(5/3/24: this is a first draft of this page – please let us know if you have any corrections or clarifications whilst we verify the content with experts more knowledgeable than ourselves!)

Anglo-Saxon/Anglo-Scandinavian hogback grave monument – Hickling

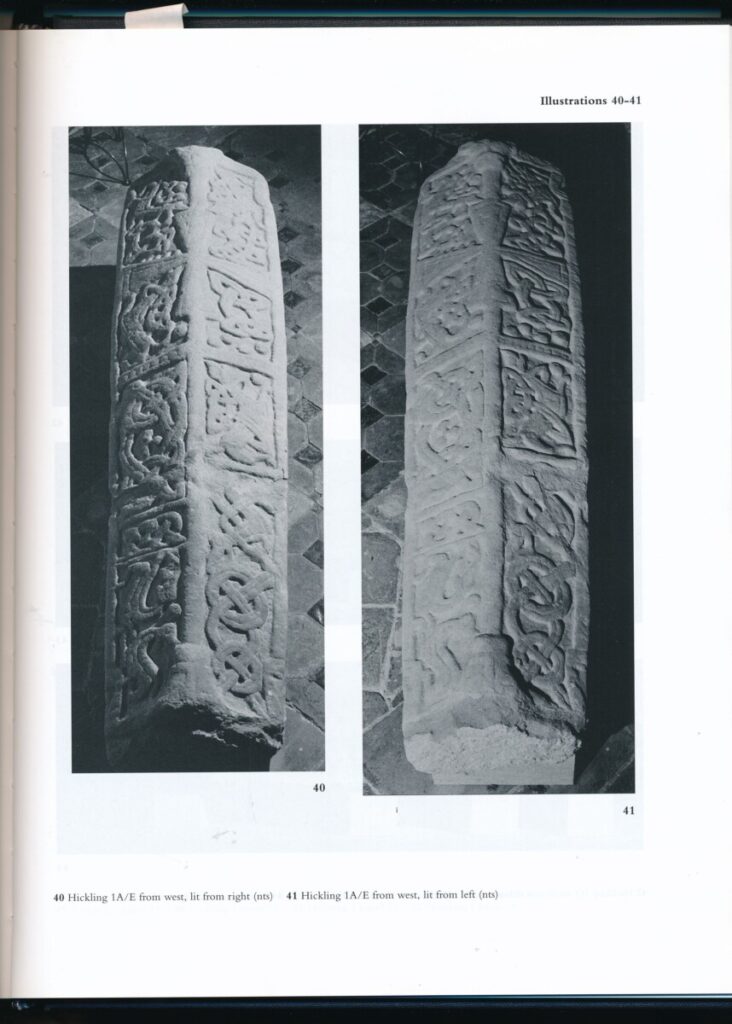

The Anglo-Scandinavian hogback monument preserved in St. Luke’s Church, Hickling is acknowledged to be of national importance. It is likely to date from the early 900s (tenth century) but could date as late as the mid-1000s (eleventh century). It is sculpted from Millstone Grit.

The motifs on the monument combine the pagan and the Christian and the monument has been reliably identified as a re-purposed half-column from a Roman building, possibly from a public building in Leicester (Rattae).

However, many questions remain:

- When was it sculpted?

- Who does the monument commemorate?

- Where was it originally located?

- Where did the re-purposed stone come from originally?

- Was it a grave cover or some kind of founder’s marker when the Church/Parish and graveyard were first established?

- When and where was it discovered in the modern era?

The term ‘hogback’ refers to the shape of these monuments which seem to have the shape of a hog’s back; they are only found over a relatively short time period and they are linked to Anglo-Scandinavian/Viking styles unique to the north of England during the early mediaeval period. This style isn’t found in Scandinavia and doesn’t seem to have been brought from there with the Viking settlers, instead they reflect new traditions emerging during settlement and integration with the indigenous Anglo-populations.

Leicestershire archaeologist Peter Liddle, explains that the shape was intended to echo/represent the pitched roof of a house. The Hickling stone is unusual in having elaborate designs along the long edges; more northerly examples often have a scalloped design that mimics roofing materials. The bears evident at the top and tail of the monument are seen from above as if you are looking down at the top of their heads and muzzles with their front paws extended round to the sides as if holding the ‘roof’ in place.

In addition to the hogback monument, Hickling Church has two mediaeval Cross Slab monuments; the most significant of these is the Tree of Life sculpture set into the outside west wall. The second example is inside the Church and on the opposite side of the chancel aisle to the more prominent hogback monument. It is much broader and more rectangular in shape but the design has deteriorated significantly. Sadly, little is known about this monument.

Christianity in Hickling.

It is likely that the location of the church and priest’s residence have been located in roughly the same area of the village throughout Hickling’s Christian history. However, their precise locations will have shifted gradually over time; archaeological records identify an Anglo-Saxon/early mediaeval graveyard slightly east of the current church building and this is a possible original location for the early mediaeval monuments now resting in St. Luke’s.

