Avril (Winks) Thesing – evacuated to Field Farm, Hickling Pastures

“a small contribution to the legacy of those dear people who rose to our aid”

Picking up a page from our website about William Salt who died during WWI, Avril contacted us to share her memories of the Salt family, her evacuation to Field Farm and a friendship which has continued for over 75 years.

Avril was evacuated from London with her mother; her father was on active service. As a frightened 3-year old she arrived at Field Farm having endured bombing in London and an awful first attempt to find safety in Doncaster (they found themselves next door to a brothel and had to barricade their door from the inside at night). Field Farm became Avril’s ‘first home’ and the kindness of Albert and Mary Salt and their son, John, offered a haven which she has never forgotten.

At the end of the war, Avril’s father thankfully returned and the family (including her two sisters, born after the war) visited Field Farm for their summer holidays and Mary visited them in London. In 1958 the family moved to New Zealand, in search of a fresh start. Avril returned to Hickling with her husband on their honeymoon and once more for the 50th anniversary of the end of the war.

Avril has written her memories down so that they can be read by her grandchildren and we are incredibly grateful to her for offering to share her writings with us, too. The old farmhouse, the orchards, visits to Melton Market, milking, cheese-making, knitting circles, Bill in the shafts of the family trap, leghorn chickens roosting in the apple trees, problems with 3-legged stools; Avril’s writing is wonderfully descriptive, gently kind and full of understanding. These pages give us an extraordinary view into wartime England and an almost lost part of our village history – enjoy!

Avril closes her story with these words: “Field Farm, Hickling Pastures has a lifelong place of great affection in my heart. It is where my mother and I found refuge in the desperation of wartime, that blossomed into ongoing friendship between our family and the Salts. Whilst many sacrifices are made in a time of war, gratitude must be given for the way the people of the Midlands of England opened their homes and hearts to traumatised Londoners such as us, for an indeterminant period. Whilst not all these connections were successful, they cannot take from many that were, to the degree that we were rewarded by the benefits of mutual friendship that richly coloured our lives and lasted a lifetime.”

FIELD FARM HICKLING PASTURES: A wartime experience

By Avril (Winks) Thesing (2022)

Arrival at Field Farm

Field Farm, Hickling Pastures was where my mother and I were evacuated during the latter part of World War 2. As a 3 year old I experienced it as my first home, where I was awoken to the world, learned about family and began to grow up. My mother and I had initially come there after traumatic air raids in London, closely followed by an unhappy sojourn in Doncaster. My mother was always in correspondence with relatives who were already evacuees in Nottingham. It was through Gladys Fairholm, the kind person who sheltered them that my mother and I came to know the Albert Salt family who we lived with at Field Farm for the rest of the war. The year was around 1944-45. To my mother, Devina (Dill) Winks after her earlier war experiences it must have felt like paradise, although we could not know then how significant this meeting would be for our family.

We were first greeted at Melton Mowbray Station by Mary Salt in the trap, with Bill in the shafts. As a toddler I no doubt slept as we jogged along the Melton roads after the train journey, or stared around me at the novelty of endless farmland. Meanwhile, as we turned off Melton Road and began to jolt over the neighbouring fields between opening and closing gates, my mother and Mary Salt’s private thoughts must have been well occupied as to how we were going to live together for an indeterminant period.

Whilst I had never yet ridden in a horse and cart, even in London the one-horse vehicle was by no means a strange experience. Trades people used only carts, as few private people had cars. Horse troughs, placed strategically, were a familiar sight in London streets. In any case with wartime restrictions prioritising fuel for defence purposes, those who did own mechanical vehicles mostly had them up on blocks in their sheds awaiting an unseeable future.

My earliest memories of Field Farm are of Mary Salt sitting in that cart, reins in hand against a background of dark waving trees, but probably my infancy at the time prevents my recall of the actual first meeting with the Salt family: Albert Davies Salt, Mary Oxby Salt and son John Richard Salt. However, on subsequent occasions, arrival was always heralded by the ringing sound of either the men’s hobnail boots, or the horses’ shoes on the cobbles of the yard. At the time I first met the Salts they were farming alone with their son John Salt, who was a young man in his early 30s (of similar years to my parents) and was undertaking much of the heavier work on the farm.

The farmhouse itself was comfortably enclosed from the weather by stables, a barn, and a cowshed. The entrance to the house was through a huge wooden door. This opened into an all-purpose room with a centrally drained stone floor and most intriguing for me, there was a colossal stone sink with a huge iron pump handle that swung up overhead. It was the only source of water for the household. I had never seen anything like it and in subsequent years privately measured my growth to adulthood by the ability to raise the weighty pump handle enough to obtain a trickle of water.

Following my experience of an incendiary bomb hit on our house in London, any unexpected noise or dark place was instantly alarming. So, it was unsurprising my earliest memories were how scary the farmhouse was with its dense stone walls, with no electric lights to open the gloom, particularly when accompanied by rain thundering on the tin roof of the kitchen. However, I came to know these first impressions were quickly dispelled at the end of the passageway further into the heart of the home, where a sense of warmth and deep security prevailed.

This hallway in the Salt farmhouse opened into the main living room that was dominated by a huge family table and sundry seating, with windows that looked out prettily onto the farmhouse garden. In what was to us refugees the “colder north,” the amazing all-purpose stove kept this room toasty warm. Apart from tending to our comfort it also allowed Mary Salt to repeatedly turn out the tastiest meals and to my delight its warming cupboard was sometimes even alive with the cheeping of small chicks incubating. Albert and Mary Salt had a small simple radio in the living room to which we would gravitate for the evening bulletin about the state of the war. It was our only communication with the war-torn world, apart from the very occasional censored letters, or local rumour. I recall that the radio was still in use in 1963 when I returned to the farm with my new husband on honeymoon.

