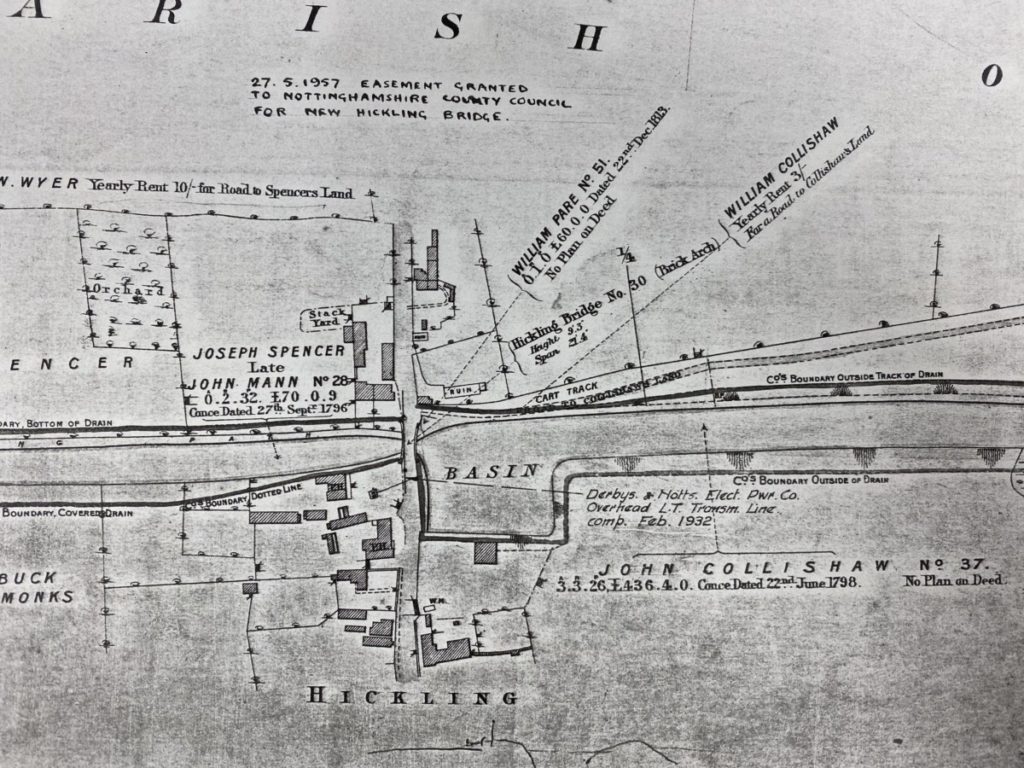

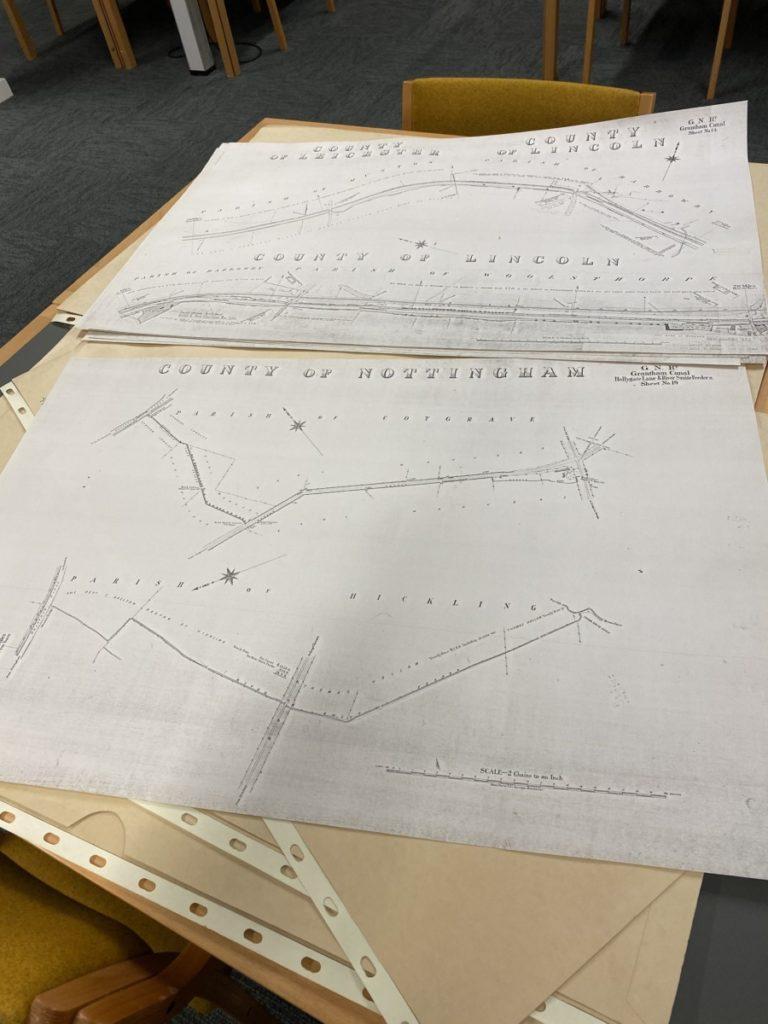

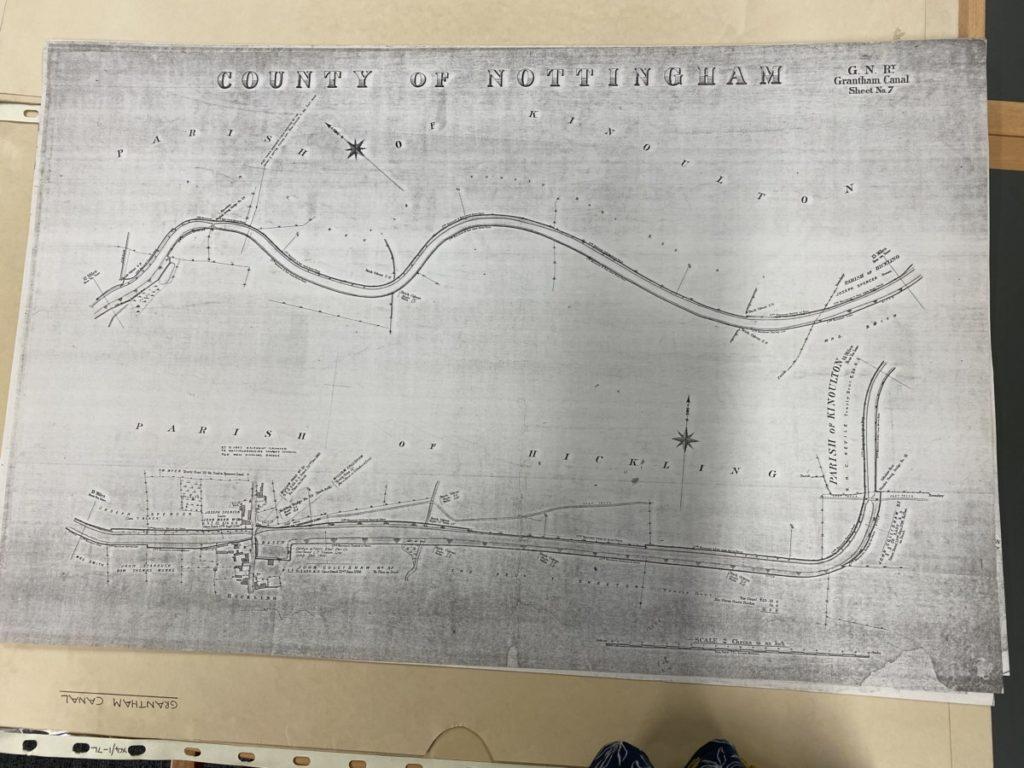

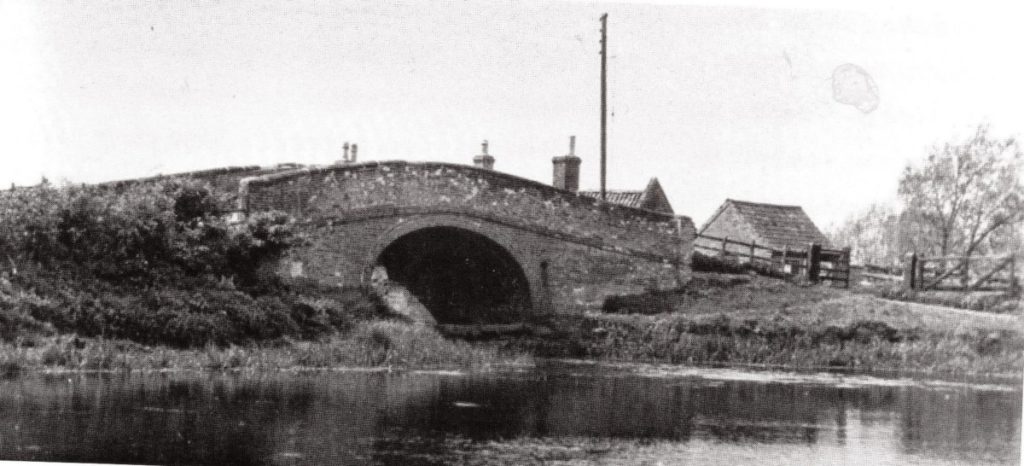

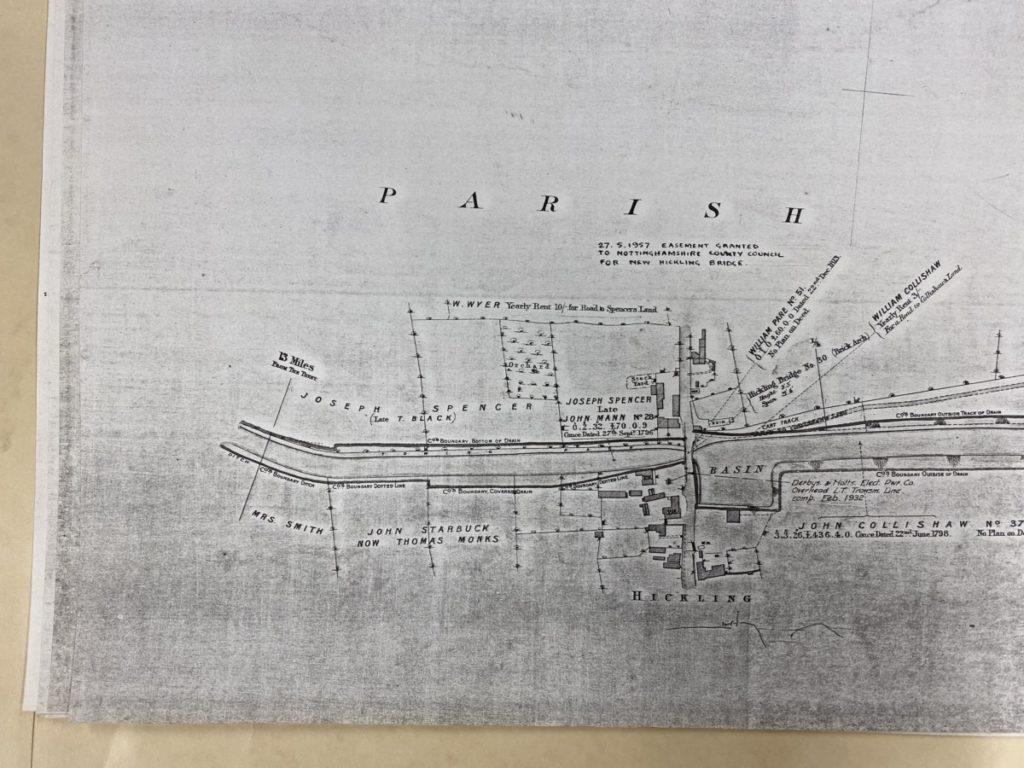

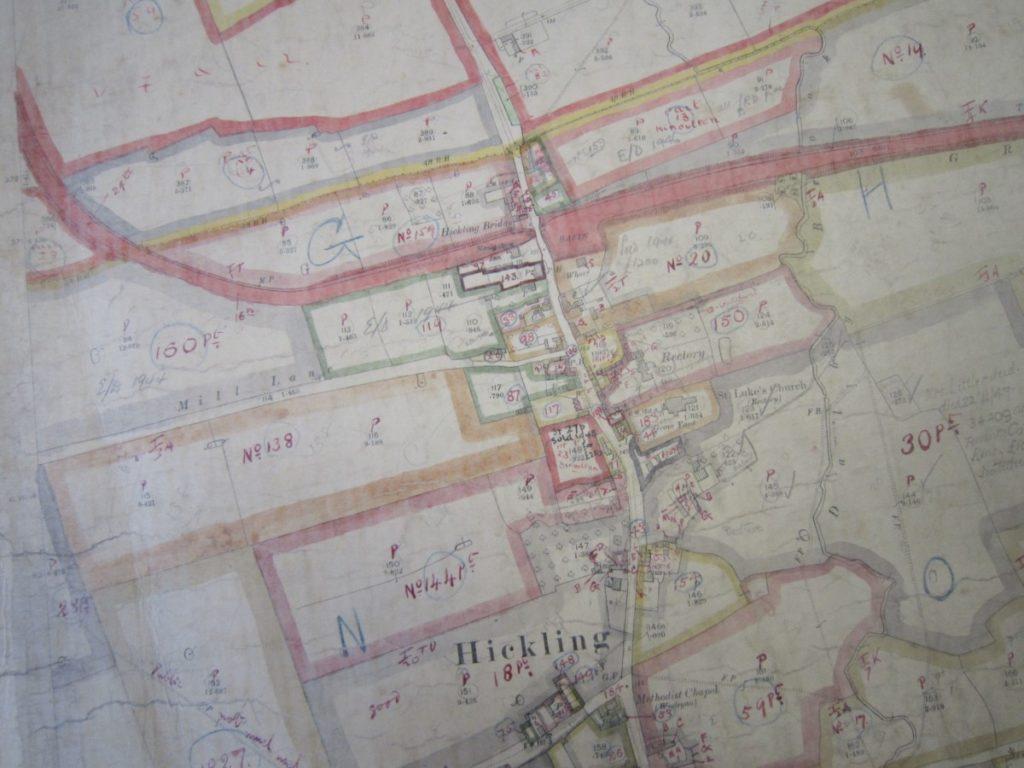

1900: In 1900 a full survey of the Grantham Canal was carried out including a beautiful set of A1-sized plans. The plans include boundaries, ownership and valuations. (original documents held by Notts Archives; transcription & research ongoing). It notes the dimensions of the Hickling canal bridge; height 9’3” and span 21’4”.

1910: Finance Act Map & Schedule (ledger); in 1910 assessments were made across the country of land ownership and values – the entries for the canal, Basin and Wharf in Hickling show:

- The land occupied by the Grantham Canal is occupied by the Canal Company and owned by the Great Northern Railway covering 20 acres and with an annual value of £45.

- The Wharf area is owned and occupied by William Collishaw; the area covers 5 acres and has an annual value of £15. The later sale of the property to JW Harriman has been overwritten at a later date.

Follow links for:

The Old Lady Bay Bridge connection to the River Trent

Hand-colourised postcards remain an amazing resource for local history studies; Brian Lund has collated a fascinating book of Nottinghamshire postcards from the early 1900s alongside photographs of how the area looks now. Included in his book is a postcard showing the old Lady Bay Bridge which marked the point the Grantham Canal connected with the Trent. This connection has long-since been blocked and filled in with little likelihood of it being restored as the main cabling for the City of Nottingham now runs through this route.

