(Hickling gallery & ‘To Do’ list at the bottom of this page)

“He shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways” (Psalms 91)

This is the dedication at the beginning of Bernard Heathcote’s book, ‘Vale of Belvoir Angels’ and whilst the question of whether these carvings are angels or not is debated, Angels they are in the popular mind. It is possible that the carvings depict what is known as a ‘spiritus’ which represents the soul ascending to heaven; but either way, for most this translates as ‘Angel’.

In his extensive survey of the Belvoir Angels, Mr Bernard Heathcote records the earliest known Belvoir Angel in Melton Mowbray in 1681, the earliest in the Vale of Belvoir in 1690 in Redmile and the latest recorded Belvoir Angel in Old Dalby in 1759. He records 328 examples of which the largest number, by far, are in Hickling (33 (now 34)) and Nether Broughton (34). Gradually, a few more are emerging which were missed by the Heathcote survey.

The Belvoir Angels are a very distinctive example of localised folk art; they are a product of their historical and religious times. Inevitably, there are other examples which are similar because they have arisen out of a similar context – but they aren’t directly linked to each other; along the lines of, ‘a Labrador is a dog but not all dogs are Labradors’.

The Belvoir Angels are special because of these folk art origins, coming just before a time when design became hide-bound by national tastes & design books and because they originate over such a short and defined period.

Referring to them as ‘Belvoir Angels’ has emerged relatively recently (and, perhaps, was originally brought into use by the Heathcotes) but terms such as ‘Angel’ and ‘spirit’ and ‘soul’ are sufficiently fluid in our folk memories to be somewhat interchangeable; the term is a continuation of the original folk art impulse – a way of claiming our affection for them locally and connecting ourselves back to this point in our history.

(JF 2022.)

Characteristics of a ‘Belvoir Angel’

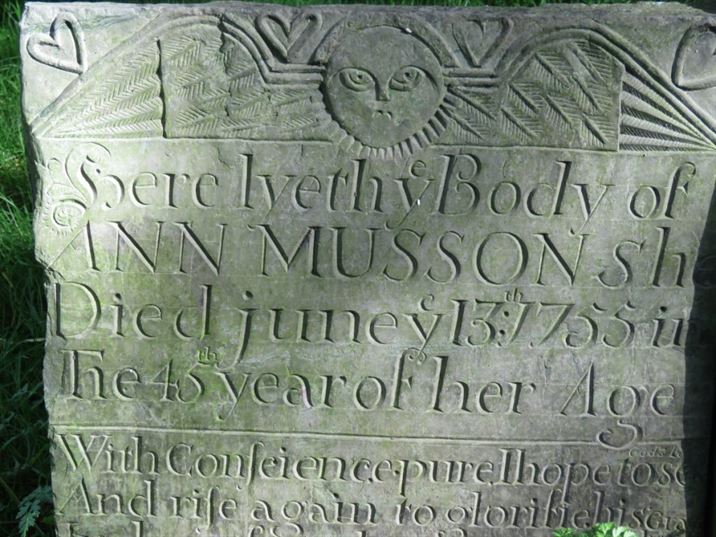

There is a very distinct character about the stonemason/s or craftsman/men behind the Belvoir Angels. It is possible that he/they were semi-literate (spelling mistakes and inconsistencies are common) but this may also be a simple reflection of a time when the written word wasn’t fixed and, as long as the result was sufficiently similar to the oral/aural version, then it was acceptable. Engraving typically moves from left to right with little sign of any planning or measuring – words that have been missed out are simply squashed in to roughly the right place; when space runs out the letters become smaller and fall out of line.

Each one is different and they all have a very vibrant, direct appeal to them.

Belvoir Angels are characterised by:

- One or two angels with down-turned, feathered wings

- Symmetrical triangular angel shape

- Stylised head & wings – front-facing

- A ruff around the angel’s neck

- They often have almond-shaped eyes

- They are not ‘prettified’ – some are quite sinister looking …

- Swithland Slate – rough hewn on the reverse (unless double-sided)

- Often carved in relief (like wood carving)

- Often include stylised hour glass, skull,

crossed bones symbols - The designs remain largely unchanged over a 60-year period

