We are currently working on the parish registers and the census records for Hickling and information will follow as soon as we have it ready. If you have any queries, please use the general enquiry email address: info@hicklingnottslocalhistory.com .

Scroll down for: history, timeline, updates.

Census 1921: occupation records

The 1921 Census includes descriptions of occupations but also codes; explanations for these can be found on Find My Past – 1921 Census – occupation codes | findmypast.co.uk; please contact us if you are having difficulty identifying these records.

“Occupations were coded by the Census Office for statistical purposes. These occupation codes appear as annotations, in green ink, in the Personal Occupation column (col k in the standard household schedule such as C, E and W schedule type codes). An occupation code is usually followed by a forward slash and an extra digit. These occupation code suffixes after the slash indicate employment status. You may see occupation codes with the alpha prefix Y, which means that the individual is retired or no longer gainfully employed.”

Census 1921 update:

(January 2nd 2022)

1921 Census: the last publication for another 30 years!

& how many people will be able to search for their own records in the 1921 census?

The 1921 Census Returns will be made public on January 6th 2022 – almost 101 years after they were recorded and including 38 million lives. This Census was the first to record divorce and also the first to record detailed employment information; significantly it is the last time that most* of us will be alive to see the publication of a new census – the next one will be the 1951 census in 2051/2; the 1931 Census was destroyed by fire and there was no Census in 1941 because it was war-time; thank goodness for the 1939 Register.

(*Here’s a challenge: we’d like to hear from any mathematicians/epidemiologists who can work out what percentage of the population alive on January 6th 2022 will still be alive to see the next census published in 2051. Our guess at ‘most’ is based on – average life expectancies are in the low-80s; anyone born after January 6th won’t have been alive for this publication & is excluded – in other words, all under 30s in 2052; those currently aged 0-50 have the greatest chance of seeing the next census publication; in 2019 the over-65s represented 18.5% of the UK population (ONS); the 2011 census records the median UK population is age 39 and “21% of the overall population of England and Wales was aged under 18 years, 29% was aged 18 to 39 years, 27% was aged 40 to 59 years, and 22% was aged 60 years and over“ (gov.uk).

The 1920 Census Act decreed that 100 years must elapse before census records can be opened up, although they are available for authorised research purposes via the ONS (Office National Statistics) until that time elapses. The point of waiting 100 years is to minimise the misuse of sensitive private information; however, when the 1921 Census Returns are published there will be just over 15,000 people over the age of 100 – the majority of these will be able to search for their own records in the Census Returns (in 2011 there were approx. 11,800 centenarians).

- National Archives: Census records – The National Archives

- National Archives: 20sPeople: The 1921 Census (nationalarchives.gov.uk)

- Find My Past: The 1921 Census is Coming | findmypast.co.uk

NOTE: The cost of digitising the 1921 Census Returns is being recouped through fees for downloading records; whilst this has been controversial, it is hoped that eventually access will become ‘free-to-view’ (although via subscription to the usual family history websites) – when the 1939 Register was made public on November 2nd 2015 access was more expensive than this time and fees remained in place until February 2016.

NOTICE: Census 1921:

The Census records for 1921 will be released by the National Archives on January 6th 2022; they will be available via Find My Past. For more information, please follow these links:

- National Archives; 1921 Census online publication date announced.

- National Archives: Conserving the 1921 Census

- Find My Past: 1921 Census

- Find My Past: What does it take to bring the 1921 Census of England & Wales online?

“Taken between two world wars, during a period of economic turmoil and at a time when women had just won the right to vote, the 1921 Census will provide some fascinating insights about society and how it has evolved over the past 100 years. In preparation for the online publication, a team of hundreds of Findmypast conservators, technicians and transcribers have worked for almost three years to complete the invaluable task of getting the census ready. It is the largest project ever completed by The National Archives and Findmypast, consisting of more than 30,000 bound volumes of original documents stored on 1.6 linear kilometres of shelving.” (National Archives)

