A History of Hickling to 1860

and of all its Clergy.

Nemo me impune lacessit

by Christopher Granger

I am writing a history of Hickling from its very beginnings up to 1860 and of all its clergy. I do not intend to cover the remaining period, because Hazel Wadkin’s two books admirably cover the remaining period.

In the 1880s Hickling had a magazine called the Almanac. If anyone has any of them, *I should very much like to see them.

(Chris Granger)

Foreword

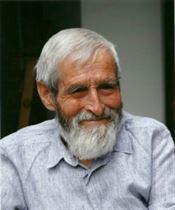

Christopher Granger was very much a Nottinghamshire man, his family being Nottingham’s last independent lace manufacturers. He also had close connections to several well-known Nottinghamshire families. On his father’s side, he was a great-grandson of Sir John Turney, leather manufacturer and Lord Mayor of Nottingham, and a great nephew of Professor Frank Granger of Nottingham University. On his mother’s side, he was descended from Richard Warwick, founder of the Warwick and Richardsons Brewery in Newark, and related to the Huskinsons of Langar Hall. Further back he was connected to John Robinson of north Nottinghamshire, pastor to the Pilgrim Fathers on the Mayflower.

Chris was born in Nottingham and spent much of his childhood there. After boarding school at Oundle and National Service in the Royal Artillery, he joined the family firm of accountants. But shortly after qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1961, he had the catastrophic misfortune of an accident in the Noel Street Baths, which left him with a severe spinal cord injury. Only the excellent care he received from Stoke Mandeville Hospital saved his life. It was here that he met his future wife Eileen, whom he married in 1964. Her skill and constant care kept him astonishingly fit both physically and emotionally through the years that followed. The arrival of the two children added an extra and hugely happy dimension to their lives, in turn much increased by the arrival of grandchildren.

Not entirely happy with his job with the national firm of accountants which had taken over the family partnership, Chris boldly set up on his own accountancy practice, and made a considerable success of this. This did not prevent him from pursuing an amazingly wide range of spare-time interests both historical and other. He and Eileen were often to be seen in Nottingham’s “theatreland”, attending plays, concerts and opera. These were complemented by visits to London and elsewhere. Indeed, determined not to be constrained by Chris’s condition, they frequently holidayed abroad. Nor was gardening out of the question. Chris’s great love and knowledge of plants led to creation of a garden with an extraordinary wide range of species. He also had a great love of beautiful books and in all these areas – gardening, books, theatre, opera, music – his enthusiasm was infectious and his knowledge astonishing.

But much of his leisure time (he never fully retired) was spent on his historical research. As a long-standing member of the Thoroton Society, the county historical and archaeological society, he attended many of its functions. He developed a particular interest in seventeenth century tokens, issued as alternative coinage by local businessmen because successive monarchs and governments failed to mint sufficient low value coins for everyday use. This led him to becoming perhaps the foremost expert on the tokens of the East Midlands and the people who produced them. He also explored his family’s history in numerous lines, on his mother’s as well as his father’s side.

But his major project in his later years was on Hickling Church and village, being on the final stages of this at the time of his death. He had been interested in parish churches ever since his time at school in Oundle, where he used to cycle out to visit and inspect the local ones. Even with all his other interests and activities he found time to write the history of Hickling church and its incumbents, on whom he discovered and organised an extraordinary amount of information. It is marvellous that this is now seeing the light of day. He combined this with the job of Church Warden here at Hickling for as many as 27 years.

When one considers the physical problems he faced – the difficulty in actually putting pen to paper, in travelling from place to place, in getting into buildings, just to mention only the most obvious ones – his achievement is astonishing.

Chris’s quiet and gentle manner was unchanged by his accident. A man of great intelligence, he held strong views but did not shout about them or force them on others. A life-long Liberal, he castigated the Conservative treatment of the disabled. In a marvellous example of his determination not to be dominated by his condition, he threw a party to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his accident and the start of his life in a wheelchair. That he survived 53 years after his accident is extraordinary and a tribute to the wonderful care and love he received from his nearest and dearest and the exceptional physique and determination of the man himself. He is sorely missed.

Christopher Francis Kendal Granger 1935-2015.

by John Hamilton

Editor’s Note (July 2020): Sadly, Chris didn’t complete his book and some sections are either incomplete or weren’t fully integrated as he intended – writing this book was a long, long project and there were always new reasons to tinker with it, alter it or to head down new paths. In reality, it may never have been completed but it is certain that Chris enjoyed the writing and the research and the end product may not have been his most important objective! Problems retrieving his research from an aged Mac computer after his death has also added confusion to Chris’s intended wording and, in some cases, we only have fragments. We hope that we have been able to retrieve the majority of his book and that we have been able to retain his voice and the spirit of his writing and research.

We are extremely grateful to his wife, Eileen, and the Granger family for allowing us to include Chris’s work in our Hickling archive.

Contents

* Chris’s manuscript was left unfinished in places and, sadly, it hasn’t always been possible to fill in the gaps as he intended.

** Chapters and sub-headings have been added which weren’t in the original text; this is to enable readers to navigate through the online text more easily.

*** source of images: ‘W’ = Wadkin Archive & ‘CG’ = Chris’s images from the Church History Project.

A History of Hickling.