The first church building would probably have been a wooden structure with an earth floor and the congregation would have been served by visiting/nomadic priests. The first recorded rector was Adam, son of Robert de Hicklinge, who was instituted under the patronage of Sir Roger de Hareston on 21 July 1217 and he stayed in Hickling for seventeen years (ref: Chris Granger, A History of Hickling & All its Clergy).

The oldest surviving part of the Church building in its current location is the south section; the south aisle has a pitched roof possibly indicating an original stand-alone structure and an older sandstone buttress with stone walls is identifiably different to the mudstone walls of the rest of the building (which, unusually, appears to have been built alongside and attached to this older structure).

Viking Nottinghamshire: Hickling

(ref: Viking Nottinghamshire by Rebecca Gregory)

Terminology:

Anglo-Saxon? Viking? Anglo-Scandinavian?

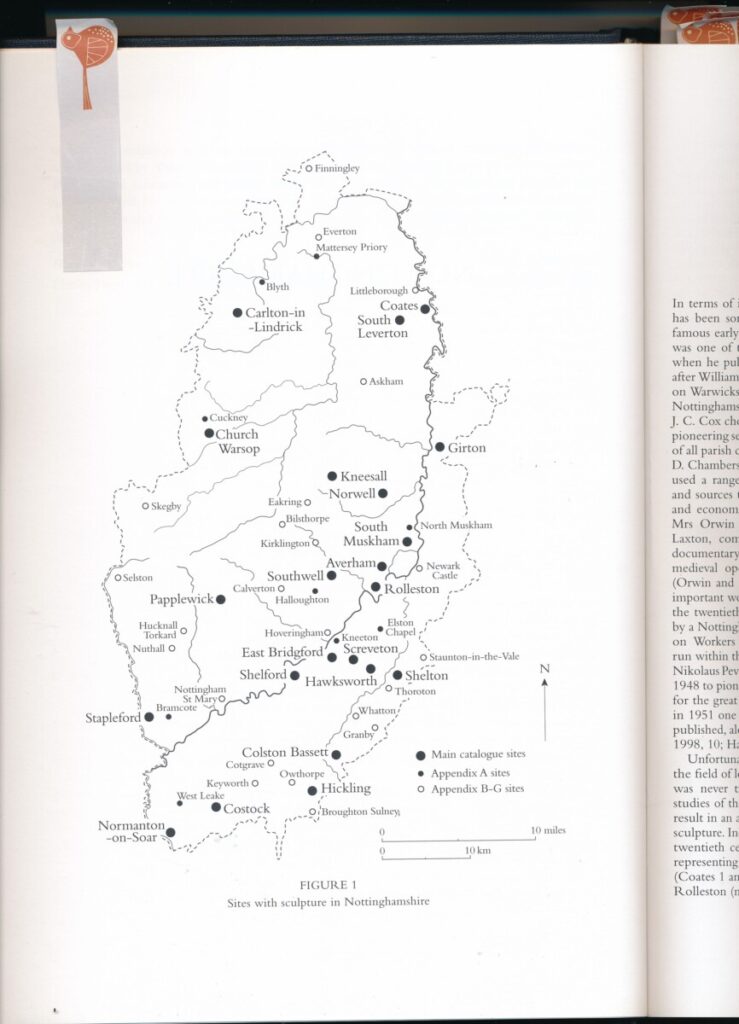

Archaeological finds and historical records indicate Anglo-Saxon and Viking/Anglo-Scandinavian influences in the history of the village. Hickling is situated in the middle of the Viking Danelaw and the name has an Anglo-Saxon derivation; however, place names in Nottinghamshire (and the villages around Hickling) range from Anglo-Saxon to Viking with some combining both.

- Anglo-Saxon: “A term used to describe the people who settled in south-eastern Britain from the fifth century onwards […] the general idea that the Anglo-Saxons began as a number of different groups of settlers is certainly correct. These groups eventually joined together to form kingdoms, although there were still local and regional groupings within those kingdoms. The Anglo-Saxons spoke a language called Old English.”

- Anglo-Scandinavian: “The culture which emerged in England following Viking settlement. The phrase can describe people, places, styles of clothing, jewellery or art and even language or dialect. Objects which are interpreted as being Anglo-Scandinavian often combine features from both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian styles and have developed additional traits unique to their context in Anglo-Scandinavian England. […] Old Norse; the language spoken by the Vikings who settled in England [and was] the spoken language of the ninth and tenth century Viking settlers.”

- Danelaw: The area controlled by Viking rulers in the late ninth century. Although it was largely retaken by English Kings in the early tenth century, it was still perceived as separate from the rest of England for many years.

Where Viking presence and influence can be seen in settled Anglo-communities, they are referred to as Anglo-Scandinavian.

Useful weblinks:

- https://emidsvikings.ac.uk/

- https://emidsvikings.ac.uk/?s=hickling

- https://emidsvikings.ac.uk/items/details-from-the-hickling-hogback/

- https://emidsvikings.ac.uk/items/details-from-the-hickling-hogback/

- https://emidsvikings.ac.uk/items/the-hickling-hogback/

East Midlands Vikings.ac.uk: The Hickling Hogback

A Viking Age grave cover at St. Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire

The Hickling hogback is a type of Anglo-Scandinavian grave cover in St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire. It is the most southerly grave cover of this type in England. It appears to have been carved from the remains of a Roman column, hence the notch in the end of it. The stone features Scandinavian Jelling-style decoration indicating an expression of Scandinavian identity and muzzled bears on each end which are thought to be indicators of a pagan identity. However, the stone also features a large cross showing that the commissioners of the carving had a strong interest in expressing the Christian identity of the deceased. As such, this stone is designed to show that the person buried under it was a Christian Scandinavian.