New life as a remainder waterway and wildlife haven:

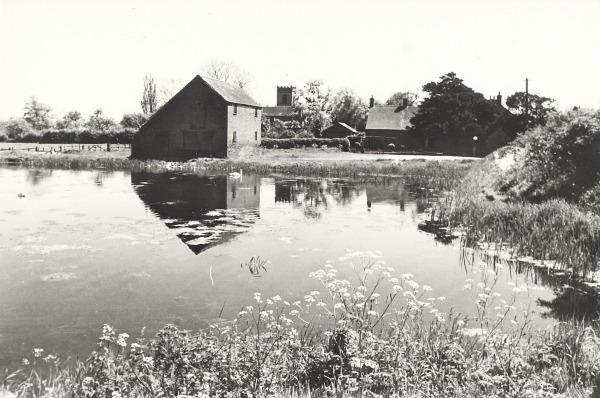

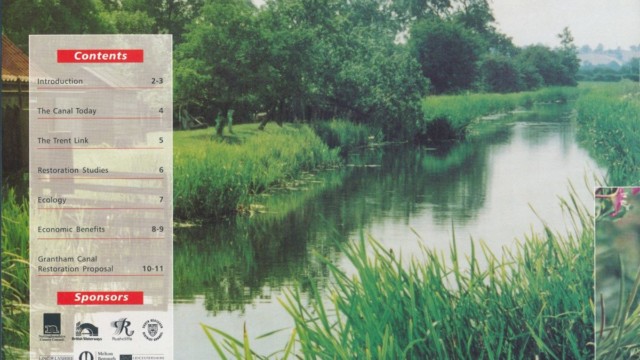

“Since the Grantham Canal closed to boating in 1929, nature has reclaimed it. It is still mostly full of water, and is a valuable wetland habitat, running through the arable landscape of the Vale of Belvoir.” (Canal & River Trust @July 2022)

In the past 100 years the canal has become a valuable wildlife corridor with areas of SSSIs and Local Wildlife Sites; swans were amongst the early colonists, in the 1930s they were rare visitors but for many decades they have been resident. Otters and water voles are recolonising and kingfishers are here but elusive! It is a wonderful experience to watch the swallows dipping and diving over the open waters of the canal and Basin in an early evening and equally wonderful to stay and watch the bats as they emerge at dusk, swooping to hunt for insects over the surface of the water. Even in the Hickling stretch there are several distinct habitat areas and in 2018 a community conservation group (working with the Canal & River Trust, Rushcliffe BC & the Notts Wildlife Trust) began work on surveying the mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, insects and plantlife of the canal and its surroundings.

Sadly, the Grantham Canal always struggled to be commercially viable; its most profitable years came in the early 1800s but water levels have been problematic throughout its existence (strong weed growth, the build-up of silt, the gypsum section around Cropwell Bishop & Cropwell Butler and (latterly) lack of use) making the route unreliable.

- The coming of the railways in the mid-1800s precipitated a slow decline in the commercial use of the canal and meant that its active years were relatively short; by the end of the 1800s, the canal was in severe decline and by the early-1920s its working life was over.

- By 1912 William (Wharf) Collishaw had retired and it seems that the Wharf business had closed by this date. In 1921 the area was bought by Mr JW Harriman and in 1941 the Wharf House and Wharf Building was sold to Mr Douglas Booth – in the 1950s the east wall fell down and was rebuilt in block work. In 1995, following the English Heritage listing of the building, the owners were required to undergo restoration work to make the building water tight – English Heritage gave a grant of £3,232 to cover 25% of the cost. In 2014 the building was re-pointed with lime mortar.

- The traditional curtilage was split up in 1963 when the Wharf House and the rest of the site was sold to Mr & Mrs AE Faulks with the wharf building itself remaining in the ownership of the Booth family; however, the Faulks family looked after the site on behalf of the owners, managing it day-to-day and for village events for over 50 years.

- From these early years of the 1900s, records show that the Wharf Yard was regularly used as a community space; for Fairs, Festivals and Karnivals as well as celebrations for the Coronation, outdoor services and Bonfire Night – Grantham Canal – from the Wadkin Archives (link).

- In approx. 2014, in agreement with the Parish Council and local councillors, the grassed area around the building was planted with wildflowers.