(see also Appendix 7 for additional notes)

Chapter 1: Early to Sixteenth Century (also including:)

Chapter 2: Seventeenth Century Hickling (also including:)

Chapter 3: Eighteenth Century Hickling

Chapter 4: Nineteenth Century Hickling (also including:)

Chapter 5: War

Chapter 6: The Church and the Churchyard (also including:)

Chapter 7: The Value of the Church and its Living (taxation)

Chapter 8: The Rectory (see also chapter 7).

Chapter 9: Christianity (including:)

Chapter 10: The Clergy (including:)

Some Additional Notes (offered by a friend)

Appendices:

The following appendices represent material that we have recovered from Chris’s research but not incorporated in his main history. They consist of notes and fragments which, we feel, will prove both interesting and useful to his readers. In addition to the material here there are dozens of documents (unhappily mangled by the computer problems) through to the 1970s. Retrieving this research is a large project for another time but we may be able to help if you have a specific query.

Appendix 1: Hickling, A Chronological Table of Events in relation to National and International Events (to 1529).

Appendix 2: Table – Church Officers 1529 to 1977.

Appendix 3: Memoir of 27 Years as a Churchwarden of Hickling.

Appendix 4: Notes Relating to Artefacts and Dates.

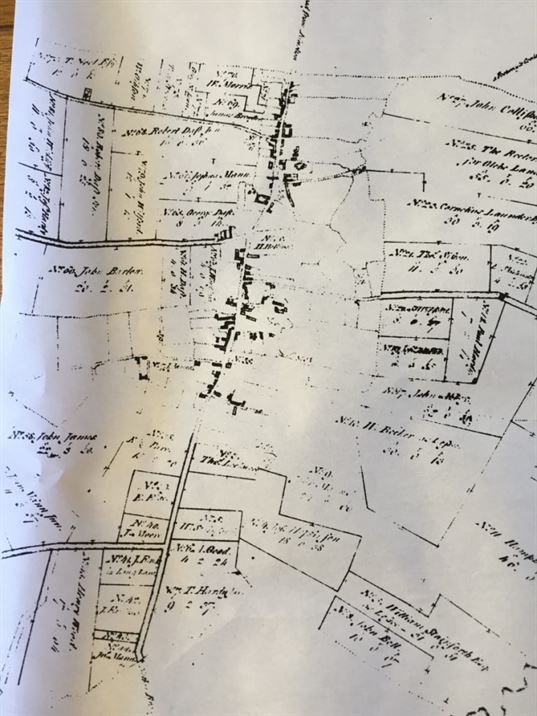

Appendix 5: Hickling Property (1856).

Appendix 6: Notes on Field Names, House Names and Road Names.

Appendix 7: Additional Paragraphs from Chris’s Notes (including:)

Appendix 8: Church Officers 1970 – 2013.

Appendix 9: Hickling Trades – seventeenth century.

Appendix 10: Fragment Transcripts of News Articles from the British Library Archives (1580s to 1930s).

Appendix 11: Churchwardens’ Expenses – 1700s.

Appendix 12: Articles of Agreement for the Enclosure Act 1714.

Appendix 13: Extracts from Parish Registers 1622 – 1764.

Appendix 14: Hickling Terrier 1663.

Appendix 15: Hickling Terrier 1687.

Appendix 16: Hickling Windmill (notes).

Appendix 17: Calendar of Patent Rolls 1553 (fragment).

Appendix 18: Hickling Villagers 1400s and 1500s (list).

Appendix 19: St. Luke’s Church, Hickling – Listing Descriptions

A History of Hickling to 1860

and of all its Clergy.

Nemo me impune lacessit

by Christopher Granger

Chapter One: Early to Sixteenth Century Hickling:

The Romans, coming from a civilised society, used coinage to facilitate trade. They brought their own silver denarii and copper aes and soon started minting in several places up and down the country. The Ancient Britons had issued their own small silver coinage. The pieces were very crude and look as though they were designed by cavemen and the images were frequently misplaced on the flan.

After the departure of the Romans, the coinage gradually dropped out of use and a system of barter prevailed.

It is not known whether people continued to live in Hickling from then on but it seems likely. When, later, the Vikings or Saxons came on the scene, they would choose a place where there already was habitation.

Hickling was settled in Anglo Saxon times by a tribal war lord by the name Heckla and his armed men carrying their axes, spears and swords, followed by their women, children and hangers on. Ing is a Saxon suffix used as a patronymic. This would have been sometime between 700 and 1000 AD. Hordes had been moving across Asia to find greener and safer pastures. These displaced the indigenous peoples who in turn flooded West and over into Europe. Jutes originating in Jutland and Saxons from Eastern Germany found refuge in this country, competing for land with the Vikings and pushing the Picts and Scots further north.

Before they left their erstwhile homes, the Anglo Saxons would have been organized into civilizations, whereas the Vikings were in general mere marauders. They quickly divided the country into kingdoms such as Wessex, Northumbria and Mercia. These kingdoms each had their armies and fought over their territories.