Many of the Belvoir Angel headstones are carved in relief (like wood carving); the stone is chipped away from the background of the design so that the angels are proud of the surface; the design stands out from, rather than being inscribed into the surface of the slate. This technique is much more time-consuming and takes a great deal of skill. One theory is that these were probably only affordable to the more affluent middle-class families emerging after the Civil War of the 1600s. However, the economics of pre-Enclosure society were very different to our modern era and it is possible that, in most cases, it wasn’t about money changing hands. As work begins on identifying the individuals belonging to headstones, it seems that most belonged to relatively modest graziers and yeoman and their families. Stonemasons would have been journeymen, travelling around their area as needed and they may have worked in exchange for board and lodging and/or goods as well as for money; this may, in part, explain how personal many of the headstones feel. The time given to carving headstones ‘in relief’ may also have a personal explanation – perhaps the stonemason knew some individuals better than others (family or friends) and wanted to demonstrate this by committing more time, effort and skill.

There are several local variations on the Belvoir Angels theme (and angels were a universally popular motif nationwide, anyway) but the distinctive Belvoir Angel is remarkable in that the carvings remained largely unchanged in style and technique for a full 60 year period; it is highly likely that they are all the work of one individual or family of craftsmen whose work was locally recognised as distinctive with a signature style not to be copied by other craftsmen. Or that it was simply a distinctive local style which was adopted and adapted through local familiarity and tastes.

There are a number of gravestones in Hickling churchyard where the lettering closely resembles the Belvoir Angel stones but without the angel engravings; they are all very low to the ground and could be either; earlier stones (in other words the style that the Belvoir Angels were based upon) or they are Belvoir Angel headstones which have lost their decorative upper parts. Otherwise, they may simply be variations – the angel motif wasn’t wanted or wasn’t affordable.

When surveying the Belvoir Angels it is recognised that many examples will have been completely lost over time or have simply deteriorated to the point that they are no longer recognisable. Others have lost some of their original depth and clarity, or they have lost bits of their slate or been moved – but it is remarkable that so many have survived for over 300 years.

It does seem safe to speculate that whoever he was he (or they) must have lived close to Hickling and Nether Broughton because of the density of examples in this small area.

Who carved the Belvoir Angels?

By the mid-1750s it became common for stonemasons to date and sign their work which may be a consequence of the increased use of design books – it became less easy to identify the work of a local craftsman simply from his style. To date, no one has been able to identify the craftsman/men behind the Belvoir Angels with any certainty.

Bernard Heathcote speculates that the Belvoir Angels stonemason/s could be earlier generations of the Wright family; John Wright is recorded as a mason and brick worker in Hickling between 1790 and 1830 and an old gravestone has been uncovered in the garden of his old home, Cobblestones. However, (at this time) there is no record linking earlier generations to these headstones. Interestingly, Mr Heathcote’s book records a number of Belvoir Angel headstones dedicated to members of the Wright family in Nether Broughton churchyard (1719-1733) – we hope to explore this in more detail, shortly.

Another route to explore includes wood carvings resembling the Belvoir Angels which were reported to have been found at Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire; unfortunately, no evidence of these has been found; nevertheless, an origin in wood carving does make some sense (for example, the relief carving on some headstones) and it may yet yield some useful possibilities.

Anecdotally (but certainly not verified), the story goes that the Belvoir Angels were carved by a father followed by his son – examples stop abruptly in the 1750s. It is said that there are remarkably similar engraved headstones in a small area in North America, possible Massachusetts (and nowhere else in the world) leading to an idea that the son emigrated and continued working, using the traditional unchanged Belvoir Angels style, for a short time in America.

David Lea refers to this (see, below) and he provides a link to the Farber Gravestone Collection – however, he indicates that these are more likely to derive from a similar inspiration rather than being directly linked. We are exploring this resource but haven’t confirmed any link yet. We would like to hear from you if you have any information that might help with this.

& some thoughts to ponder:

- Note: spelling and grammar weren’t really a fixed thing until much later (for example, Johnson’s dictionary/Georgian era onwards). Spellings which we now see as mistakes aren’t necessarily a sign of illiteracy – accepted forms were very different in the 1700s anyway and people often simply wrote phonetically (even names) without causing offence.

- That the stonemason originally worked with wood – there may be/have been carvings at Grimsthorpe Castle (for example) which may help with this. Some of the incredibly time-consuming relief work may support this idea (Carol Beadle).

- That the top and bottom sections were carved in advance (possibly years ahead) and then the middle sections completed when the headstone was ready for use; this could explain the irregular sizing and spacing (Stephen Cresswell).