“The census is an amazing window into the past, giving us a snapshot of 38 million lives in England and Wales on one night in the summer of 1921. The census is stored in 28,000 volumes or pieces. Each piece contains between 300 to 600 schedules. For the entire digitisation project, they have been housed at a specially designed studio at the Office for National Statistics in Titchfield Hampshire, where they occupied 1.6km of storage shelving. There are approximately 8.5 million household schedules. If we laid every census schedule next to each other they would stretch across 4,675 kilometres, a similar distance between London and Boston.” (Find My Past)

“Another fun part of preserving 100-year-old documents is the interesting objects you find along the way. We discovered: 532 historic bugs, 12 used matches, 17 pencils, 4 erasers, Lots of tobacco flakes, One 1910 Belgian coin. During their time with the schedules, the bugs enjoyed nibbling away at the edges of the documents.” (Find My Past)

Census Records – why we need them & Census 2021; creating tomorrow’s history.

(March 2021) – Scroll down for National Archives; a Timeline; some extra facts

1939 National Register: see separate page

On a local social media post recently, a resident had a moan about the letter which had dropped onto their doormat that morning; “What’s all this census nonsense—they’re just being nosy!”.

Completing a census return is a legal requirement for all householders—and this resident is quite right, it is an invaluable source of information. Government has access to census information almost immediately and the data that is collected informs all kinds of decisions about the way our society functions. But, for the vast majority of us, we won’t have access to this data until 100 years after it is collected – deliberately beyond most of our lifetimes.

Collecting information nationally at the same point of time is a gargantuan logistical task; in the electronically connected days of 2021 this year’s census is probably the easiest ever. But when William the Conqueror gave orders for the Domesday information gathering exercise it literally involved men walking every mile of the kingdom (and if someone was reluctant to take part they didn’t just complain about nosiness, they had serious weaponry to hand …). The next attempt to gather such universal information came during Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth – The Protestation Returns gathered in 1642 aimed to record every male householder in the country. We are fortunate in Hickling that both our Domesday and Protestation records have survived.

There were clear political aims behind both of the above, but the start of the current census system has always had a more ‘social’ emphasis.

A National Archives Overview:

- National Archives Blog: Making the Census Happen

- National Archives: Pathe newsreel 1941 – counting animals but not people

- National Archives: Pathe newsreel promoting the 1951 census

- National Archives: How to look for Census Records

What is the census and why was it compiled?

The census is a head count of everyone in the country on a given day. A census has been taken in England and Wales, and separately for Scotland, every ten years since 1801, with the exception of 1941.

The object of the census was not to obtain detailed information about individuals, but to provide information about the population as a whole; listing everyone by name, wherever they happened to be on a single night, was the most efficient way to count everybody once, and nobody twice.