The Anglo Saxons, while controlling the country, suffered continuing harassment and occasional invasion from Danish marauders. In order to placate them, they were forced to pay large amounts of ransom money or Danegeld. They minted large amounts of silver pennies, most of which found their way to Scandinavia. This had to be out of someone’s pocket and the unhappy people chosen were the landowners.

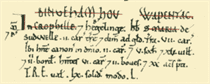

For this knowledge we must be thankful for the early records of landowners in the Domesday book which was a survey of land ownership for taxation purposes. The land was measured in carucates, the equivalent of eight bovates or oxgangs, which were the measure of the amount of land that a man and his ox could plough in one year. Meadows were measured in acres.

The earliest record of the existence of Hickling is in 971AD, when Aernkitel granted some land in Hickling to Ramsey Abbey.

Thomas Thoroton in his History and Antiquities of Nottinghamshire, which was written in the 1770s, wrote that immediately prior to the Norman Conquest, the whole parish consisted of two manors, which belonged to Torchill and Godwin. They were deprived of their lands by William the Conqueror who gave them in the form of two Manors to Ilbert de Lacy, forebear of the Earls of Lincoln, and Walter de Eyncourt, whose grandson, another Walter, restored it to Elias, or Elisius de Fanecourt, who held three parts of the land in Hickling and Kinoulton, of which his father, Gerard de Fanecourt, held of the Earl of Lincoln one Knight’s Fee . The village was then part of the larger parish of Cropwell, which also included Kinoulton and Granby.

Gerald was a great benefactor of Thurgarton Priory and he gave his Manor in Hickling to the Priory.

Ilbert de Lacy leased two parts of the “Town of Hickling” by free farm to Robert de Hareston for nine marks a year. This long lease passed by inheritance successively to the de Grey and Leake families and with it the advowson or patronage of the benefice of Hickling. This can be seen in the section of this book relating to the Clergy. Both the de Harestons and the de Greys took advantage of the advowson by providing a cushy, well paid job for a younger son, who merely had to take the cloth.

The long chain of inheritance was finally broken in 1542, when Francis Leake sold the Manor of Hickling and the advowson to John Constable of Kinoulton for £276

He quickly sold it on to John Ingleby of Ripley in Yorkshire. whose family retained it until in 1604. A later John Ingleby who lived at “Hickling in the Vale” sold the Manor and most of its land and the advowson to William Fairbarne, a resident of the Village whose father, Brian, is described in his will as a yeoman, for £534.

The Inglebys were held in deep respect by some of their tenants. One of them, Rauffe Patchingham, described John Ingleby as “my Worshipfull Mr Inglebye Esq. He possibly felt a little insecure because he had come from Norhamptonshire, where he had two married daughters, and become a tenant farmer in Hickling and had been a church warden in 1553. He would therefore been concerned at his advanced age for his elderly wife and spinster daughters.

William Fairbarne’s son, Gervase, who acquired the remaining land, inherited the Manor from him. From them, according to Thoroton, it passed to the Stapletons. William Stapleton was church warden in 1553. However, I have found no evidence of the presence of Stapletons in Hickling in the 17th century. Gervase himself settled in Barrow upon Soar.

Thoroton then loses track of the ownership of the Manor and lands. In 1585 a James Wilson and a George Warde claimed some land off a John Smith alias Walton and a John Smith who called William Vaux, Lord of Harrowden, as witness. It seems that the Smiths must have prevailed because the Smiths continued to live in Hickling for another one hundred and fifty years. The Smiths’ forebear had been a self made man from Nether Broughton.

In fact by 1629 the freehold of the manor had passed into the hands of Francis Maunsfield of West Leake whose descendents the Mansfields held it for some two hundred years. George Daft, a wealthy yeoman, in his will dated 6 June 1613, left the manor house with all its lands and tenements to his fourth and fifth sons, his four other sons being apparently equally well endowed.

Part of the cause of the confusion is that over the centuries the de Greys and the Leakes gave land to daughters and sold pieces off to outsiders and by the seventeenth century the land in Hickling was divided amongst many freeholders of whom the Stapletons were one. Among the others were Vauxes of Harrowden. The tombstone of William, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden now lies in the chancel of in the church. It was found buried in the churchyard in the 1980s. He was a devout Roman Catholic and refused to attend Church of England services, being on several occasions convicted of recusancy during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was committed to the Fleet Prison by the Privy Council for trial and afterwards tried in the Star Chamber on 15 February 1581 together with his brother in law, Sir Thomas Tresham, for harbouring the Jesuit, Edmund Campion and contempt of court. He was gaoled and fined £1,000 (£243,000 in 2013 money).

On the reformation of the monasteries the tithes belonging to Thurgarton Priory were given to Sir Thomas Gresham from whom they passed to Lionel Duckett, sometime Lord Mayor of London, and Edward Whitchurch.

The Leake family continued to hold the advowson, last using it in 1515 to appoint Ralph Babington rector. Babington’s successor, John Bailey, however, was appointed by Sir George Chaworth, who was from an old established Nottinghamshire family. Coincidentally, Sir George’s wife was a Babington. The Ingleby family must have purchased the advowson to go with the manor. They appointed a man from their own back yard, William Atkynson, as rector. They in turn must have sold it to William Fairbarne, a native of the village. His son Gervase in turn must have sold it to Thomas Beane the elder of Aslockton and his second son William. They too sold it quite quickly to Thomas Duckett, son of Sir Lionel or perhaps one of his grandsons. In the early 1600s Edmund Bardsey, rector of Hickling purchased the advowson and this is recorded in his will as being from Master John Duckett. He in due course used it to appoint first his son James and then his nephew George Fisher, who served as rector for 63 years. In1667 Edmund’s widow bequeathed the advowson to Queens’ College Cambridge, the present patrons.