As evacuees, familiarity with the Salt family and the farm soon meant that our fears were at least lulled with regard to the constant nightly bombardment we had been used to in London. No sirens wailed in the night, no searchlights pierced the clouds, no blackout had to be mandated. There was no hasty searching for gas masks (mine shaped like an elephant’s head with floppy ears) and dropping everything in order to run to the closest shelter. Although, nothing could allay my mother’s ever-present concerns about her husband’s whereabouts and even whether he would eventually come home.

Field Farm during wartime

I soon came to realise that the huge wooden table that dominated the living room at Field Farm was pivotal in our lives for performance of a myriad of daily household tasks. But, mostly of course it was a place for the family to gather for meals. The regularity of these was always dictated by the routines of the men’s work, notably the rhythm of the cows’ needs…The farmers must have had a drink before they went out into the mists of early morning for milking, but I only remember them taking a leisurely brunch later. This was followed around 4.00pm with afternoon tea, a meal with bread and jam and fruit cake. After this, the farmers would rise and again head off to work on whatever pressing problem faced them outdoors, until in late afternoon they routinely herded the cows to the shed. The only variation in these rituals was recognition of the Sunday as a day of rest. As a child aching for activity, I found the wait interminable whilst the farmers rested after lunch until forced by the approach of evening to milk the herd. Unable to tell the time, I would sit on the floor beside the couch where John Salt was asleep until at last, I could accompany him to the cowshed.

Expectedly, one of the first things my mother and I noticed upon our arrival at Field Farm was the reliance on candles and oil lamps because of the absence of electricity. Every night after the cattle were secured and the dogs fed, the farmers would come in and take some time for themselves before supper. As the daylight receded it was usual for Albert Salt to lift the big oil lamp from the sideboard onto the table. This was immediately a signal for me to gravitate there also and watch in fascination as he conjured up a flame, dispelling the dark with a rich warm golden glow, just by turning up the wick. But this action was only preparatory to Albert’s routine of shaving, for which he then assembled his equipment in careful order on the table. Never as yet having met my father, I knew nothing about such processes and would sit riveted in anticipation of Uncle Albert foaming up his beard and wielding his strop razor. Albert Davies Salt (born 26th August, 1884, died 1951) was by nature a quiet, gentle man, who smiled often but rarely spoke. Of medium height and strong he worked very hard as a farmer. He was always kind to us evacuees and accepting of us disrupting his home life, particularly as I was but a small child.

Once Albert had finished shaving this was the signal for his wife and my mother to lay the table for supper, and what a banquet it seemed. Of course, it was for 5 people in a physically demanding working household that diligently provided most of the produce they ate. There was freshly made bread and butter, fruit cake, ham, Stilton and other cheeses, as well as Melton Mowbray pies and copious cups of tea and creamy milk. Even to me as a small child it seemed a bounty after the ration books that dictated what my mother scrabbled together in meagre portions on two small plates at our kitchen table in London. I recall this well, because as my father was a soldier, on our return to London we were entitled to an American food parcel from which we were able to sample the miracles of dried egg powder and dried bananas.

Very soon living at Field Farm as evacuees became a comfortable routine. My mother and Auntie Mary gradually became great companions and would spend hours perfecting pastry for Melton pies in a small room next to the pump. I would often find them there working and chatting after my afternoon nap. I recall it was frequently an unnerving experience, for as I reached up to turn the door knob I would inevitably disturb a bunch of dead rabbits hanging on the back of the door, being John Salt’s most recent contribution to our larder. Of course, without electricity there was no refrigeration and foods had to be quickly processed. Much store was placed on the use of cool places in the farmhouse such as “the dairy,” with its stone walls, small window and ample air circulation. The atmosphere of the room fascinated me. I would often go there when on my daily rounds of the places on the farm I enjoyed most. I knew I must never touch, but would stand on tiptoe at the table in the centre of the room and just gaze into the big flowery jugs filled to the brim with the creamy milk straight from the cow.

The absence of tapped water as well as electric power meant all farm activities were reliant on retrieving water from the pump and heating kettles on the stove. This was true for my once a week bath-time, that prompted a flurry of activity in the second living room in the farm. As it had a distinctly colder aspect it first had to be well heated with an open fire. Then once this was blazing warmly a tin bath was placed before it on one of Mary Salt’s intricately made rag rugs. I would then climb into the modest amount of water, achieved with large jugs of cold water from the pump, topped up with kettles full of hot water frpm the stove.

This same room also became a refuge for me as a play room when Auntie Mary had her “knitting parties.” These were held in the main room and were a useful and eagerly anticipated part of the war effort where the country women around Hickling met together and knitted warm socks, blanket squares and other comforts to send to our soldiers. The knitting party was always attended by my mother and Nancy Sharp (Mary’s niece) and I recall a number of local women also converged on the farm for these sessions. Apart from the knitting itself the gatherings were no doubt an important factor in social exchange and support, that for a short time dispelled the women’s anxieties and isolation. As well the knitters were always treated to Auntie Mary’s delectable baking (and I probably made a few trips to the table there myself!) But for the rest, I would enjoy an otherwise uninterrupted morning with my favourite occupation setting out my huge collection of lead farm animals on a table in the other room.