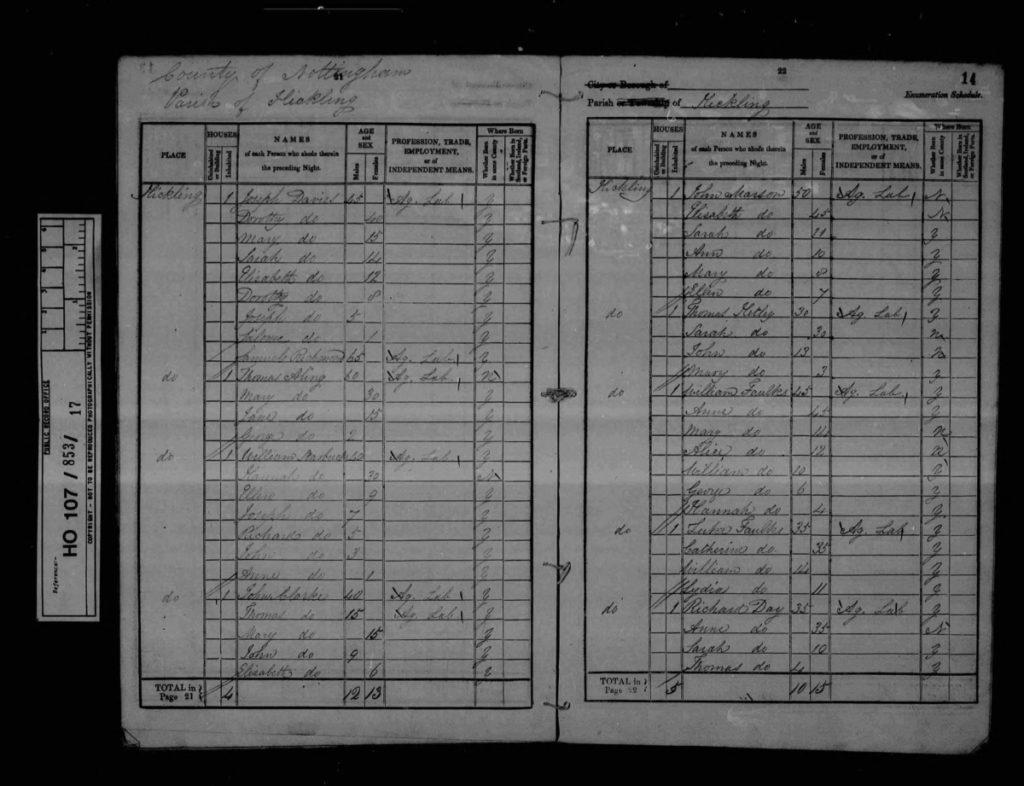

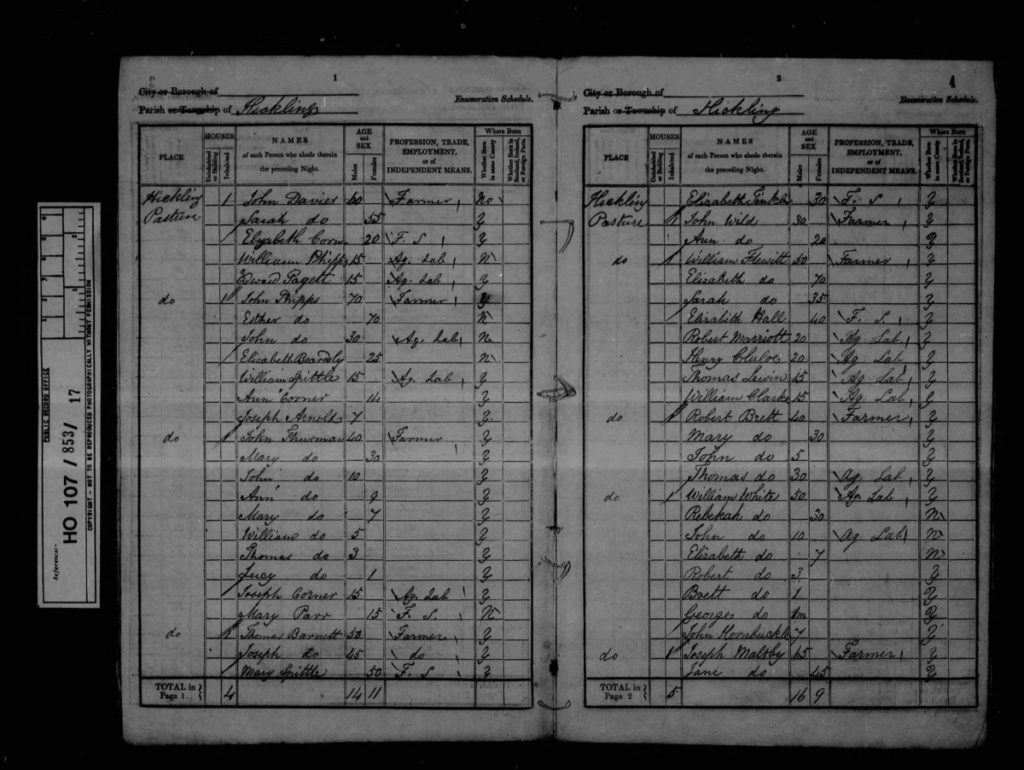

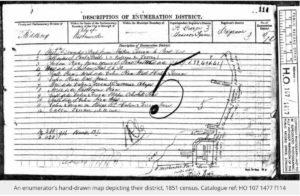

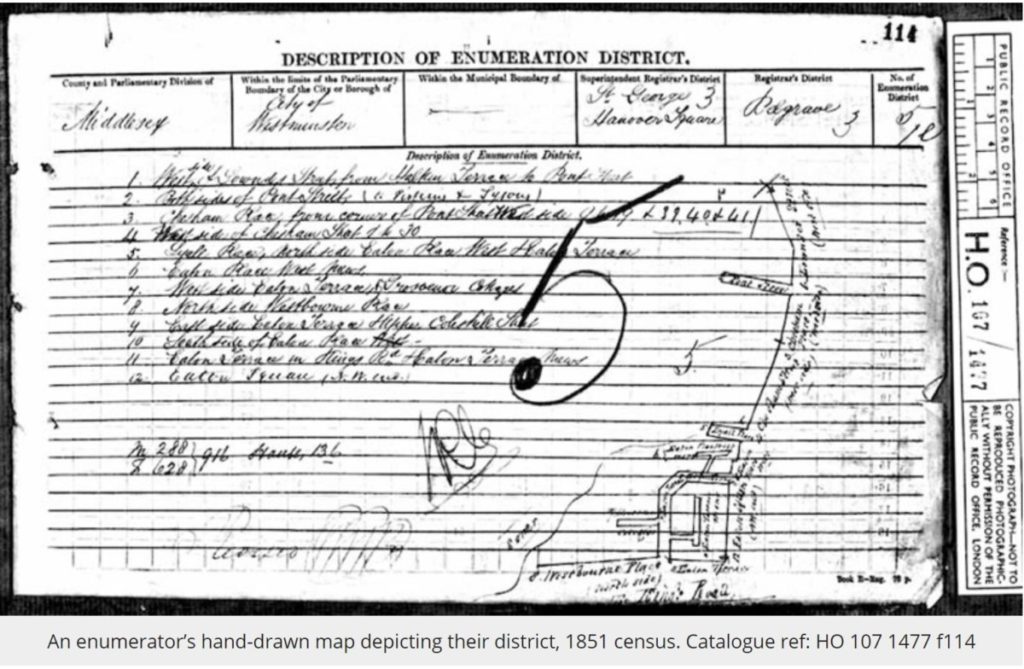

In every census year an enumerator delivered a form to each household in the country for them to complete. The heads of household were instructed to give details of everyone who slept in that dwelling on census night, which was always a Sunday. The forms completed by each household, known as schedules, were collected a few days later by the enumerator. From 1841 to 1901 the information from the schedules was then copied into enumeration books. Once the enumeration books had been completed, most household schedules were destroyed, although there are some rare survivals. It is the enumeration books that we consult today online or on microfilm.

The 1841 census was the first to list the names of every individual, which makes it the earliest useful census for family historians. However, less information was collected in 1841 than in later census years. The General Register Office was responsible for taking the census, so it used the administrative framework already in place for the registration of births, marriages and deaths. The Superintendent Registrar was responsible for collecting the returns from each Registrar of Births and Deaths in their registration district, and sending them to the Census Office in London. Each Registrar of Births and Deaths was responsible for a sub-district, which they divided into enumeration districts (EDs), and recruited enumerators for each ED.

In the censuses of 1801, 1811, 1821 and 1831 lists of names were not collected centrally, although some are held in local record offices. Other lists were sometimes compiled, for a variety of reasons, which are often referred to as census ‘substitutes’.