Magna Carta 1215

Years of misrule by King John led to open revolt by his barons and he was forced to sit down at Runneymede and grant them a code of rights. Whilst the barons’ chief concerns were their own rights and freedoms, much of it was of benefit to the common man. Such vital rights as habeas corpus and jury trial were granted, and these have been sacrosanct ever since. Sadly, our present Tory LibDem Government, as did its New Labour predecessor, would like to take these rights away from us in order to reduce costs and to protect us from terrorists.

One area, which Magna Carta, did not cover was the right to gather firewood from the Royal Forests, but this was rectified by the Forest Charter in 1217. This allowed anyone other than a merchant to take firewood either for his own use, or to sell so much as he could carry. A freeman could also gather nuts and fruits of the forest for his own use or drive his swine through the forest.

Taxes

In 1227 the Prior of Thurgarton did not claim his right of Assize of Bread, Gallows or Tumbrell against the wishes of the Crown but the Court found in the King’s favour in 1327 and a rent of eight pounds per annum was granted to the King for the Assize of Ale. At that time the value of the Manor of Hickling to Thurgarton Priory was £24.5s.2d per annum, coming from four carucates of land at forty shillings apiece, two dovecots at twenty four shillings each, a windmill at twenty shillings with the rest coming from numerous freeholders, bondmen and cottagers.

The dovecots were a symbol of prestige and, in the days of the Plantagenets, only noblemen were allowed to own them.

The Assize of Bread and Ale was introduced in the thirteenth century in order to set standards of quality, measurement and pricing for bakers and brewers. For bread the standard measure was for a farthing loaf, which had to weigh 6lb 6 oz. It presented an established scale of ancient standing of pricing between the wheat and the bread. The assize continued in being until comparatively recent times.

In a similar way the assize regulated the price of a gallon of ale by the price of wheat, barley and oats. By the sixteenth century this uniform scale of price had become extremely unpopular and in 1531 the law was changed to allow the ale to be sold at whatever price the local magistrates should think appropriate. From ancient times the quality of the ale was assessed by officers, known as gustatores or as ale conners, who were chosen annually, by the Court Leet of each Manor. The magistrates were very strict with the brewers whom they brought before the courts regularly.

Beer or ale was both an important food source and something safe to drink. The average man would drink some five pints a day. All households needed it and only the very meanest dwellings did not have the facilities for brewing.

The brewing was done mostly by the women of the household and they did it in addition to their other household chores. It was a very slow process. First the barley had to be soaked in water for several days and then drained off and allowed to germinate. This was a tricky business. The germinated barley was then dried out with heat and ground into grist. Hot water was then added and soaked up the goodness and flavour of the mixture to create the wort, which was then drained off and herbs and yeast were added to it. When this had fermented it had become ale, which only had a useful life of a few days. At first, only the larger households would have had the facilities and the equipment for brewing. This would consist of a lead or a copper vessel and several tubs and pots. Over the centuries more and more households took up brewing. Any surplus ale was offered for sale either in the house or to callers. In years of famine the barley was needed for food and fodder and some local authorities imposed fines on people brewing their own beer.

The life of an ale wife in a town is described somewhat colourfully in the poem, The Tunninge of Elenor Brunning by John Skelton in the late fifteenth century, from which the following extracts are taken:

“And this comely dame,

I understande, her name

Is Elenor Brunninge

At home in her wonnynge;

And as men say

She dwell in Sothnay,

In a certayne stede

Besyde Lederhede.

She is a tonnishe gyb

The devil and she be syb.

But to make up my tale,

She breweth nappy ale.

And maketh thereof port sale

To travellers, to tinkers,

To sweters, to drinkers,

And of good ale drinkers,

That wyll nothynge spare,

But drynke tyll they stare

And brynge themselle bare,

With, “Now sway the mare,

And let us slay care

As wyse as an hare”.

“Good fellowship: one man drinks to keep another company.

A second end of drinking is said to be the maintenance of friendship and kindness among men.

A third end of drinking is said to be cheering their spirits, making them merry and jolly.

A fourth cause of drinking is said to be to be the putting away of cares.

A fifth end is the passing away of time

A sixth end is said to be the preventing them of that reproach which is cast on those that will in this be stricter than their neighbours”

(I am indebted to Kate Loveman of Leicester on the letters page of the Guardian for this quotation.)

Sports And Pastimes

In the reign of Edward I a law was passed banning men below the ranks of the nobility and squirearchy from taking part in any other sports than archery. This was to ensure that Edward’s bowmen honed their archery skills. It is likely that such sports as running races would have been looked at with a blind eye. In Norman days and after, handball was played using a blown pig’s up bladder but with the hand towards one’s opponents rather as in tennis today with the object of preventing them from returning it.