I cannot say the lack of electricity at Field Farm really worried me as it was all I had ever really known. At my bedtime Mum would light a candle from the selection on the sideboard and the warmth of the farmhouse would follow us upstairs accompanied by flickering long shadows on the walls. Upon entering my bedroom there was always an element of surprise and intrigue as the floor sloped so steeply that if you forgot you could stumble. On really cold nights I would find Auntie Mary had put a stoneware bed warmer under my blankets, filled with hot water and closed with a stone cap. If I pushed my feet down too hard an encounter with the stone could be painful, as well as very hot, so it was always wrapped in a towel. As I was terrified of the dark for many years during and after the war I can only imagine my mother rested beside me patiently singing from her repertoire of wartime songs, until I succumbed to sleep after which she would retrieve the candle and return below.

Another nod to the absence of power and plumbed water was a wash stand (one of which stood in each bedroom) where a floral ewer always stood in its basin. As it was such an inconvenience to organise hot water, I became quite used to dragging a cold wet flannel over my face for a chilly morning wash. I was usually too focused on anticipation of the delights of the day’s activities to notice much discomfort. Given the weekly bath my mother would give me an occasional warm wash that included washing my neck and behind my ears. Distance from the toilet facilities also meant that there was a ceramic potty under the bed for night time use. This was something I was already used to in London where it was not safe to leave our Anderson shelter in which we slept at night. At Field Farm during the war years, as well as for a while afterwards until plumbing arrived, the Field Farm toilet was housed in a spacious long drop shed out in the yard. It was at the end of its own pathway, making finding it on a moonless night not too arduous. However, when I was long delayed in the facility during daytime my mother would become concerned, only to find that I had become engrossed with “reading” pictures in the Farmers’ Weekly that had been cut into convenient squares and tied onto a length of string to serve as toilet paper.

As well as my own there were 2 or 3 other bedrooms upstairs in the farmhouse including the “Apple room” where the apple harvest was stored annually. I recall the heavy autumn scent of storage still lingered in later years when Auntie Mary and I shared a bed there on one of our family holidays.

Outdoor pursuits at Field Farm

As the war churned on and I grew older, I became increasingly keen to explore the exciting world outside the farmhouse. In the absence of a father, I particularly attached myself to John Salt who was endlessly kind, funny and long suffering of a pre-schooler. The men were always busy and eventually, most days after the obligatory nap I was bundled up warmly and allowed to locate them at work out in the farm yard. Whilst I felt “free as a bird” I imagine there was some tacit arrangement as to who was “minding me.” It was obviously Uncle John, when I found my way to the cowshed after the daily nap. Albert and John Salt would be there crouched over on their three-legged stools. They each wore some ancient old flat caps on their heads whilst pressed to the warm furry flank of one or another of the cows. The caps were kept on individual hooks in the cowshed strictly for that purpose alone.

Uncle John was ever ready to talk as he sat milking and I believe he enjoyed the diversion particularly as his Dad, Uncle Albert, was not a talkative man. As a lively four year old I was always badgering Uncle John to let me try one of the intriguing three-legged stools. In the end he capitulated and handed me one for practice. After only a few minutes I not unexpectedly overbalanced and subsided messily into the flow of cow excrement running in the exit channel out of the shed. I hastily picked myself up, with heavy loss of dignity, trying to hide the disaster on my dress with my hands, whilst John hooted with laughter and steered me into the farmhouse to share the joke with Mum and Auntie Mary. I recall we then all fell about laughing, after which John was reprimanded as he was supposedly looking after me!

I never again tried a three-legged stool and it was only a few years later that the Salts also abandoned them in the post war expansion and modernisation of their dairy farm. As part of these renovations the interior of the former big barn was gutted and re-purposed. Gone was the great hand operated mangel wurzel mincer that had fed the cows in winter, the sacks of feed and comfortable bales of hay where I had played with a succession of kittens. In their place was a second whitewashed cowshed along with a number of extra stalls for the increased herd, as well as a milking machine. Electric power and plumbing must have been installed in the farm at that time. The talk was all about milk testing for tuberculosis and it was darkly discussed that some cows had been replaced as they had not met the standard. I recall anguishing over whether they were the ones I had particularly loved and privately set about identifying which cows remained in the sheds.

An important aspect of the milking process (that still endured well after the milking machine was introduced) was the need for the early morning jaunt to the roadside to exchange full with empty milk churns. With Bill in the trap, John Salt and I would trundle over the fields to the roadside. When we arrived at our destination I was always impressed by the weight of the full churns, that when clamped by Uncle John’s great hobnail boots, could only just be manoeuvred backwards onto the milk stand.

During the war years there was perpetual need for horse power. So that apart from Bill the pony who pulled the trap (our main transport), there were quite a few other horses on the farm including Diamond and her taller partner Ginger. These huge draught horses pulled well together and were much in demand for the heavy work of growing and harvesting the oats, wheat and barley as well as mangel wurzels for cattle feed. Harvest times meant very hard work for the whole family, as well as anybody else available. Friends and relatives from neighbouring farms as well as wives and evacuees would come and help and then this would be reciprocated. Whilst a time of hard endeavour, it was also a time for pleasant conversation with cool drinks and picnics under the hedges when there was respite for the workers. Those days of harvest by hand were very long for the men and their helpers. They frequently endured well into the night by the cool brightness of a harvest moon, whilst the weather remained clement.

During wartime and even afterwards harvesting was very much “hands on” and Albert and John Salt frequently cut hay with the swing of a scythe. Whilst I recall seeing land girls in the district, I do not remember there were any working at Field Farm on a regular basis, although they may have been before we arrived. The casual workers I recall at Field Farm were Italian POWs (Prisoners of War) who were accommodated locally and who helped out during harvest time. These men did such work as standing the corn stooks for drying and they would throw up bundles of hay on pitchforks to Albert and John Salt when the farmers were building a hay stack in the stack yard. The POWs often peddled bicycles to their work along the country lanes whilst singing lustily in Italian. However, they were made to understand this was not appreciated by loud derisive shouts from the locals. People were so ground down by the continuing, wearying interminable war and the presence of these people was a daily reminder.