Unlike earlier censuses, the 1921 census (and later censuses) are subject to the Census Act 1920, as amended by the Census (Confidentiality) Act 1991 c.6 which makes it an offence to disclose personal information held in them until 100 years after the date they were conducted. Until then, they are held by the Office for National Statistics. Statistical information from these censuses is openly available.

(National Archives)

Timeline:

The dates of the censuses (published to date) were as follows:

- 1841 – 6 June

- 1851 – 30 March

- 1861 – 7 April

- 1871 – 2 April

- 1881 – 3 April

- 1891 – 5 April

- 1901 – 31 March

- 1911 – 2 April

- (2021 – Sunday 21st March)

Much changed as the census process evolved, particularly the amount and type of information that was collected; full information can be found at the National Archives, for example:

- Full details of the questions in all the censuses from 1801 to 1911

- How records are kept for naval ships and institutions such as workhouses, barracks and hospitals

- A guide to census terms and abbreviations

The censuses of 1801-1831 were produced by John Rickman, a statistician and parliamentary clerk. He drafted the first census bill, entitled “An act for taking an account of the population of Great Britain, and of the increase or diminution thereof”. Rickman asked enumerators to provide the numbers of males and females, work carried out in relation to agriculture or trade and the number of houses. He also asked the clergy to provide the numbers of baptisms, burials and marriages. To establish historical trends in the population, the 1801 census required the clergy to complete the unenviable task of providing data for the previous 100 years.