- Object Type: Grave-marker

- Date: circa 900 — 1030

- Style: Jellinge, Hybrid

- Ascribed Culture: Anglo-Scandinavian

- Original/Reproduction: Original

- Material: Stone

- Collection: Viking Objects

- Current Location: St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire

- Keywords: Anglo-Scandinavian, grave cover, hogback, Nottinghamshire, stone

- Further information: You can see the original at St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire.

- Acknowledgements: Photos by Roderick Dale

- References: Paul Everson and David Stocker, Nottinghamshire (Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture XII), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 115-25. A copy of this book is held by the Hickling (Notts) Local History Group and is available for reference, on request.

Carving out a new identity.

(abstract from Viking Nottinghamshire by Rebecca Gregory (2017) – pp48-51)

“Those people of Viking descent who made Nottinghamshire their new home had ties to two different cultures: to their ancestral homes in Scandinavia, and to their adopted home in England. Settlers with enough money and power found ways to articulate this new, Anglo-Scandinavian identity through objects, and some of the best examples of these objects are pieces of stone sculpture which survive from the period following the Viking settlement.

Stone sculpture was both expensive and time consuming to create. First, stone blocks had to be either quarried for that purpose, or reused from other buildings or monuments, in many cases travelling long distances before being sculpted. Sculptures were then designed and carved by master craftsmen with the skill to work stone, a long and laborious task. Stone sculpture was not, therefore, commissioned on a whim, and every aspect of it would have been carefully considered for the message it would send. If sculpture survives in a good condition, and can be decoded sufficiently clearly, it is full of information not only about the way its commissioners saw themselves but, just as importantly, about the way they wanted to be remembered.

[…]

“There are a handful of stone grave covers found in Nottinghamshire which have clear Scandinavian traits. They belong to a group of monuments known as ‘hogbacks’, which have a ridge running lengthways along the centre of the stone and are carved so that the highest point is in the middle – the metaphor is a straightforward one, with the stones having the same shape as a hog’s back. This type of sculpture is usually found in the north of England and southern Scotland, in areas of Viking settlement. Hogbacks are not found in Scandinavia, so they represent a new kind of sculpture created in England by Viking settlers who had converted to Christianity. The earliest examples are probably from the tenth century, and they seem to have fallen out of fashion by the twelfth. The examples in Nottinghamshire are unusual in being found so far south, and show a conscious choice to use sculpture associated with Anglo-Scandinavian culture, rather than imitating either Scandinavian or Anglo-Saxon monuments.