Horse power at Field Farm

Whilst after the war the Salts continued for some time to use horse power, no doubt because it was what they had always done and recovery from war was slow, my post war visits showed more mechanisation increasingly appearing in the district. Tractors were commonplace and harvesting by the moon was but a memory with the advent of the tractor driven combine harvester. This innovation was not only much faster but required far fewer workers. Undoubtedly, the first combines were still developing and were an expensive, new technology, especially as they were only brought out for use seasonally. Consequently, in Melton the local farmers rotated the use of a combine harvester in the way of a co-operative, sharing the machine when required, as well as reciprocating with the work on each other’s farms. I remember standing wistfully regarding one of these innovations churning through a field, realising even as a child that I was watching the fading of an era, as horses were increasingly less of a mainstay on the farm. As well, the former sense of community around bringing in the harvest was also differently defined.

Whilst the winds of change were blowing keenly there was still much reliance on working horses during the war recovery. Fuel was still expensive and the “old ways” were well established. From boyhood John Salt had loved horses. He had learned to ride at an early age and still kept the saddle and tack from his first pony (now wreathed in cobwebs) hanging where his stall had been in the stables. I had grown to love horses whilst at Field Farm and as a child I was fascinated by the tiny saddle, at the same time recognising wistfully my future life in London would preclude such activities for me. Whenever I returned to Field Farm subsequently, I would include the stables in my rounds of the loved familiar places. At the time of the 50th Anniversary of WW2 when John Salt and I wandered through the farmyard recalling earlier times, I saw the tack was still hanging there.

Just after the war the Salts acquired Captain, a horse of whom I was terrified. He was over fond of human company and as soon as he saw the trap appear on Home Field he would come lumbering over and as his speed increased so did my shrieks of dismay, until finally he thrust his head into the back of the trap with Auntie Mary trying to dissuade him. I never saw him working on the farm and his stay seemed short lived.

Although John Salt never regularly rode the horses about the farm during the war years, he would go to occasional meets usually borrowing a horse from Alwyn Salt, one of his cousins with whom he was great friends. Alwyn Salt (1921-2007) was the son of Richard Ernest Salt (1888-1058) and Elizabeth Ann Alcock Salt (1883- ), who lived on Turnpike Farm (Richard was a brother of Albert Davies Salt). Alwyn later married Patricia A. Keyworth. As well as farming at Turnpike Farm, he also became the landlord of The Plough Inn in Stathern.

After the war when we holidayed at Field Farm the hunts and gymkhanas were much more regular. My father would take us in pursuit of the hunt, frequently struggling to speedily turn the incongruous Armstrong Siddeley around in the unaccommodating lanes and over the hazards of hump back bridges. Later John Salt’s wife Janet Taylor Salt shared his interest in riding which was when the Irish Arabian “Silver” came into his life. Eventually as the years passed the requirement for horse power rapidly diminished. John did not replace his working horses when they died and finally, when only the milk trap was being used and Bill had passed away, Diamond’s much-loved bulk was put into service. I recall gazing over the hedgerows in royal estate from her broad back when John Salt took her for shoeing at The Forge in Kinoulton. At her eventual much mourned demise, Bonny took over the final days of the trap and provided ultimate company for Silver.

As well as horses and cows the Salt family had a succession of sheep dogs called Gyp on the farm. John Salt enjoyed having a dog as a companion and they were always very useful with the cows. During the war years there were also a few pigs that I imagine were turned into the Melton pies my mother helped Mary Salt manufacture. As their stye was in the orchard I would regularly supplement their diet of swill and food scraps with windfall apples.

In the latter part of my evacuation, I moved from just observing the farm activities to participating in some of the regular routines. I daily followed Uncle John to chicken feeding and egg collecting for which he provided my own basket. The chickens at that time were white leghorns and at night despite having shelters provided, they preferred to roost as a flock on the lower branches of the huge trees beside the farmyard. They appeared as so many white tropical blooms hanging swaying in the night breezes. Behind the trees close to the farm there was a brick cottage known as Mrs? cottage, although I never met the incumbent. I recall being still quite young when visiting and the house was already completely tumbled down, although I never knew what had caused its demise. But by then John Salt had put it to good use as another chicken house.

During the war Albert and John Salt worked very hard, usually tackling the big tasks together, however as Albert’s energy was waning John took over many of the regular daily routines of animal feeding and mucking out, although Albert was always on hand for the milking. The men rarely left the farm and if they did, they still had to be back there by milking time. Their only regular absence was weekly attendance at the Melton Cattle Market. It was always much anticipated as a great occasion. Albert and John would leave the farm “shining and polished” it seemed to me in their best clothes, long coats and flat caps, as briefly they were able to swap their isolated busy lives for some welcome exchange with other farmers in the district. Whilst no doubt discussion topics about the world news and current farming issues were paramount, in the absence of phones John Salt was also able to connect with friends and set up Saturday night social activities. Mary Salt and my mother and I would also frequently attend the market, the animals in their pens being a never-ending drawcard for me.

Mary Oxby Salt

Mary Oxby Salt (1891-1968) was kind, compassionate and infinitely resourceful. She was a superb cook, something that also extended into commercial enterprises she undertook with the farm produce, such as cheese making, baking Melton Mowbray pies and selling eggs. Mary probably also sold vegetables as she was also an inveterate gardener regularly found digging, planting seeds and weeding in the huge vegetable garden behind the farm house. This was an enterprise in which my mother willingly helped and which supported my own tentative efforts to distinguish weeds from vegetables.