(Sunday Times 13th March 2021)

In 1821 enumerators were asked to provide the age breakdown of the population, information useful for organisations with insurance schemes. Almost half the population was under the age of 20. The figure now is reportedly just under 25 per cent. “Rickman suggested women might be lying about their ages, noting that “the number of females between the ages of 20 and 30 exceeds the corresponding number of males as stated in every county (except Monmouth)” “

In 1831 for the first time the occupation of women was specifically requested.

In 1841 the task for organising the form and the collection of data fell to the recently established General Registrar’s Office (GRO). “This is considered the first modern census, as each member of the household is counted individually, providing details of their identity, including name, age and sex. According to the historian Edward Higgs, the GRO hoped to expand the information gathered but was also keen to collect names to ensure enumerators were not making things up.” (ST)

In 1841 the basis of the questions for the future were established:

- first name and surname

- age (rounded down to the nearest five years for those aged 15 or over)

- sex

- occupation

- whether they were born in the county where they were enumerated (Y or N)

- whether they were born in Scotland (S), Ireland (I) or Foreign Parts (P)

In 1851 respondents were asked to record if they were blind or deaf and dumb; in 1871 and 1881 the list changed to read: ’1. Blind 2. Deaf and Dumb 3. Imbecile or Idiot 4. Lunatic’.

1851 included “an attempt to survey religion by asking clergy to record average congregations. According to Higgs, it was feared “irreligion” was spreading because of a lack of churches in urban areas for the working classes to go to, and “there was a need to understand how many seats there were for religious bums to sit on”. However, claims were made that non-conformist churches would pack numbers in their congregations to assert greater legitimacy than the Church of England. The religious question did not return to the census until 2001.” (ST)

1851 “A question on relationship to the “head of the household” is introduced, which has remained in some form to the present day. There is an implicit sense that the role is reserved for a man.

“Queen Victoria’s form is illuminating: under occupation she writes “Queen”, but she does not identify herself as head of the household. That is reserved for Prince Albert.” (ST)

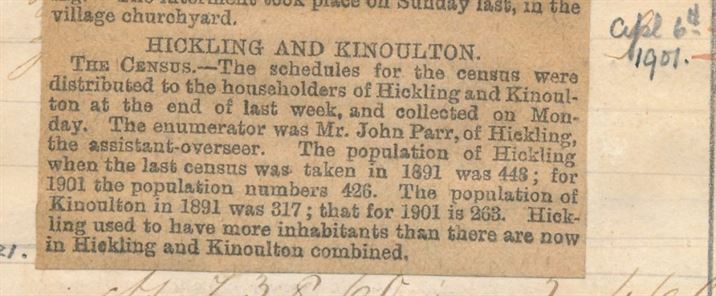

1901 An article in the Grantham Journal traces population changes in Hickling; our current population (2021) is probably as low as it’s ever been; the mid-1800s levels probably reflected the busy time for the canal and a very different rural economy (but much more work is needed on this).

1901 “One new question asking if people “work from home”. According to Higgs, this is to gather information about the poor working conditions of home workers and those in “sweated” trades. Sweating was defined as underpaid, unsanitary work, excessive in hours. Trades such as matchbox-making were mostly carried out by women and children, who toiled at home for long hours to produce the cases and trays that held matches.” (ST)