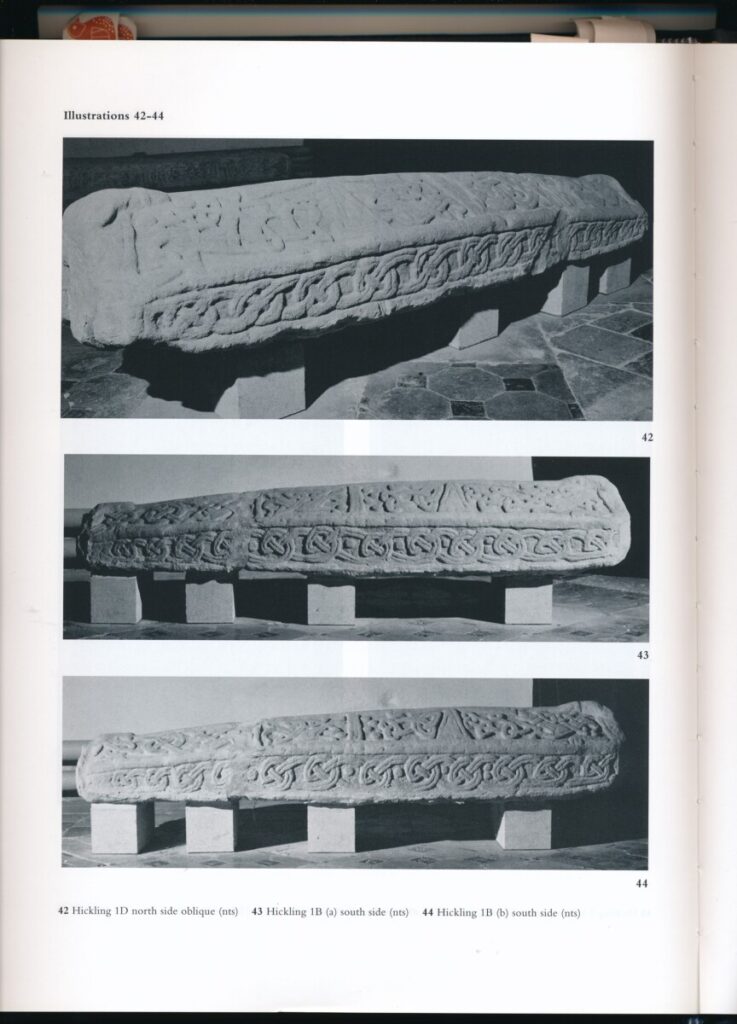

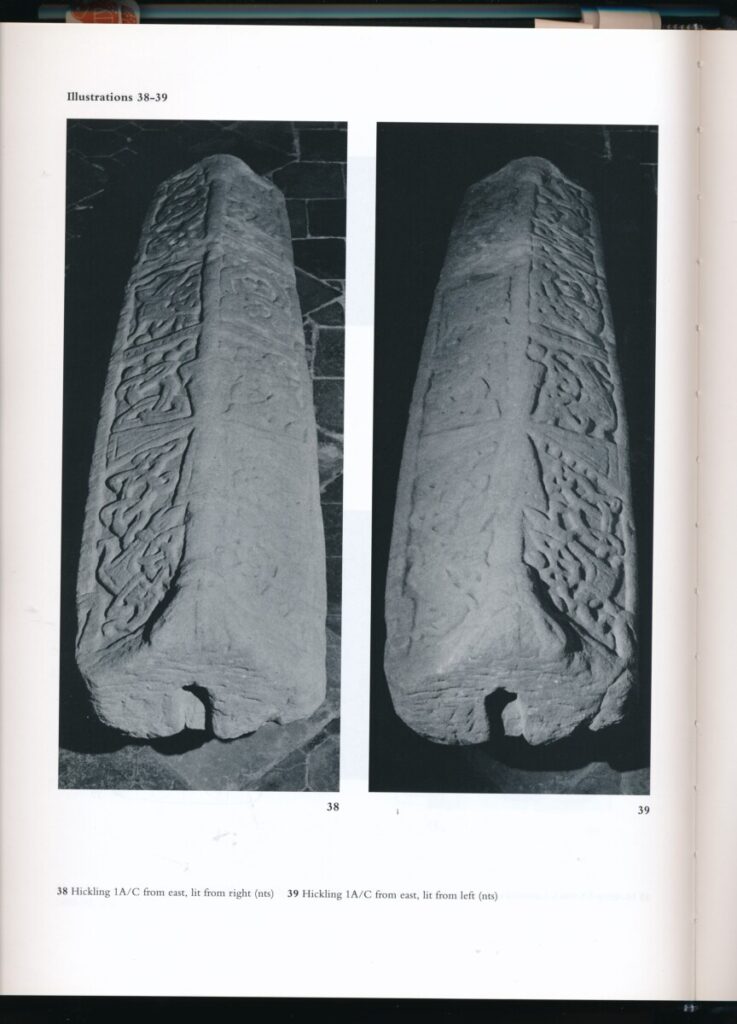

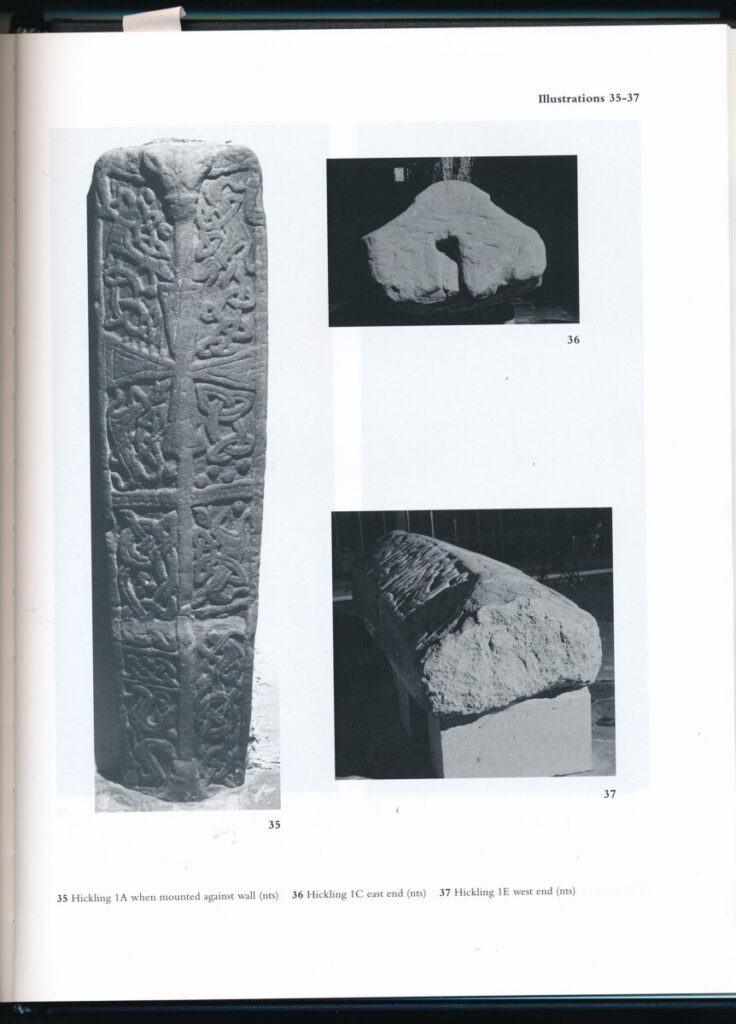

The hogback found at St. Luke’s Church in Hickling is almost completely intact, with a single break between two parts of the stone having been repaired. It seems to have been found underneath the Chancel of the church in the nineteenth century, and has been kept inside the church since its discovery, which means that it hasn’t suffered a great deal from exposure to the elements and the carvings on it are still clear to see. The hogback’s design contains features from a number of different sculptural traditions, and is consequently difficult to categorise. The stone out of which the hogback was carved probably comes from a Roman monument, perhaps in Leicester. Although the shape of this hogback is broader, longer and flatter than many others, this might be a consequence of the original shape of the stone rather than the choice of the sculptor. At the head and foot of the sculpture are two carved bears, a feature which is associated with classic hogback forms from the north of England. By contrast, however, on the top of the hogback is a cross, dividing the decoration; crosses are rarely found on hogbacks, and combining the bear motif with a cross can be seen as a way of mixing heathen Scandinavian traditions with Christian ones.

“There are two ways of interpreting this sculpture. Either it is part of an early tenth-century group of monuments which are part of a Hiberno-Norse (Irish Viking) tradition associated with the Kingdom of York, or perhaps it is an early eleventh-century piece associated with new Danish land ownership following Knutr’s conquest of England. The latest research on the Hickling hogback puts it in that first group of sculptures, showing the influence of York in Nottinghamshire in the tenth century. In this context, the mixture of traditional Scandinavian motifs and new Christian symbolism can be seen as part of a phase of growing integration between Viking settlers and the English population, even in the case of Vikings wealthy and influential enough to commission stone sculpture.”

Southwell and Nottingham Church History Project.

- https://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/hickling/hintro.php

- https://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/hickling/harchlgy.php#asgravecover