Mary Salt was also creative, excelling at sewing, mending, knitting and rag rugmaking for which she diligently saved suitable fabrics. She was both sociable and hospitable and organising the local knitting parties during wartime was an extension of her earlier active work in community entertainment during her youth.

Mary was very fond of her Oxby family and whilst she rarely took time off from her well-ordered routines on the farm, a favourite place to visit was with her brother David Oxby who lived with his wife Eliza Flavell Oxby at Lodge Farm, Kinoulton. David would often reciprocate and come to Field Farm. He was the adopted son of Mary’s parents: John and Martha (Sarah) Archer Oxby who lived at Hollow Hill Farm, Kinoulton. When she visited Uncle David, Mary would always take us along with her in the trap and we were invariably welcomed with a cup of tea and cake whilst the adults caught up with local news, and of course the progress of the war. The Oxbys were lovely hospitable people. It always impressed me that the farm house kitchen had a very low ceiling, but as David Oxby was particularly short of stature, which especially endeared him to me, my child’s mind conceded this was not a problem, but it might have been for his wife Eliza Oxby who was taller, dark and slim.

Mary Salt: The Fairholm sisters

Another person Mary Salt visited regularly was her niece, Gladys Fairholm. As Gladys owned a sweet and tobacconist shop in Nottingham she found it difficult to come to the farm. We were always particularly eager to accompany Mary on these trips as it also meant catching up with two of my aunts, as well as their four children, evacuees who lived with Gladys throughout the war. A special treat as well was Auntie Gladys’ ice cream because there had been instances of deliberate ice cream contamination in London and of course my mother trusted Gladys’ recipe. It was also Gladys who had originally helped us to find refuge with the Salts at Field Farm.

Meeting Gladys and two of her sisters later revealed not only Mary’s compassion but also her capabilities. Mary’s close relationship with her niece Gladys Fairholm extended also to Gladys’ other siblings: Nellie, Kate and Nancy, which was unsurprising when were told Mary had taken on the considerable responsibility of bringing the girls up when her sister Annie Oxby Fairholm died.

I had always been curious about a colour tinted, framed photo of some little girls on the wall of my bedroom at Field Farm. When I was old enough to ask who they were, I was told they were the Fairholm sisters, Auntie Mary’s nieces, who had no doubt once shared “my” room. As a child I was quickly satisfied by this and soon made the connection between the girls and their now adult persona. But as is often the case it was only much later when further questions occurred to me about the girls’ earlier lives with Auntie Mary, I regretted there was nobody to ask.

Mary Oxby Salt (1891-1968) came from a family of 8 children (3 girls and 6 boys, one adopted). Her parents John Oxby and Martha (Sarah) Archer Oxby were farmers at Hollow Hill Farm in the Kinoulton district.

The family grew up and Mary’s older sister Annie Oxby (1884-1916) married Reuben Fairholm (1883-1918) in 1906. The couple had 4 daughters: Nellie (1907-1916), Gladys (1908-1949), Kate (1910-1999)and Annie (Nancy) (1916-1993). However, sadly their lives were to be a series of tragic events. In 1914 at the beginning of WW1 Reuben Fairholm, who was a coal merchant, was conscripted as a private soldier into military service. Tragically two years into the War in 1916, his wife Annie Oxby Fairholm died 3 days after the birth of their youngest child (Annie) Nancy Fairholm.

As Reuben was still overseas on military service, Annie’s sister Mary Oxby Salt assumed the responsibility of caring for her nieces at Field Farm (the girls’ abode is repeatedly recorded at Field Farm during their childhood years). Such an act must have been one of enormous courage particularly during wartime. Mary had herself only been married 4 years in 1912. She and her young husband Albert Davies Salt were just establishing themselves running a dairy herd at Field Farm. Mary was also expecting their first baby, son John Richard Salt (1916-2007) who was born that same year of 1916.

For 2 years the Fairholm girls lived at Field Farm, awaiting the return of their father Reuben Oxby from war service, but tragically in 1918, the last year of the war he was killed while fighting in France. His estate was bequeathed to Kate Oxby (sister to his deceased wife Annie). It is possible this was in time honoured fashion because Kate was still a spinster, but it is also noted the Fairholms called their third daughter Kate after her, so there may have been a special relationship between Annie and Kate Oxby. As it was, Kate Oxby remained single until 1919 when she married Frederick Sentance. Whilst it was never talked about it seems possible Kate may well have provided some help for Mary at Field Farm in the early days with the young family, although she never actually lived there. Kate Oxby Sentance herself died in 1924, at only 33 years of age, whilst the Fairholm girls were still growing up at Field Farm. Mary and Albert Salt remained responsible for the girls’ upbringing and they lived at the farm until they went their various ways to marriage or a career). when Gladys Fairholm, the second sister, who remained a spinster eventually died, she left her estate to her aunt Mary Salt.

I eventually met three of Aunt Mary’s nieces after they had grown up and the women were quickly added to my list of wartime “Aunties”. Nancy Sharp (nee Fairholm) particularly, came frequently to Field Farm to visit with her husband Harry Sharp, who would often help the men with their tasks on the farm. Nancy who was vivacious, funny and caring became a good friend to my mother. It was eventually Nancy and Harry who trekked to the farm with the news that the war had ended. Harry handed my mother a Peace Rose that had been specifically grown and named as a symbol for the ending of war hostilities.

Nancy and my mother corresponded for many years after the war and there was an exchange of photos when Nancy and Harry’s only daughter Maureen Sharp arrived. The couple would always visit us when we subsequently returned on holidays to the farm.