Stool ball was also played with the players throwing the ball at a stool with the object of hitting it. Also, there was a primitive form of bowls but at one time this was banned for the peasantry.

Indoor pastimes were essential for the long, dark evenings would include dice and singing and rustic dancing.

The Black Death

In 1346 the rat borne Black Death swept relentlessly throughout the Western world, bringing with it death, suffering and tragedy. It arrived in England borne by rats. Grandparents weeping at the sight of their dying progeny and widows and sweethearts grieving for their loved ones. Only eye witnesses can testify to the suffering and recommended reading; if you want to find out more, it can be found in the writings of Thucydides, Agliona, Boccaccio, Pepys and Albert Camus. Furthermore, it returned at regular intervals over the next two or three centuries.

Records do not exist as to how it affected the people of Hickling but undoubtedly it would have caused many deaths and blinded others. It hit Nottingham in 1349 and it is believed that some half of its population died. The initial outbreak and its successors so depleted the population that some villages were abandoned.

Eighty three lives were lost in Colston Bassett in 1603 and Nottingham was afflicted by it in 1609. Hickling’s parish registers from before 1621 have been lost but evidence from wills and the existing parish registers suggest that some families were reduced in numbers in that period. Five members of the Noble family were church wardens or swornmen between 1601 and 1607 but the last entry for that family in the parish registers was the death of John Noble in 1635. The Hopkinson family also appears to have suffered several losses.

Suggestions that the plague returned to the village in the 1660s do not appear to be supported by hearth tax returns, parish registers or wills.

Small pox and other diseases were a constant threat. Small pox could leave you disfigured or blind and measles could leave you deaf or blind and as late as the 1920s some thirty percent of its victims died. Medical assistance was in short supply. People knew to boil their water before drinking and beer was part of the staple diet. Cholera was rife. There would have been no more than one or two Doctors of Physic in Nottingham. Apothecaries would have, to a large extent, filled the gap. They would have had a wide variety of medicines, spices and poisons to kill you or cure you but in either case their remedies might do more harm than good. Letting of blood did not usually help. Extracting teeth without an anaesthetic was very painful as was any form of surgery. Barber surgeons were tradesmen not professionals.

Early in seventeenth century Hickling, those who survived to adulthood often died in their thirties or forties, many women through sheer exhaustion from the number of their pregnancies. Death in childbirth was common even up to the twentieth century. As nowadays, some couples were unable to have children and others found that their babies were weakly and few, if any of them, grew up to adulthood. With the best will in the world the doctors, whom only the rich could afford, were unable to provide much useful help. Contraception was not available and few practiced any form of restraint to the sexual urges. It is sometimes said that infant mortality was so common that people hardened their hearts towards it but my great grandmother Emily Sarah Branston, on the death aged five of her third child was so upset that she immediately abandoned her beloved family scrapbook. By contrast, of those who survived childhood, many would live to a ripe old age.

Establishment of a New Pattern Of Life After The Black Death

In Norman and Plantagenet times the monarchy, nobility and landed gentry owned most of the land and the feudal system. William the Conqueror had to quash several rebellions by the Anglo Saxon nobility after seizing power at the Battle of Hastings and punished them by confiscating their land and property redistributing among his own relations, nobles, and other supporters. These lands were held in a fief whereby the overlord granted heritable property to a vassal in return for certain obligations such as military service, the provision of fighting men and the provision of produce from the land. The lord of the manor lived in the manor house. The other inhabitants of a village were the serfs or villeins who lived in mud brick cottages, which consisted usually of one room only which was heated by a fire. The serf would also farm a strip or strips of land in his own right, the amount of land being decided by the lord of the manor. He would also be required to work on the landlord’s land or work for him in some trade such as a baker, cook or blacksmith.

Chapter Two: Seventeenth Century Hickling

By 1600 Hickling was a large village, having by the middle of the 17th century some 350 inhabitants. Of necessity it was in most ways self-sufficient. Transport and communications were slow. The wealthier members of society would have had horses or even carriages but highwaymen might rob even the most canny traveller. The roadside gallows with corpses hanging upon them were no deterrent to the serious highwayman or his fellow criminals.

When illness or misfortune struck, people may have put the blame on something which they or their communities had done but, if tragedies occurred, more than once, they would turn to their superstitions and in extreme circumstances even blame witchcraft. Two young women and their cat were hanged in Lincoln gaol for causing the deaths by their spells of two young heirs of the Earl of Rutland. Recent research has shown that the real cause was epilepsy.

Hickling’s inhabitants were self-sufficient in most things. Food was supplied by the many farmers and there would have been bread, meat and vegetables, as well as clothing and other sorts of the things needed to live a simple life. The farmers had all the help they needed to till the fields and to do any menial jobs. Imported goods were readily available in the towns. Market towns uses to have fairs where less commonly available wares could be obtained and provided sometimes all sorts of fun. The women would have had delicious recipes to make the limited variety of food more appetising and all manner of fire irons and utensils to ease the cooking. Water would have been drawn from local wells and washing done in the rivers and streams. All the larger houses had brewing facilities and there was a plenteous supply of beer. Women had control of this function and would ferment the malted barley and brew the beer which they would take out to their husbands in the fields.