- 1922: The 1910 Finance Act illustrates the traditional canal land ownership pattern whereby the canal owners (then the Great Northern Railway and now the Canal & River Trust) own the canal itself, the towpath and up to & including the towpath boundary plus a metre from the water’s edge on the non-towpath side. Full details are unknown but it appears that a conveyance in 1922 involving William (Wharf?) Collishaw and James Wright Collishaw (& possibly also involving Percy Collishaw) changed this when ownership up to the water’s edge on the towpath side was conveyed to the farming landowner of much of the Hickling stretch.

- The foresight that lay behind these transactions may be the reason that the Grantham canal is still ‘in water’. It is likely that this agreement involved rights of access to the canal for agricultural purposes at a time when the canal was in serious decline and was in danger of being allowed to dry up when maintenance stopped.

- Securing these agricultural rights for the farmer bordering parts of the Hickling section of the canal in 1922, may be the reason why the 1936 Act of Parliament (below) included clauses requiring maintenance of a water depth of 2ft for agricultural purposes along the full length of the canal.

- By 1924: a photograph of children from the Squires and Wiles family taken in the yard of the Wharf Building in 1924 shows that the area has already grassed over by this time and the building is showing signs of deteriorating.

Closure to Boats & Beyond:

- In 1936 an Act of Parliament formally closed the canal to boats (there had been no traffic on it for the previous 7 years). This had two major effects:

- Financial responsibilities were massively reduced because ongoing maintenance requirements were minimised;

- But also, the waterway was to be deliberately allowed to evolve as a wildlife corridor and for the quiet enjoyment of visitors. Some stretches have been designated as SSSIs and the Hickling stretch is designated as a local wildlife site.

- (the Act also stated that water should be kept to a depth of 2 feet and could be used for agricultural purposes (irrigation and drinking water for animals))

- The Transport Act of 1968 categorised the Grantham Canal as a ‘remainder waterway’ with no economic future. In 1969 proposals were made to close and infill most of the canal:

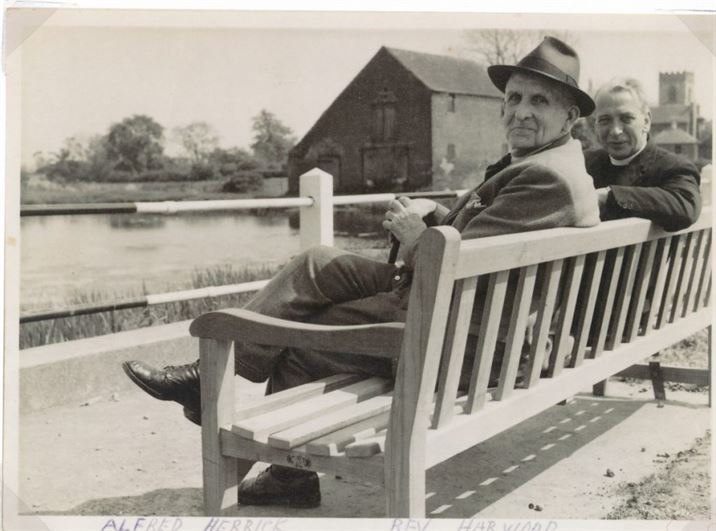

- “The proposal to close and infill most of the canal was strongly contested by the “Grantham Civic Trust” and the Grantham Angling Association. Ultimately, with the support of the Inland Waterways Association and the MP for Carlton, Mr Phillip Holland, the canal was saved. The Grantham Canal Society was then formed, later to be called the Grantham Canal Restoration Society.” (The Grantham Canal: Meander p.28)

- And so the Grantham Canal Restoration Society (now the Grantham Canal Society) came into existence – continuing to carry out its invaluable volunteer work 50 years later.