Gladys Fairholm, who owned the sweet and tobacconist shop in Nottingham and never married we also grew to love. As evacuees my family has much to thank her for. Speaking of her recently with my cousin Jose Money (one of the children whom Gladys had sheltered during war time) she recalled Gladys with great affection. Jose remembered:

Arriving at Gladys’ home as evacuees, standing waiting, holding my gas mask while Mum (Madge Money) held Della (sister) in her arms. Gladys was a very generous lady taking us all in. It made me think how lucky we were! One time she came and stayed with us in London in our “prefab” after the war but she then was very unwell and sadly we did not see her any more.

I only recall meeting Kate Theobald (nee Fairholm), the third daughter, once. On this occasion I had awoken from my daytime nap along with David Money (another cousin who lived with Gladys). Both of us became instantly aware that the farmhouse was particularly quiet and we were alone. For London children this was already a trauma. (David’s first memory is of his mother throwing him across the room for safety onto a couch during an air raid). So, terrified we had been abandoned in the farmhouse we stood shoulder to shoulder by the pump and screamed. The roaring continued until my mother came to check on us and we were told everyone was just outside the door as Kate had arrived and they were all helping her put up a tent in “the lane” beside the farmhouse.

Whilst Annie Oxby Fairholm, Mary Salt’s sister may appear to have died from childbirth complications (as her child Nancy was born 1/4/1916 and Annie died only 3 days later on 4/4/1916) and whilst this may also have had some deleterious effects, her death was attributed to an inherited genetic condition: Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia. Sadly, she passed this disorder on to at least three of her daughters: Nellie Fairholm Manders; Gladys Fairholm and Nancy Fairholm Sharp. It is possible to wonder if this same genetic condition was also responsible for Annie’s sister Kate Oxby Sentance’s early death?

Mary Salt: Memories

Mary Salt’s experiences nurturing her sister’s family, as well as her own son undoubtedly contributed to her patient “unflappable” manner and “way with children”. Dealing with me as an infant born into the turmoil of war cannot have been easy. But I recall when I settled my face into a stubborn four year old frown, she would smile and say “Don’t be “mardy” and I would immediately want to please her! When I was very small still, Auntie Mary would delve into her vast store of potential child occupation and think of numerous delightful pastimes for a little traumatised evacuee to do. At the same time, she knew she was giving my often-troubled mother respite from my care. Mary Salt and I would go together mushrooming in the paddocks, me with my own little basket gathering cowslips and locating birds’ nests in the hedgerows of a “secret field”. Once some nests were located, Mary would return with me regularly for weeks so I could see the cycle of eggs cracking and babies fledging. Thus, I began to learn the ways of nature, so that when John Salt told of a nest of rooks he had found in a felled tree, where the birds even had knives and forks to eat their dinners, I knew it was only his tomfoolery!

When it was too cold for outdoor play Mary would often get out the ragbag, explaining the intricacies of making rag rugs to my mother as she applied all the material scraps she had diligently hoarded into interesting patterns. After knitting parties she would show me the delights of making families of woollen dolls, pompoms and cats’ cradles with scraps of wool, the skills of which in time, I passed onto my own grandchildren. Then one day when I was 12 Mary brought out her sewing machine and helped me make a never forgotten “grown up” pink dress with black spots. My sister Dawn Winks recalls how Auntie Mary would also sit for hours helping her to make dolls’ clothes on Mary’s several trips to see us in London.

Mary had a good understanding of how it would be for me when at last the war was over and I would have to leave my first home at Field Farm and adjust to a new totally different environment in London. Above all, she knew I would miss the animals, so one day close to my departure found us hidden behind the Melton Road hedge waiting for my mother to return on the bus from Nottingham. This pantomime was to surprise my mother (who would anyway have been primed beforehand) with a sweet grey kitten Mary had found for me to take back to London. I was ecstatic to have my own animal and well recall the steam train ride home with “Bambi” from Nottingham to St Pancras, begging my mother to let me have him out of his cage on my knee.

Leaving Field Farm was undoubtedly a traumatic experience. My young age meant I had few memories of London prior to evacuation, so that I was really saying farewell to the only home I had ever known and the first attachments I had ever formed. So, with my North Country accent, I returned with my mother and Bambi to live in the four walls of a confining house in London, meet my father for the first time and go to school. These terrifying new experiences were only a little ameliorated by the placatory promise of returning sometime to Field Farm for holidays.

Field Farm: Post war visits

Whilst I do not remember when we actually did return to Hickling Pastures for a holiday after the war, it must have been more than three years later, as we went by car, so I was at least 8 years old. Meanwhile the months between were peppered with correspondence to and from Mary Salt. It was also during this time that she wrote about the sad experience of waking one morning to find her husband Albert Salt had quietly passed away in his sleep. It was 1951. Quite soon afterwards Mary came to spend some time with us in London, sleeping on an old war camp bed.

When we did go to Field Farm for summer holidays there were many changes from my wartime experiences. By now, my father accompanied us and we had the car for the journey, which was as well, as two sisters had joined our family. At the farm there were still eggs to collect and milk churns to trundle, which now had to be shared with my sisters. Albert Salt’s absence was felt, but John Salt married in 1955 and with his new wife Janet Salt (nee Taylor) the couple worked together to establish an upgraded dairying enterprise at the farm. At the same whilst the pump remained, the farmhouse had been modernised with the outdoor toilet and shed replaced by a modern bathroom and kitchen facilities. An agreeable division had been made of the living area to accommodate the now two families at the farm. Mary Salt lived on to enjoy having help from Janet Salt in the domestic area of farm life and eventually cherish her two grandchildren, Richard Anthony and Jennifer Salt.