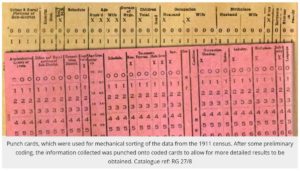

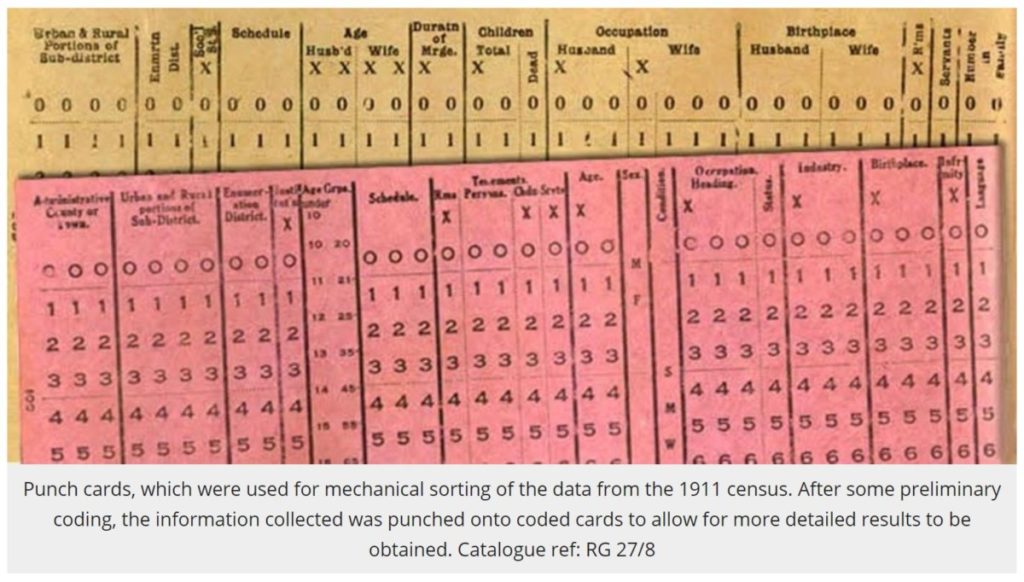

1911-1941 “A period marked by disruption and social upheaval, culminating in the cancellation of the 1941 census because of the Second World War. 1911 brings a great innovation in how data is collected, with the invention of the Hollerith punch-card machine. The Census Act 1920 sets out a minimum of five years between censuses. The 100-year disclosure rule also begins, meaning a full census cannot be released publicly for a century. The 1921 census will be available in January 2022.” (ST)

1911 “is known as the fertility census: there are concerns about falling birth rates, so married women are asked how many children they have had. The historian Simon Szreter suggests the question reflects a national debate on the perceived biological decline of Britain. The ascendant eugenics movement attempted to link high fertility with the working classes, which they claimed was an “evolutionary dead end”.” (ST)

1911 also acts as a platform for the suffragette movement, “Emily Davison, who died in 1913 by throwing herself under the King’s horse during the Epsom Derby, is found “hiding in the crypt of Westminster Hall” when the census form is collected, which is then recorded as her address. Some women protested by writing their medical status as “not enfranchised”, while others attached political posters to their forms.” (ST)

1921 “The census is postponed from April to June because of strike action. This is the first and only time the census is delayed and one of only two to take place in summer [the other being 1841]. The forms feature tick boxes for the first time …” (ST)

1931 “The UK is in the midst of a heavy economic downturn. The only new question — on internal migration — is a result of the delayed census in 1921, with suggestions that the summer date produced a skewed picture of where people lived. The question remains to this day..” (ST)

1931 The records for this census were lost in a fire in 1942.

The 1939 Register; this is in the public domain (see National Archives) with records blanked out for anyone still alive when it was made public. It is a simple listing of who was living at a given address when the Register was taken – it only covers England and Wales (not Scotland, Northern Ireland, Channel Islands or the Isle of Man).

“The 1939 Register was taken on 29 September 1939. The information was used to produce identity cards and, once rationing was introduced in January 1940, to issue ration books. Information in the Register was also used to administer conscription and the direction of labour, and to monitor and control the movement of the population caused by military mobilisation and mass evacuation.”

(National Archives)

1941 The only decade that no census was taken (although a Pathe newsreel was released to lighten the mood – the census of animals at London Zoo including a missing flee named Oscar and a cockatoo answering the question, ‘What is Hitler?’)