People had to while away the long dark hours of winter and they congregated in the local pubs or larger houses where they sold their surplus ale. Games of dice and cards were played with more physical games being saved for the lighter evenings. Women could spin and make clothes while minding their children. Unless they were either unmarried or spinsters, women could not hold property in their own right. Tobacco had spread like wildfire since its introduction by Sir Walter Raleigh, and by the middle of the seventeenth century most men smoked. Grocers, merchants and apothecaries as well as many other shopkeepers, regardless of their usual wares, catered for their addiction.

Sports And Pastimes

When not at work, there were various forms of entertainment. The more energetic could play a rudimentary form of football with a blown up pig’s bladder, some variety of wrestling or a tug of war. Cock fighting was also popular. An Act of 1541 forbade the playing of bowls by artisans, labourers and servants on any day other Christmas day outside their gardens or orchards. Playing elsewhere would make one liable to a penalty of 6s. 8d. This law was not repealed until 1841.

The old strictures on sports were, probably, hardly thought of in a village like Hickling which had no squire.

All forms of gambling, card games such as […] and cribbage. Blind man’s buff was played by both children and adults. Children would have hide and seek, tag and many other games. Mainly because of lack of reading skills but also because of the small number of books, reading had not caught on but there would have been plenty of opportunities for singing. Festivals and feast days were celebrated enthusiastically. Fairs in local market towns provided other exciting attractions. Occasionally, strolling players would visit

Skittles was popular in the pubs around Leicester but it was played on a hooded table and was known as “Hooded Skittles” The table was leather bound with leather padded walls to the sides and back. The hood was curved like a pram and made of leather or netting. The table was about three feet high and three feet long.

The Weather

As is well documented. the winters were very cold and snow covered the soil for months at a time. Paintings of skating on the Thames and Breughel’s rustic scenes are evidence of the harshness of the winters. In Selston’s parish register “the great snow” is noted on 30 November 1658.

Lighting

Light in the dark evenings and nights would have come from candles, braziers and the flickering flames of the hearth which will have been diligently nurtured during the day. The only tallow chandler who operated in Hickling whose name has come down to us was Robert Collishaw who died in the early eighteenth century. It is not clear from his inventory whether he actually made the candles himself but it is probable that he did and in all likelihood he did. The explanation seems to be that he had retired and his son had succeeded to the business and already owned the candle house. Even so candles were available at most grocers, merchants, ironmongers and tobacconists, as well as in most villages.

At the time, John Markham of Bingham, who had substantial facilities for making candles, probably catered for most of the villages in the area. However, John Brown and Arthur Cloudsley in Melton were alternative suppliers. The candles for the altar at the church were made of wax and would have come from some distance away.

Inheritance

It is difficult to know what trades individuals carried on, as the only sources are marriage licenses, probate documents and to a lesser extent parish registers. In many cases generations of a particular family worked in the same trade. Examples of occupations found in seventeenth and early eighteenth century Hickling follow.

Yeomen and tenant farmers and labourers were too numerous to mention.

The younger sons would either be put out to apprentice to some trade or seek tenancies either within or outside the parish. The lucky ones would marry their master’s daughter when he had no sons or the daughter of a local farmer in similar circumstances. The daughters would either marry or go into service but occasionally they were apprenticed to a trade. Many younger sons and daughters never married. Even in those days some testators divided their estates more equally but this dissipated the family wealth.

Trades And Businesses

The following examples have been found up to 1740:

The word ‘taylor’ was used in its legal meaning in the documents from which this list is drawn but could refer to the maker of clothes in those days.

I have been unable to find any indication of a public house or inn in seventeenth century Hickling but most of the larger houses had copious supplies of beer and some would open their houses to all and sundry. The owners of those houses would have needed a license and in times of famine, the authorities clamped down on such drinking and brought anyone caught opening their doors without a license would quickly be brought to the beak and suitably punished. This would consist of banning them from entering a drinking house [… or habitual drunkenness]. Those […] would face the threat of distraint.

A man would want his pint after a hard day of ploughing or harrowing. A woman, likewise, coming from her domestic drudgery. As today, people sought comfort in the warmth and camaraderie of the local. Your choice of tipple was very limited. At the most important inn in a town, you could have had brandy, sack, Rhenish or the tavern’s own brew.

In 1659 Richard Allestree in “The Whole Duty of Man” identified the motives of the, “… multitude of drunkards in the world […] since an alehouse is often the room in a neighbour’s house”:

“Good fellowship: one man drinks to keep another company.

A second end of drinking is said to be the maintenance of friendship and kindness among men.

A third end of drinking is said to be cheering their spirits, making them merry and jolly.

A fourth cause of drinking is said to be to be the putting away of cares.

A fifth end is the passing away of time

A sixth end is said to be the preventing of that reproach which is cast on those that will in this be stricter than their neighbours”

(I am indebted to Kate Loveman of Leicester for this quotation.)

Most of the artisans would have traded independently but a few of the more enterprising folk would have employed specialist tradesmen. At the end of the seventeenth century John Daft at the Hall, a wealthy yeoman, was employing weavers such as Charles Wollerton to turn the yarn which his womenfolk had spun into cloth, though their relationship may have been more one of subcontractor than employee.