Margaret Wadkin: press clippings – history & closure of the canal

1943: Dredging just west of Canal Farm, Hickling

(with thanks to the GCS & John Keays)

“LNER (London & North Eastern Railway) on the cabin side indicates the canal’s ownership at this time. Maintenance work was still going on, despite the canal having been closed by Act of Parliament seven years earlier. The 1936 closure Act stipulated that two feet of water be maintained in the canal ‘for agricultural purposes’. This stipulation was fortuitous. It prevented the canal from being obliterated from the landscape; until the 1968 Transport Act took away this important stipulation. The canal was now under serious threat of extinction, with one local authority already having eyes on it for landfill. The Grantham Canal Society was formed in the following year. These photographs first appeared in Waterfront News 2002. They were sent in by John Keays, taken in March 1943 by his father on a folding Kodak 120 camera. The location just west of Canal Farm, Hickling.” (posted by GCS November 2022)

1971, 1977 & 1997 – canal rallies held at the Wharf:

1994 (onwards): In 1994 grant funding was sourced to dredge the Hickling stretch of the canal, to renovate Clarke’s Bridge and the swing bridges and to landscape and secure the banks of the Basin and Wharf areas. It was at this time and over the following 5 or 6 years that the paving was renovated, bollards and the slipway were installed and the towpath was gravelled heading east (the western section was done later and was still grassed in 2000); locally, the area even became known as ‘the Queen Mary Wharf’ for a while. The new towpath surface saw the end of old by-laws prohibiting cycling and the canal has developed into a popular new cycle route. In time, the bollards along the road were removed, the towpath bedded in and the slipway area grassed over again. These were big changes which took a little getting used to but time has brought familiarity and affection.

1994 Restoration – Grantham Navigation memories (GCS FBk post)

1994 Restoration – A Neighbour’s Collection (documents, leaflets, brochures & news articles):

1994: Notes from a meeting of the Nottinghamshire Building Preservation Trust in March 1994 outlined discussions about the future of the Wharf Building (KCRdocs):

- Proposal for the building to be used as a Field Study Centre and an HQ for the Canal Trust & GCRS. Funding totalling c.£12,000 is available and the owner is reported to be willing to turn down a larger offer if the building could be used for this purpose. Even so, it seems that the funding couldn’t be raised and no agreement followed.

- Possible loan from the Architectural Heritage Fund to the GCRS to purchase the building.

- Proposal to purchase follows a failed planning application and a failed planning appeal to convert the building to residential use and English Heritage Listing. The owner is recorded, in consequence, to be unable/unwilling to maintain the building.

- It is noted that the site is an ‘open space’ in the Local Plan.

1995: Grantham Canal Restoration Society proposals – 22nd September 1995.

Gallery of the changes from 1996-2000:

2000: Grantham Canal Draft Strategy published & Hickling PC response.

In the end, the draft strategy didn’t proceed beyond the consultation stages; it did cause consternation, though; it identified Hickling as a ‘primary access node’ with excited discussions and images of a visitor centre and car parking at a public meeting held in Kinoulton Village Hall (pdf of draft consultation plan).

What’s Next?

The work of volunteers and the support of the Canal & River Trust and the Notts Wildlife Trust is ensuring that the Grantham Canal (& the Hickling stretch) have a future – even though ‘times-are-a-changin’. The Grantham Canal Society works incredibly hard on maintaining the canal and their focus on wildlife and everyday enjoyment of this wonderful waterway represents the continuation of over 50 years of work – we are all very grateful.

Nevertheless, It is fair to say that since the 1980s frustrations have rumbled in the village; particularly, worries about the village community not being included in the early stages of plans affecting the village and worries about losing its rural & farming heritage to tourist-based initiatives.

- These ups and downs are too recent to be included here (& no one wants to get involved in the ‘nimby’ debate!) but in 2008 the Parish Council in Hickling was behind the formation of a group which invited representatives from the parishes along the Grantham Canal and representatives of the various canal organisations to get to know each other and to discuss plans and concerns – the Grantham Canal Community Liaison Group (GCCLG).

- Sadly, this initiative didn’t last very long but the principle behind such open discussions and the protection of the Hickling Conservation Area remains important to people in Hickling and continues in the newly adopted Hickling & Hickling Pastures Neighbourhood Plan (March 2022).

In 2015 the lease of the Old Wharf was sold and permission given to open The Old Wharf Tearooms:

- “Change of use to cafe/tea rooms and bike hire/repairs, and construction of new toilet block. The Old Wharf Building Main Street Hickling Nottinghamshire.”