1951 “A new question on what amenities are available to a household is introduced: exclusive or shared use of piped water, cooking stoves, fixed baths, kitchen sinks and water closets. Higgs suggests this is due to postwar slum clearances and large-scale building of social housing.” (ST)

In 1981 the phrase ‘first person’ replaces ‘head of household’

In 1991 “The census of 1841 asked questions on birthplace, with the option of “Foreign parts” for those not born in the British Isles. The question remained in some form and served as a proxy for the ethnic make-up of Britain. The state was reluctant to ask a direct question on ethnicity because of the political implications for race relations, while ethnic minorities feared the enumeration would be used to create policies to marginalise them further. In 1981 the ethnicity question was tested but dropped from the census. In 1991, for the first time in history, respondents were asked to clearly state their ethnicity.

2001: “The form now has almost twice as many questions as in 1991. This is primarily down to an increase in questions on employment — from five to 15. The fraught question of religion, last seen in 1851, returns. It was again voluntary. Jedi is the fourth-largest religion in the country, behind Christianity, Islam and Hinduism (as well as “no religion”).” (ST)

2011: “In the first census to take place since the Civil Partnership Act 2004, same-sex civil relationships are included for the first time. Respondents are also asked to state their national identity, and were allowed to pick more than one out of British, English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish and other. A report from the Office for National Statistics recommending the question be included stated that the “2001 census drew strong opinion from people that wished to express a more detailed identity than just British”. (ST)

2021 “Voluntary questions on sexual orientation and gender identity will be asked for the first time. The census white paper — a policy document drafted by the government — suggests the answers will be useful in “monitoring and supporting anti-discrimination duties”. There will also be an explicit question for those who have served in the armed forces.“ (ST)

(The 1921 census returns will be made public in early 2022 (under the 100 year rule instituted in 1920); these will be the last returns to be published until 2052 because of the 30 year gap in the middle of the C20th (see, below).

2031 Will there be another census is 2031? The debate is on but it seems a shame if there isn’t – the ten-yearly national census is the opportunity for every individual to be recorded equally (and an invaluable research tool for all of us family and local historians!).

(ST: extracts from an article in the Sunday Times 13th March 2021)

Some extra facts:

- The census returns for 1931 were destroyed in a fire in 1942 and there was no census taken during WWII (the only time the census has been cancelled); this means there is a 30 year gap between 1921 and 1951 without census data – a period of massive change. Fortunately, in 1939 a National Register was taken which places everyone resident in the UK with their specific address; this is already publicly available although many records are blanked out where named individuals are still alive.

- The 2021 census will be taken on Sunday 21st March; the 1921 census results (under the 100-year rule) will be made publicly available in early 2022.

- Although the intention was to ensure no one was recorded twice there is no doubt that duplications have happened; the transcribers were human and fallible (in all their infinite variety) and the householder’s recall hasn’t always been 100% reliable. It is always sensible to try and confirm details by cross-referencing other records. (We may have an example of duplication in the Mark Starbuck story on our website but further checking is needed).

- Sometimes entire sections of the census have disappeared: “The 1841 census returns for the whole registration district of Wrexham, Denbighshire, were believed to be missing. However, the original enumeration books for the town of Wrexham were discovered in a bookshop, and are now deposited in the Denbighshire Archives.” (National Archives)

- Census information (over 100 years old) is in the public domain and available to everyone without charge (the National Archives at Kew are a good starting point for free records); however, free records are limited in detail and searching is very basic – specialist family history websites allow more accessible, wide-ranging and detailed research these days.

- 1911 was the first census where householders completed the census in their own handwriting—a fascinatingly personal record; 2021 will be almost entirely collated online (no handwriting!).

- The United Nations has 4 criteria for a modern census; individual enumeration; universal across the territory, simultaneous and it must happen at regular time intervals. The 1801-1831 censuses only ticked 2 of these – they were not simultaneous and individuals weren’t counted separately.

- There is ongoing debate about whether there will ever be another census after this one; apparently data is collected in real time in so many different ways these days that some believe a census won’t be necessary in 2031. Supporters of the census argue that the consistency & continuity of the previous system is valuable in itself and that it is a uniquely democratic way of recording every individual equally – watch this space …