Sheep provided wool and flax the linen which the women toiled away at spinning. Robert Collishaw’s wife had twenty yards of linen cloth and a large amount of weaving wool when he died in 1722 and three shepherds left wills. Keeping it in the family, Edward who died in 1737 was a “stockener”. The women in John Daft’s household ran a spinning business. There were tailors for both sexes. Daniel Daft was one in 1687.

As well as spinning and weaving, the women busied themselves with cooking, brewing, dressmaking, washing and bringing up children, found time to gossip and do a little lace making on the side.

From the end of the seventeenth century and much of the following one, inventories indicate that some Hickling farmers were breeding horses but for what use whether hunting or general use is not clear.

The stocking frame was invented by William Lee of Calverton (Notts). The machine imitated the movements of hand knitters and he demonstrated the operation to Queen Elizabeth in the hope of being granted a patent but she refused on grounds of concern for the livelihoods of the knitters and the widespread unemployment that might ensue. On refusal also by James I, he transferred his operations to France in the hope of greater success but died in 1614 without being adequately rewarded for his ingenuity. The frame which he invented had eight needles but with Lee’s commercial failure his assistants drifted back from France. One, John Ashton, added a “divider” to the workings which was a major improvement.

By the end of the seventeenth century the Huguenot silk spinners had fled France, scared for fear of their lives after the St Bartholomew’s day massacre and took the industry up in a big way. They settled in the then village of Spittalfields and in 1663 The London Company of Frame Work Knitters was founded.

To start with the frame could only produce course fabric. By 1598 the machine had 20 needles and silk could now be knitted as well as wool.

Because Hickling was in a bit of a backwater the stocking frame did not reach Hickling until the 1670s when Stephen Pickard of Lambley married a widow from the village. In the few short years left to him, he fathered several children and acted as overseer of the poor.

Local Government

Village affairs were effectively run by a group known as the neighbours who appointed from among themselves, annually, an overseer of the poor and a constable. In some parishes the duties rotated among the families. Tindall of Upton’s report on the bailiff’’s attempts in 1646 to distrain one of his parishioner’s horses could have been made by the constable in “Much Ado about Nothing”.

“When Randle Leaver’s son came through the towne to warne he spent six pence on the first occasion and two shillings on the second and in connection with that and providing the neighbours with sustenance when he consulted with them.”

A few days afterwards, Tindall paid the duties which had been levied over to William Leavers for Robert Sylvester, the chief constable of Thurgarton hundred. This set Upton back a further five shillings in his expenses.

The church wardens came from the same source, (duties included) to arrange the lodging of passing travellers and to ensure that travelling paupers or vagrants and particularly poor pregnant women were rushed out of the parish by nightfall in order to make sure that they and particularly their progeny did not become a charge on the parish resources. Poverty was a major problem. In 1674 twenty of the ninety households in the village were discharged by certificate from paying hearth tax. On 17 January 1618 the church wardens and overseers of the poor were ordered by the Ecclesiastical Court to provide accommodation for a man and his wife and family who had been evicted from his house and had been forced to live in a beast house in the fields.

Between 1620 and 1640 Hickling’s neighbours came from the following families:

Of these the Gunthorpes, Smiths and Waies were variously described as gentlemen or yeomen. The Gunthorpes provided two generations of Chief Constable of South Bingham hundred. The Parlebys were bakers. a very important trade in those days and highly respected. The others were yeomen or tenant farmers. The Gills moved over from Old Dalby or Dalby on the Wolds as it was then known. Edward Collishaw came to Hickling in the first twenty years of the seventeenth century. He may have married an heiress inherited it or, less likely, bought his land in Hickling. He may have been born in Plumtree.

It is unfortunate that the names of very few of the constables and overseers have come down to us. The parish registers and bishops’ transcripts preserve the names of the church wardens for much of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

People used to refer to their village as the town.

Hickling was not on a thoroughfare and would not have been troubled with all that many travellers but, if any came, some householder would have had to give up or more probably share his or her bed.

Throughout the seventeenth century the Church, which was very powerful in those days, kept a strict attitude to immoral behaviour. The Vicar of Mansfield and his strong minded church was not tolerated either. William Robinson of Retford was fined six pence for attending a sermon by his brother, John, who was pastor to the Pilgrim Fathers. They were so severely oppressed that they fled first to the Netherlands and then to America. Richard Southworth, a yeoman from Retford, moved with his young family to Mansfield to set up afresh and later became church warden there. Some were even indicted for repairing the churchyard on the Sabbath day. Later in the century these pressures eased, though Quakers continued to be persecuted and lists of non-attenders at church survive.

Being in a backwater, Hickling would not have been greatly exposed to the Civil War, though legend has it that there was a battle on the Standard. The parish would, however, have been required to provide a few soldiers to assist the Republican cause in Nottingham and external food supplies may have been [scarce]. Particularly in the earlier part of the seventeenth century and before that, the church exercised strict controls on the morality of its flock. Apart from such matters as drunkenness and sexual immorality, it strongly disapproved of failure to observe the sabbath day and marrying at the wrong church.