Anglo-Saxon Grave-Cover

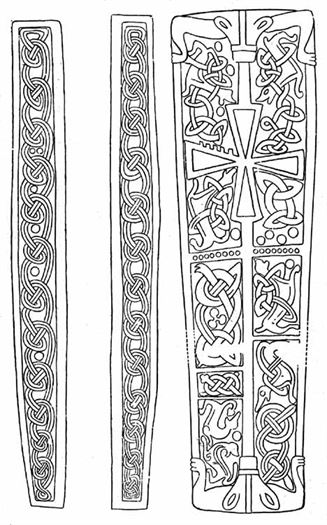

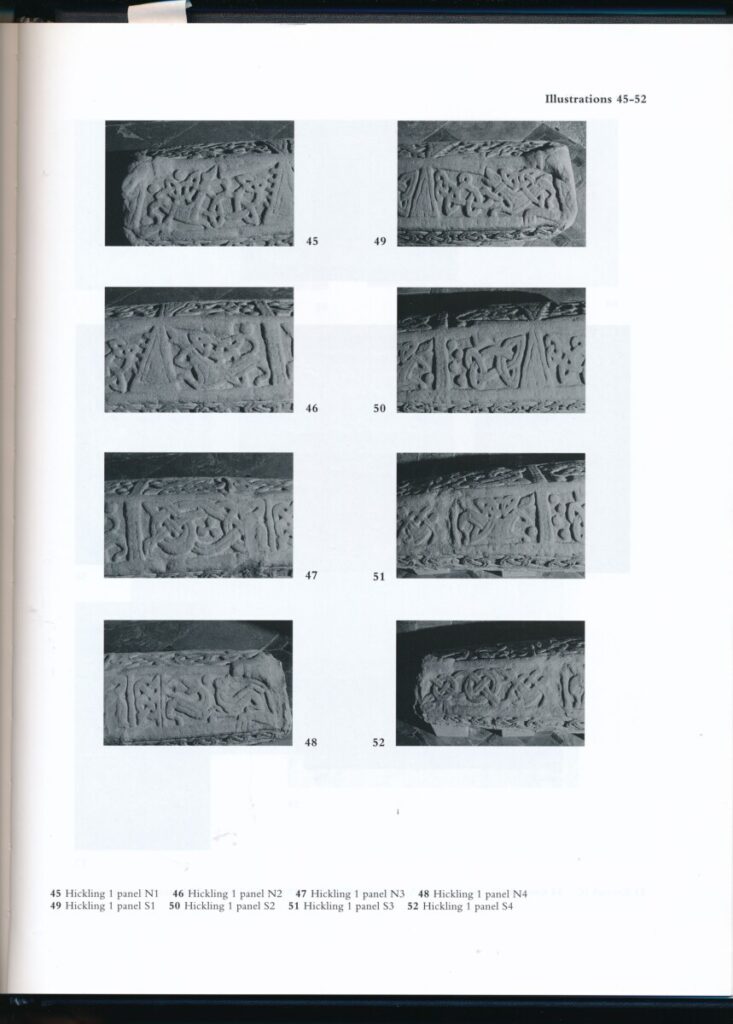

Located in the chancel north side, and moved here in 1999, is a large grave-cover of unique form nationally. It combines the northern Anglo-Norse hogback form with the large, coped grave-cover type more typical of the East Midlands. The upper surface is carved with unusual decoration in deep, low-relief, and is arranged in rectangular panels to either side of the central ridge. Towards the head the fillet of the ridge becomes the stem of a fine cross with straight, expanding arms. Below the cross-head is a bold, transverse bar that extends over the ridge and is decorated with a row of small, circular beads in low relief, and it divides the interlace and animal decoration on the lid into two distinct parts. There are schematic quadrupeds, interlaced knot decoration, bosses, snake, or bird, heads, and, at the corners, large, square fore-paws of a pair of bears. Dating is ascribed to the early 10th century or perhaps the early 11th century. A full description and analysis is published in Everson and Stocker (2016).

Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture; vol xii Nottinghamshire

(Everson & Stocker; OUP 2015)

A copy of this book is held by the Hickling (Notts) Local History Group and is available for reference, on request.

Context:

This title is a detailed academic study and contains extensive detail and comparisons linking styles, dates and characteristics. It is well summarised by both of the above quoted sources; for information, the following page references are useful to more detailed study:

- pp42-43: detailed exploration of the carvings and reference to the monument’s Roman’s origins; ‘The depiction is not so thoroughgoing, however, as to occupy the end surface and remove the evidence of the stone’s first use as a Roman column.’

- p53: includes detailed comparison of the Hickling monument to others in the wider area and to provide a context for dating the stone. Experts argue for origins ranging between the early C10th (early-900s) and the mid-C11th. However, Everson & Stocker prefer to date the stone in the earlier date range:

- Explaining that it is ‘formally a hogback’ without the usual end panels, “it has the bear terminals of that tradition and other decorative details susceptible of comparison not only with the small Derby hogback but also with sculpture in and around York. These characteristics suggest that it belongs to the early tenth century and the period of southward influence of the Viking kingdom of York. The important new perception that it is fashioned from a re-cycled Roman half column in Carboniferous Millstone Grit, which circumscribed the form this cover could sensibly take with minimum re-working, is perhaps a further factor pointing to an early-tenth century rather than a much later date …”

- pp80-84:

- ‘… unfortunately, positioning [the Hickling monument] securely in time and context is problematic. Although this ambitious grave cover is anomalous within the category in a variety of aspects, it is clearly of the hogback type characteristic of the settlement of Viking immigrants across northern England from the end of the ninth century onwards, even though Hickling is well south of their centre of distribution.’

- The Hickling ‘beast in combat’ motifs suggest the artistic culture of Viking York but also a small group of other East Midlands monuments. “All six monuments could easily represent burials of the incoming Anglo-Scandinavian elite, settling in newly appropriated lands, following the turning of the Great Army ‘to the plough’ after the 870s. It sometimes seems that the proposed dating of these monuments has been dependent on the view taken of the Viking settlement in the East Midlands. Understanding this process as a violent seizure of lands by the hostile mercenaries retiring from the Great Army might result in scholars dating novel and assertive monuments of this type to the immediate aftermath, perhaps to the final decades of the ninth century. A more collaborative view of the settlement process, by contrast, with retiring members of the international aristocracy marrying into indigenous families as opportunities arose, or purchasing lands with cash as they fell vacant, might result in the commissioning of such monuments somewhat later, perhaps in the first few decades of the tenth century once a truly Anglo-Scandinavian culture had been established and was valued. Our catalogue account inclines to a date, between around 900 and about 930 for this monument.”

- Links to a similar monument in Shelford are explored: “As the two monuments are technically amongst the finest pieces of Viking-age sculpture in England, we might be seeing here the flicker of a ‘Five Borough Renaissance’: a period of artistic achievement associated with the rapprochement (as characterized by David Roffe) between the Danish settlers and the indigenous population, overseen and guided politically, it would seem, by the Wessex kings and arising out of their victory at Tettenhall in 910.”

- “The important new observations in the catalogue that the Hickling cover is fashioned from a Roman monumental half-column and is of Millstone Grit in stone type might, interestingly, be the strongest evidence of its connexion with York, as a prolific source of spolia of this stone type and especially from public buildings. If that were the source, an analogy for Hickling might be the cross-shaft at Crowle in Lincolnshire, which is similarly an artefact of this era of re-cycled Millstone Grit from York. But the ruined public buildings of Leicester are potentially a nearer source.”

- However, the authors also put forward an argument for an equally feasible later date: “Unusually our account of Hickling offers an alternative date and context for the monument, in the early eleventh century. This line of reasoning derives from viewing the monument as a coped cover, and emphasizes the mixed, derivative and eclectic nature of its decorative detailing, and its ill-ordered handling. As an ambitious and distinctive commission, with a syncretic agenda combining Scandinavian and Christian symbolism, it would still be a grave-marker of a member of the Scandinavian elite, settling and probably converting to Christianity. But its context would be the era of Swein and Cnut, rather than a century earlier. As such, it would be rare evidence for a period little represented in the sculptural record of the region.”