In the wake of post war devastation in London, as well as a dearth of work, my father decided to make a new start and in 1958 he removed our family permanently to New Zealand. Accordingly, we went again to Field Farm to say our sad farewells. However, correspondence continued with Mary as before and I was able to return to the farm and introduce my new husband, when we were on honeymoon in 1963. It was a wonderful but poignant meeting at the farm as it proved to be the last time Mary Salt and I met, as soon afterwards she went into care in a local nursing home. However, I continued to correspond with John’s wife Janet and met John and Janet once more at Field Farm in 1998 at the time of the 50th Anniversary of World War 2.

I was met this time not at Melton but at Nottingham Station by Janet Salt in the Land Rover. We were again able to enjoy each other’s company and I spent a most pleasant few days rambling over the farm enjoying memories of the earlier years with John Salt. We noted the passing of the dairy herd in favour of beef cattle and the other many changes wrought by the years. John said a trifle wistfully that he had really never travelled further than the Nottingham district in all his life. But I suggested to him maybe that was not such a bad thing. It was with deep sadness we made our farewells, knowing I was leaving John and my first home for the last time.

Janet Salt and I continued to correspond when she was accustomed to keep me up to date with the changes at the farm. It was a deep shock to hear of the loss of her husband John Salt who died in hospital after several heart attacks. John Richard Salt died on 10th February 2007. He is buried not far from his parents Albert and Mary Salt in Kinoulton Churchyard. Janet Salt still lives with family at Field Farm and we have continued to correspond.

Field Farm, Hickling Pastures has a lifelong place of great affection in my heart. It is where my mother and I found refuge in the desperation of wartime, that blossomed into ongoing friendship between our family and the Salts. Whilst many sacrifices are made in a time of war, gratitude must be given for the way the people of the Midlands of England opened their homes and hearts to traumatised Londoners such as us, for an indeterminant period. Whilst not all these connections were successful, they cannot take from many that were, to the degree that we were rewarded by the benefits of mutual friendship that richly coloured our lives and lasted a lifetime.

The Salt family of Field Farm.

The history of Field Farm and the Salt family began when Richard Salt (1849- )who came from Stanton by Dale, Derbyshire married Mary Davies (1853- ) from Kinoulton in 1881. The couple settled at Field Farm, Hickling Pastures, where their 5 children were born. They were: John Arthur Salt (1883- ); Albert Davies Salt (1885-1951); Mary Salt (1890- ); Richard Ernest Salt (1888-1958) and (Thomas) William Salt (1897-1918). The 1901 Census recorded the whole family was working together on the farm, including Thomas Salt, a brother of Richard Salt.

Then in 1910 the only daughter Mary Salt left Field Farm when she married John Boswell, a dairy farmer from Kinoulton. The couple were farming Black’s Farm in Kinoulton in 1939.

During 1911 John Arthur Salt, the eldest son married Elizabeth Alcock at which time it is assumed the couple established themselves at Turnpike Farm, as they were still living there in 1939. Whilst purchasing properties undoubtedly required access to finance, it was said that “Richard Salt was a man of means and had ultimately financed all his sons into farms in the district.”

In 1912 John Arthur Salt’s brother Albert Davies Salt married Mary Oxby whose parents John and Martha Archer Oxby farmed at Hollow Hill Farm. After Albert and Mary’s marriage they apparently continued to live at Field Farm with Albert’ parents Richard and Mary Davies Salt and his two remaining unmarried brothers, Richard Ernest Salt and (Thomas) William Salt. It seems very likely that Albert’s help on the farm was crucial, after his brother John Arthur Salt had left the farm. This would have been even more apparent by 1914 as the country was by now mobilising for war and Albert’s youngest brother (Thomas) William Salt had enlisted with a Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment. Whilst training William still worked when he could at Field Farm. However, he left when his regiment sailed for Egypt in 1915.

The same year (1915) the third brother Richard Ernest Salt also left Field Farm when he married Elizabeth Ann Dawn from Cropwell Bishop. The couple settled in Hickling to bring up their family, probably at The Blossoms because this was where they were living in 1939. Once he was able their only son Alwyn Salt, helped his father on the dairy farm. Later Alwyn also became the landlord of The Plough inn, Stathern.

Meanwhile back at Field Farm, whilst war continued Albert Davies Salt must have worked alone on the farm just with his elderly father Richard Salt and their wives. At the same time Mary Oxby Salt’s sister Annie’s husband Reuben Fairholm (a coal merchant) had likewise enlisted in the war effort and went overseas.

A sad event that was to change all their lives occurred in 1916 when Mary’s sister Annie died not long after birthing her fourth daughter whilst her husband Reuben Fairholm was still in military service. After this tragic loss of her sister Mary and Albert Salt brought the four Fairholm girls (under 9 years and with a baby) to live at Field Farm. The same year, 1916 was also the year Mary and Albert’s son John Richard Salt was born. Two years on, the girls continued to be fostered at Field Farm when towards the end of the war in 1918 the girls’ father Reuben Fairholm was killed in France.

At this time (1918) whilst Albert Salt probably did the major work on Field Farm it was still owned by his father Richard Salt. But at some stage Richard and his wife Mary left the farm in favour of Albert and retired to a smaller property that Richard had earlier purchased in Kinoulton Village. It is not known just when this was but it is possible the couple were still at Field Farm to help out when Mary and Albert Salt were coping in the initial stages of fostering the Fairholm girls. It must have been a very stressful time farming and bringing up five children in wartime conditions. It was also a time of grief for the Salts as in 1918 they suffered the loss of Richard and Mary’s youngest son William Salt who also died in France at the end of the War.