Community Table Tennis Table:

In 2017 the owners of the tearooms business kindly allowed the Hickling Table Tennis Club to install an outdoor table tennis table for the use of the community. Organised by Eric Wood and Jog Chahal and with generous grants from Councillors John Cottee and Tina Combellack the table has been a great success. The table tennis club have provided free bats and balls which are available from the tearooms.

In 2018 a community conservation group (working with the Canal & River Trust, Rushcliffe BC & the Notts Wildlife Trust) began work on surveying the mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, insects and plantlife of the canal and its surroundings in the hope that a Local Nature Reserve (LNR) designation can be applied to the Hickling section of the canal.

A community space enjoyed by visitors:

Margaret Wadkin collected news clippings over several decades and for much of this time she was the contributor for Hickling news, too; sadly, several of her albums are now missing but this gallery details some of the people, escapades (including a young farmers’ hovercraft …), bank holiday visitors and brawling travellers in need of rescue as well as Karnivals and Bonfire Nights in the Wharf Yard – not to mention frogs & hailstones in July!

Bibliography:

- The Grantham Canal: early days (a detailed history of the first 25 years) by R Philpotts (1976 & 1978) – pdf

- The Grantham Canal: meander through the beautiful Vale of Belvoir (published by the Grantham Canal Society 2014)

- The Grantham Canal Today: a brief history and guide by Chris Cove-Smith (1974) – pdf

- The Romantic Canal: alongside the Grantham by Hugh Marrows and published by the Grantham Canal Partnership (2003)

A Short History of the Grantham Canal

(by Carol Beadle – undated)

Initially there was a lot of opposition to the building of a canal linking Nottingham to Grantham. Eventually, work on the project started in the summer of 1793. The link between Grantham and Hickling was the responsibiiity of the engineer, William King and it took 4 years to build. The canal was opened for navigation in 1797 and it was 33 miles long with l8 locks and 67 bridges of either red brick or wood. Mile for mile, this canal was the second cheapest built at that time:

- Each lock cost about £950

- The brick bridges about £120 each

- Unskilled labourers were paid 2/- aday (l0p)

- Skilled and craftsmen were paid 3/- a day (15p)

The Grantham Canal made a significant contribution to the commercial development of Grantham Town and the surrounding Vale of Belvoir. When the Canal was opened, coal prices in the area dropped almost immediately, by 1/- a ton. It took 2 days for the barges to get from Trent Lock to Grantham. Dung, night soil, marl and ashes were carried toll-free. The coal, stone, timber, grain, malt, meat, flour and lime paid 2½d per ton toll at Trent Lock.

The canal at Hickling goes into a basin which is 13.21 miles from the Trent. Hickling has winding hole No l0 – a winding hole is a considerably widened Canal section where there is space to enable the long narrow boats to turn around once their consignment had been delivered.

Here in Hickling is the original wharf and a listed C18th Century warehouse. During the heyday of the Canal (1801-1845) Hickling Basin was a major centre for reciprocal distribution of goods coming from Nottingham and Grantham, passing throughout the Vale of Belvoir. Since Hickling at this time was such an important centre it was able to support 4 hostelries.

ln the 1850’s the coming of the railway caused a decline in the businesses using the canals. There was a temporary reprieve during World War I when the Army used the canal to transport equipment and munitions around the area. By 1929 commercial traffic ceased and the canal was closed. From l95l housing and road development removed sections of the canal.

Today the Grantham Canal Partnership work on various projects to clear the canal and their efforts have cleared 2½ miles at Hickling. British Waterways has carried out considerable restoration work on the basin including the piling of the wharf banks allied to extensive dredging which created 1 mile of broad cruiseway. Along the towpath towards Hose, hidden amongst the bushes is an original wooden hut with a small fireplace for the lengthman – this is in need of restoration.

The bridge at Hickling is No 30 along the route. This bridge used to be a ‘hump’ bridge but now has been significantly lowered so that traffic travelling through Hickling can be unaware they are going over the canal . Hickling Basin is a haven for a multitude of swans and wildfowl. The Canal is an excellent habitat for several species of fish, mainly tench, perch, bream, pike and carp.