- A third interpretation is also explored which aligns the monument with Viking Midlands traditions of the mid-900s.

- The authors explore ‘the period when the Trent valley had been settled by the Danes and pacified and secured by the Wessex crown’ when ‘an important section of the [Anglo-Saxon] local elite were incomers themselves, or the children and grandchildren of incomers, and part of a process of settlement that began with the ‘turning to the plough’ of the Danish armies in the area in the late ninth century.’ Noting the mixed iconography from the two cultures; Viking hogback form, pagan iconography and a large superimposed Christian cross.

- The Hickling and Shelton monuments ‘represent important evidence for the existence of churchyards at the date of their production and deployment. Experience elsewhere in the East Midlands suggests that they may well represent examples of the founding burials of local, presumptively parochial, churchyards and if they date from the early tenth century these Nottinghamshire stones are early examples.’

- ‘If the Shelton and Hickling sculptures do represent the first establishment of churches and graveyards for parochial churches at Shelton and Hickling alone, and not the graveyards of mother churches for entire hundreds [Wapentakes], then their dating makes them the earliest evidence we have for parish formation in Nottinghamshire.’

- “At Hickling there is the further evidence of a separate and putatively earlier graveyard, recorded as a group of burials some 225 metres south east of St Luke’s churchyard. As observed by the archaeologist Malcolm Dean, they were inhumations in ‘stone-covered’ graves – evidently not covers or markers in the sculptural sense, but loose stones – and, clearly lacking grave-goods, they were assessed as part of a post-pagan Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Nottinghamshire HER, monument no. M288; see Dean 1974, 45). Pioneering work by Professor Dawn Hadley in northern Lincolnshire has explored the phenomenon of multiple cemetery groups pre-dating and perhaps overlapping with a move to centralization of burial in a churchyard. Hickling may apparently offer evidence of a similar development, in which the remarkable grave-cover at St. Luke’s had a key role.” Further exploration of this research is included on p.84.

- Page references include: pp.1/2/9/36-39/42-43/53/80-84/89/128/346. The main section for Hickling can be found on pp.115-125.

The Hickling Chapter (Everson & Stocker):

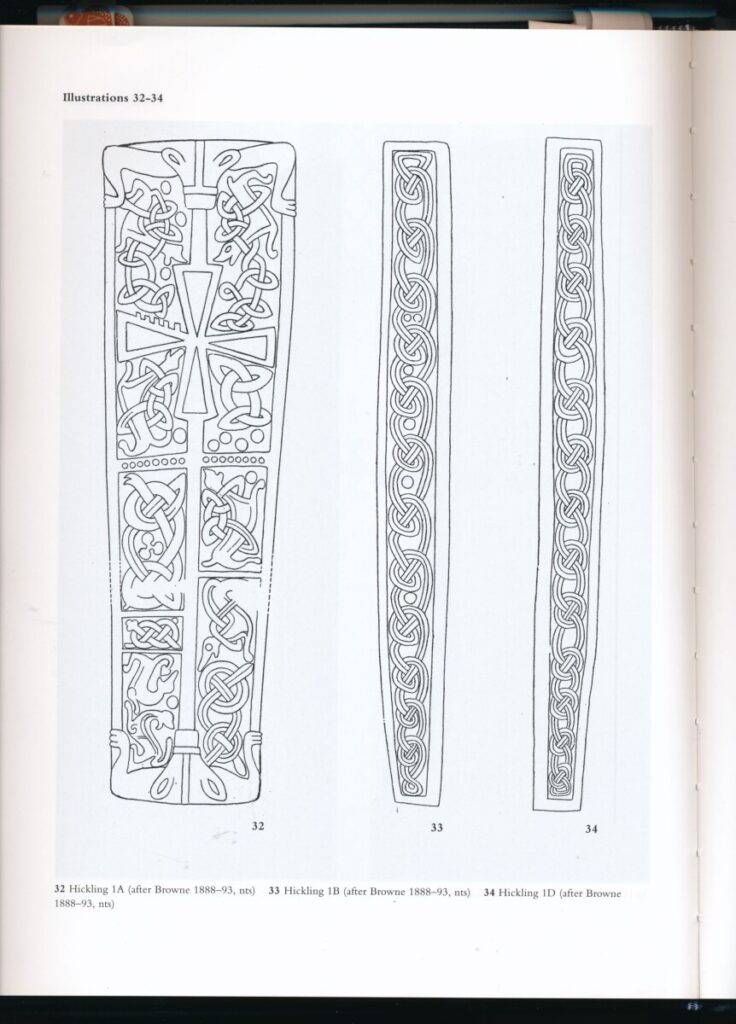

- (pp115-125 & figs 32-52/scans of these pages are available on request)

Evidence for Discovery.