After Richard Salt and Mary Davies Salt moved from Field Farm their son Albert Davies Salt and his wife Mary Oxby Salt continued to live there until the Fairholm sisters grew up and went their various ways. When Albert Davies Salt died in 1951, Field Farm passed to John Richard Salt who lived there with his mother Mary until they were joined by Janet Taylor whom John Salt married in 1955. John and Janet Salt had two children Jennifer A. Salt and Richard Anthony Salt. After the death of John Richard Salt in 2007 Janet his wife and members of their family still live at Field Farm.

Avril’s labels to the photos in the gallery:

- Annie Oxby Fairholm sister of Mary Salt who died young leaving Mary and Albert Salt to raise her and Reuben Fairholm’s 4 daughters.

- Ordinance Survey Map showing position of Field Farm in Hickling Pastures

- (Annie) Nancy Fairholm Sharp with husband Harry Sharp. Nancy was youngest of the Fairholm sisters raised from birth at Field Farm by Mary and Albert Salt. Taken during 1950s

- Field Farm 1944-45 “collecting the eggs” left Jose Money [who was] evacuated [to] 222 Berridge Road Nottingham [to live] with Gladys Fairholm, sister of Nancy, niece of Mary and Albert Salt (also brought up at Field Farm). Rare visit of Jose from Nottingham, Avril Winks on right.

- Nancy and Harry Sharp at home, think Nottingham? 1944-5

- At Nancy and Harry’s home Avril pushing pram, believe borrowed from Nancy? Taken 1944-45

- Avril and Gyp’s puppies 1944-5

- John Salt and Avril 1944-5, Living in a world of adults I sometimes took them to task.. I had been rushing around hiding to deter my mother taking a photo with a camera that had to be held just right and still! As usual John sorted me out, suddenly finding a fictitious frog that needed my investigation and allowed my mother to click the camera! Photos whilst rare were also valuable to be sent to the unknown fathers!

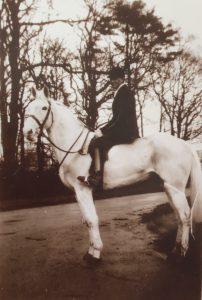

- (Devina) Dill Winks evacuee at Field Farm at Hickling with daughter Avril enjoying the hounds before the Quorn Hunt one morning. 1944-5 other people unknown!

- Quorn hunt the same as above. John Salt Centre, who was not riding this occasion talks with one of the huntsmen.

- visit in 1950? Dawn Winks, Avril Winks, Carol Winks showing my sisters the animals, here Betsy the calf that John Salt kept for us then took to market when we had left. Betsy had a stiff leg so could not run away from us.

- Visit in 1947? Only picture I have of Dear Albert Salt atop the hay rick being built in the stack yard with son John Salt and Gyp. Avril proudly wields a pitchfork, back “home” and in my element with sister Carol

- That lovely Diamond! The only horse on the farm I was allowed to sit on. John was a very careful man! Avril Winks 1948

- John Salt ready to join the hunt mounted on Silver probably around 1954

- In the trap always our transport up until 1955 when John Salt married and Janet had a Jeep/Land Rover. Diamond is in the shafts, Left Harry Sharp married to John’s cousin Nancy Oxby Sharp, John Salt, Avril Winks holding the reins with Carol standing and Dawn sitting. This was the trap in which Mary Salt had first brought us to Field Farm and the one in which John Salt and I had taken the full milk churns to swap for empties, hail rain or shine! taken around 1950+. Harry will have been making a social call but frequently he helped John with jobs on the farm when there was a need. Not sure of Harry’s trade, but he remained living at home during the war. I noted in the coloured photo of him he wears a medal??

- Last photo of Field Farm when I left for the last time in 1998 (I found the reel had run out!) Here outside the stables in the yard.

- One of the glorious apple trees [said to be] 200-300 years old. Their apples fed the pigs, and lent their perfume to the apple room long after thy were no longer stored there!

- 1963 My husband Jan stands under one of the mighty trees in the snow at Field Farm, one of the coldest winters for 100 years.

- A favourite photo of Avril Winks Thesing with Mary Oxby Salt my first Grandma; again that desperate winter of 1962-1963. Remains of the ancient “ridge and furrow” Medieval system of ploughing may be clearly seen with the furrows filled with snow. We were out on a walk retracing long ago bird nesting and flower picking expeditions of my childhood. My husband took the photo.

- TIME-BARRED: (please contact us if you are a member of the family and would like more information)

- These three photos show a now sixty year old tablecloth with lace made and embroidery accomplished by Mary Salt. It would have taken her many hours sitting beside the stove doing something as usual for someone else and undoubtedly a present of love. She must have begun making it sometime around 1960 when I became engaged in New Zealand and she gave it to me for my wedding present when I visited the farm on my honeymoon in January 1963. I have used it many times and despite having to clean it sometimes after family spills it remains as sturdy as it’s maker and will pass down as a treasured heirloom to my daughter.

“Undoubtedly a present of love”

“These three photos show a now sixty year old tablecloth with lace made and embroidery accomplished by Mary Salt. It would have taken her many hours sitting beside the stove doing something as usual for someone else and undoubtedly a present of love. She must have begun making it sometime around 1960 when I became engaged in New Zealand and she gave it to me for my wedding present when I visited the farm on my honeymoon in January 1963. I have used it many times and despite having to clean it sometimes after family spills it remains as sturdy as it’s maker and will pass down as a treasured heirloom to my daughter.”

Many of the census and documentary records for Hickling in the 1800s refer to tambourers (who created embroidery/lace work using a tambour or ring); the village had very strong links to the Nottingham lace industry with women doing ‘piece work’ from home. To see such an exceptional piece of work from a later time is a real treat.