- ‘Spiritus’ or ‘soul effigies’: a ‘spiritus’ represents the soul ascending to heaven, in America, more often referred to as ‘soul effigies’ (Bob Trubshaw). Ann Schmidt gives a useful route into this theory when she writes that, ‘all Belvoir Angels may be ‘soul effigies’ but not all ‘soul effigies’ are Belvoir Angels’. Belvoir Angels seem very earth-bound in their solidity and the way they look out at us; it is useful to try and untangle the religious thoughts and feelings of the period but it seems unlikely that the Belvoir Angels are an expression of a specific religious impulse or that they carried a direct message through their usage.

- The nuances of protestantism and the puritan movements are complicated in rural communities; different movements crossed over depending on the characters and personalities involved; including the tolerance or intolerance of individual clerics/rectors. The Civil War, still in living memory for those named on early Belvoir Angel headstones, will also have had its impacts but a village such as Hickling appears to have simply tried to just get on with daily life in such turbulent times, preferring to leave national politics and religious debates to others.

- it would be interesting to look into the protestant/puritan context of the period but, so far, theories appear to conflict with each other; on the one hand, some believe that carvings were removed by local puritans who disapproved of them whilst others see them as an expression of puritan identity. Either way, the images are very set in their ‘time’, depicting the ordinary appearance of individuals, whatever their religious persuasion.

- Lots to explore and discuss!

- There is also a thought that the number of angels reflects the number of people buried; this comes from the ‘spiritus’ theory where the Angel is a representation of the spirit leaving the body; thus 1 angel = 1 burial and 4 angels = 4 burials. This doesn’t account for names added later, and (in Hickling, at least) we haven’t found a direct correlation between the number of angels and the number of individuals commemorated. An idea for wider testing. (Bob Trubshaw)

- A curious example can be found in Eaton churchyard where an old roof slate (indicated by the hole) has been re-purposed.

- This stone was previously positioned up against the wall with the angel facing outwards and apparently without any names or dates. This led to the thought that it may be either a template that local stonemasons could copy from or a sample stone, used to show individuals wishing to commission a headstone. (P Hammond).

- This also led to the thought that stencils may have been used; if so, these would have defined the size and shaping of the lettering and then anything that didn’t fit would have been squashed in where possible (P Hammond).

- The repetition of verses across the Vale may support this and a roof slate would be a suitably portable material for this use. However, Thomas Blankley is an Eaton name which implies the slate is linked specifically to Eaton.

- This stone was previously positioned up against the wall with the angel facing outwards and apparently without any names or dates. This led to the thought that it may be either a template that local stonemasons could copy from or a sample stone, used to show individuals wishing to commission a headstone. (P Hammond).

Variations on the Belvoir Angels theme

The 60-year period covered by the Belvoir Angel craftsmen saw a huge change in techniques and styles; the introduction of ‘books of emblems’ aimed at stonemasons and furniture-makers and giving detailed examples of designs and calligraphy meant that styles became fashionable nationally rather than locally and engravings became lighter and more intricate. In contrast, the Belvoir Angel headstones emerged clearly from earlier styles of the 1600s which were shorter and squat with relatively crude lettering; over the 60 year Belvoir Angel period, the engravings stayed firmly in this earlier, cruder styling.

The highest quality period of headstone carving is seen in the mid-1700s – early examples in the late 1600s are very crude in comparison. Hickling churchyard contains many examples of Swithland Slate headstones outside the ‘Belvoir Angels’ tradition (see David Lea book for more on these). For example, the work of William Charles of Wymeswold in the mid- to late-1700s whose angels tend to be more chubby-faced (for example, in Hickling churchyard he engraved the headstone for Ann Orson in 1759).

Swithland Slate headstones.

Swithland Slate has been quarried from Slate Pits since Roman times – quarrying ended in 1887 after a slow decline and the slate pits are now disused and largely water-filled. Swithland Slate is a term used to describe early Cambrian-era slate found in and around the Charnwood Forest area in Leicestershire which forms a compact area of unusual geology in relation to its surroundings (see David Lea p5).

Swithland slate varies in colour through blues, greens, greys and purples with some areas being clearly identifiable by a predominance of one or other of these shades. It is a very hard slate and ‘does not have a well-developed cleavage’ (David Lea p7) making it hard to split into thin sheets – roof tiles tend to be thicker and heavier (than, for example, Welsh slate) but it is ideal for headstones.