“The monument was conserved and moved to its present location in 1999. Prior to that it had been mounted upright against the east wall of the south aisle and held in place with cement. The monument’s respectful upright position had already been achieved by the time that Godfrey wrote (1907) or Barrett visited in 1909 (Nottinghamshire Archives Office, DD/TS/14/32/3, p.23) and indeed already by September 1889, when a pencil field drawing was produced only partially recording the top’s decoration but with a side elevation and sections at the head and foot, all with dimensions noted, and was annotated ‘fixed upright against E wall of S aisle of Nave (ref. included). The cover had evidently lain on the floor of the chancel for a considerable period of time previously, which was where it was seen by Stretton in 1821 (ref. inc.). In that year Stretton also reported that it had been ‘dug up in the churchyard many years since in making a grave’, so we might imagine its recovery in the late eighteenth or in the early years of the nineteenth century. Irvine’s later nineteenth-century account of the discovery, which is full of circumstantial detail, appears to contradict this in respect both of date and location (Irvine 1890). ‘This stone, according to the testimony of an eye-witness now living in Hickling, was dug up from below the chancel of the present church on the occasion of the interment of the widow of a rector in the year 1826. From that time it lay on the floor of the church, and was found by the present Rector, Canon Skelton, at his coming, in a heap of coal. On the occasion of the restoration of the church in 1886, for its better preservation, it was erected in the east wall of the south aisle’. Irvine attempts, apparently deliberately, to reconcile this with Stretton’s report by suggesting that the early burial was probably originally outside, but became engulfed within the church’s footprint as its chancel was enlarged; but the dates of the cover’s reported discovery cannot be reconciled.

“The drawing of the stone which is frequently reproduced (refs inc.) was in the possession of the then Rector, FJ Ashmall, around 1900, when Godfrey borrowed it for his 1907 publication (ref. inc). It has not been clear until now whose work it represents. Unpublished inked drawings of the top and two long sides in the Romilly Allen Collection do not portray the peculiar jagged cross arm, and so seem to be independently produced, perhaps based on the pencil drawings in the same deposit noted above (ref.inc.). But, as Irvine notes (1890) the Rev. GF Browne had secured a rubbing, and he produced simplified line drawings of the top and both long sides as illustrations handed out in support of his first series of Disney Lectures at Cambridge in February and March 1889, when Hickling was the second monument illustrated and discussed (ref. inc). These are the drawings everyone since has reproduced.”

- The chapter includes detailed descriptions of the monument, its condition, materials and its decorations/motifs.

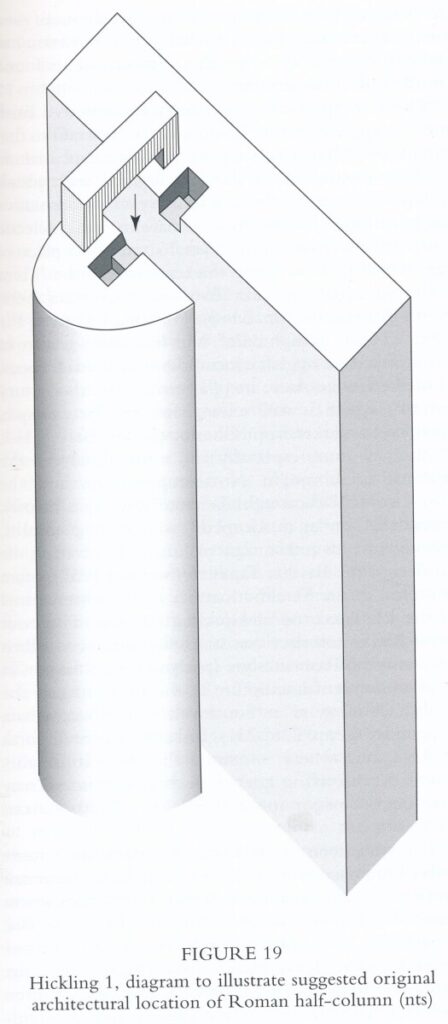

- “Critically, Hickling 1 actually retains within it direct evidence that this stone was not quarried for initial use as a funerary monument. The staple hole in the ‘head end’ is of a well-recognised form and must relate to a primary use of the stone as an architectural feature, and not as a grave cover.”

- The evidence leading to the theory that the stone repurposed in this way is fully explained; it appears to have come from a significant public building in Leicester and it ‘is possible that it once formed an attached half column, or respond, against an ashlar wall’ (diagram provided).

- The possibility that the monument might have been a ‘founder’s monument’ and not a grave cover is explored; Everson & Stocker refer to research identifying ‘a protracted attempt by the Church to gain control over burial during the tenth and eleventh centuries, of which the archaeological evidence at Hickling may be [an] example (ref. inc.). Perhaps the family of the Turkill and Godwin who held Hickling as two manors (ref inc) was the new lord, who (…) founded the church and graveyard at Hickling and marked that with a notable founder’s monument, using its decoration both to recall his Scandinavian roots and to celebrate his conversion to the Christian religion and cement his place in the local Anglo-Scandinavian community.’

- The authors also explore possible links to archaeological finds in Leicestershire from the period which may indicate they were sculpted ‘by the same hand’ and a possible ‘carver’s signature’.

- The symbolism of the bears is explored; particularly, that they may represent the conversion of the household to Christianity.

Galleries

Everson & Stocker – Hickling references and illustrations:

David Powell (copyright Nov 2020)

Southwell and Nottingham Church History Project:

Hickling – Introduction (nottingham.ac.uk): https://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/hickling/hintro.php