(Article put together from local resources and with gratitude to the sources referenced, below)

Heathcote book scans Bernard Heathcote made an extensive survey of the Belvoir Angels with his late-wife, Pauline and these have been collated in to a comprehensive book recording their finds – unfortunately, this is now out of print and copies are almost impossible to get hold of; nevertheless, we have been able to include the Hickling pages here* (link, above). We are indebted to their research.

(*extracts reproduced in accordance with copyright and orphan works licensing regulations and are for not-for-profit research purposes only)

David Lea has written (and recently revised) a comprehensive analysis of Swithland Slate headstones and which he has very kindly made free to download – links, below.

As we focus on the Belvoir Angels, it is easy to forget that Swithland slate was used for many other styles of headstone, too. Many of these are around the quarry areas but there are no examples of Belvoir Angels close to the quarries themselves (Ann Schmidt).

David’s book covers the geological background (including blue, green and purple slate colours), an exploration of symbolism used on headstones from this period and the design books gradually coming into use. He also discusses the idea that the A46 may have been the route into the Vale for the slate itself; it is notable on Ann Schmidt’s County map of Belvoir Angel locations that they fan northwards from the quarries along the route of the old Fosse Way/A46.

Belvoir Angels, A Field Guide by Nigel & Barbara Wood (2011, Langar cum Barnstone Heritage Group)

Please click on the front page image (left) to explore Nigel & Barbara Wood’s excellent field guide to the Belvoir Angels.

Our thanks to the authors and the Langar cum Barnstone Heritage Group for their permission to publish it here.

Angels on their shoulders, with a shapely old yew for company by David Powell (2020)

Please click on the front cover image (right) to open his wonderful chapter on the Belvoir Angels. Our thanks to David for his permission to publish it here.

Please contact us if you are interested in the full book and we can put you in touch with the author.

Vanessa Stone; textile artist

A real highlight at our Belvoir Angels weekend (May 2024) was to be joined by Vanessa Stone who is a textiles artist with a special interest in the Belvoir Angels; you can find out more on her webpage: BELVOIR ANGELS — Vanessa Stone (vanessastoneartist.com)

A Belvoir Angels Map and Database:

We are very grateful to all those who have worked for many years on this project and whose research has led to an up-to-date database of the surviving Belvoir Angel headstones – thank you!

Ann Schmidt ~ Pauline and Bernard Heathcote ~ Alan Murray-Rust ~ Rod Gill ~ Nigel Morley ~ Alan McWhirr ~ Jane Fulford

The big advantage of a database project is that it can be updated and amended over time. Please contact us if you have new data or information to contribute and we will pass it on to the researchers involved.

Ann Schmidt has also produced a map of where the Belvoir Angel headstones can be found (by County); it is printed on A3 card with an information panel on the reverse:

These are available for sale for £1 at events or via the Belvoir Angels Facebook group or by contacting us.

‘To Do’ List – we hope to:

- Research the Wright family in Nether Broughton and then Hickling to see if we can confirm them as the stonemasons responsible for the Belvoir Angels.

- We understand that wood carvings at Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire are the same as the Belvoir Angel headstones: a recent visit and enquiries haven’t found anything at Grimsthorpe but it continues to seem worthwhile to look into wood carvings locally.

- Follow-up the possible American Belvoir Angels and try to establish a connection (if one exists …).

- Collect all the epitaphs across the 300+ Belvoir Angel headstones; analyse how often and when epitaphs were repeated and try to identify any patterns.

- We held our first Belvoir Angels weekend in May 2024 and a proposal to establish a Belvoir Angels Society has emerged – please contact us if you are interested.

If you can help with any of these areas, please contact us.

We are currently working on:

- individual pages for each of the Hickling headstones – these should follow shortly; a map of where to find each of the Hickling headstones is available in the porch of St. Luke’s, Hickling.

- following-up the Everard, Son & Pick/Ashmall correspondence which references photographs and information for the Hickling slate headstones in 1917.

The Belvoir Angels gallery is a simple photographic record of the gravestones loosely arranged from the west to the east in direction; most of them occur to the south of the churchyard around the south porch area. We are currently in the middle of recording the graveyard in detail – when this project is complete the Belvoir Angel gravestones will be included with transcripts and family histories as well as precise location markers.

Please note: this is a large gallery and may take a little while to load to your screen.