Village Childhood

The lack of knowledge of, or interest in, contraception, high infant mortality and the desire to have successors to take over the family business and to look after them if they grew old or feeble, and some people did have long lives, made them have many children. Wives produced children year in year out until they died or were rescued by the menopause. They had to harden their hearts to the frequent deaths of their beloved offspring, though this did not mean that they suffered any less than we do when tragedy struck. This is poignantly expressed in a stained glass window of Bunny church.

My great grandmother, Emily Branston, when her son, Godfrey, died aged five, stopped keeping her scrapbook of newspaper cuttings which described all the lavish civic banquets and society weddings which she attended. Those who were not blessed with children would have been as jealous as some of us today but they had to harden their hearts and enjoy their numerous nephews and nieces. The grandparents would be in charge during the day and from a fairly young age the children would be encouraged to help in the home or at the farm or the father’s place of business. Boys were forever boys and girls were forever girls and they would play, girls with their rag dolls and boys with their toy swords and toy guns. and sometimes get up to mischief. Then they would have smarted with the sensation caused by the meeting of Granny’s swarthy hand or Granddad’s knobbly walking stick.

From the day that they were born babies were heavily swaddled and either lying in their cradles when their more earthly needs were not being attended to while rattling their rattle or string of beads. Mummy or Granny, or was she Nanna? would sing lullabies or gently rock them. As soon as they could crawl, they were dressed, still warmly, in smocks whichever gender they were and girls wore bonnets. They wore no nappies and would simply be followed around with a mop and a scoop, for there were no carpets in their houses. Doting Grandmas and Grandpas would endlessly recite Nursery Rhymes such as “Humpty Dumpty”. “Humpty Dumpty” was a drink made of brandy boiled in ale and satirical cartoonists like George Cruikshank used him for poking fun at their victims. “Hey diddle diddle the cat and the fiddle” was another favourite but they may have said “Hey, nonny nonny no” as in Shakespearian days. To suit the palate “Pease Pudding hot pease pudding cold ” and “Christmas is coming, the geese are getting fat” would have been popular.

The Ecclesiastical Court and its Treatment of Ordinary People

Instances of court appearances of local people follow.

1587: William Atkinson, parson, Thomas Noble and William Howitt, church wardens and John Warde, curate, came before the court by Thomas Jesson and Ralph Pecke who were perhaps constable and overseer.

“We present Mr Fearbarne for that he did not receive the Communion this last Easter for that he and the parson were not friends

The lead of our church is something in decay but we appointed a workman to mend ye same.

Our parishioners did ring corfew upon Alseynte evening but who they were we do not perfectly knowe”

(ringing the bells on All Saints Eve (Halloween) was considered pagan)

12 December 1601. Edward Bloode and Jane Randall of Hickling were accused of marrying at the wrong time. Edward admitted that he was married on 1 December by Mr Warde, the Curate of Hickling, and that there were present one Stephenson, Robert Dafte, George Dafte, Thomas Musson, Thomas Harris and Thomas Dafte. He was automatically excommunicated and afterwards absolved and dismissed.

3 February 1613 Richard Waies and John Musson, the then church wardens were charged that “theie suffer the churche porche to be unrepaired and the seates are not decentlie kepte”.

29 October 1613. The case of Alice Stubbin alias Rustat v William Stubinge was heard. Alice was claiming non payment of a legacy. Each side was represented by an advocate, Mr Gymley for the plaintiff and Mr Brandreth for the defence.

The case was adjourned until the following Thursday and the defendant was warned to attend and produce the inventory of Henry Stubbinge. William Stubbinge failed to attend on 11 and 26 November but appeared on 10 December but without the inventory and contested the allegation.

On 10 February the judge summed up. The plaintiff had asked for an adjournment until a fortnight the following Saturday to prove her case. Claim his expenses.

On 25 June 1614 William Walker of Upper Broughton was charged with

“usinge himselfe disorderlie in the chuche porche and church yarde by givinge threateninge and revilinge speach to William Shawe uppon the Sabbath daye”

In 1619 Helen Burton of Mansfield was charged with sorcery. She could not be met with but was cited as “vile et media” and excommunicated.

On 12 January 1618 the church wardens and overseer of the poor of Hickling were ordered to provide for a poor man and his wife and children who had been turned out of his house and had since lived in a beast house.

On 15 January 1621 Agnes Dickenson of Owthorpe was presented for usury and “that she taketh about tenne pounds in the Hundred” Elizabeth Peller was charged with a similar crime.

On 2 June 1621 John Gervis of Upper Broughton was charged with swearing in the chancel of the church there. He admitted the offence and did use some “unfitte speeches”. He was ordered to do penance.

23 March 1623 Francis Daft appeared for his father, Thomas, a Hickling yeoman, and paid into the court two pence due to the parish clerk for half a year’s tithes on one part of a dwelling house in which he maintained.

On 7 November 1623 Thomas Litster, Margery Frauncis and William Hewkesley of Upper Broughton were charged with “going to the boys at Wisall”

George Daft’s (died c 1613) third son, Thomas, was clearly an argumentative type and George’s will provides that “if the said Thomas my sonne shall or could ere hereafter kikke moleste or sue any of his brothers or sisters for or concerning my houses or lands by this my last will and testament unto them or any one of them given or bequeathed, then this present guift or disposing of the said messuage, dwellinge house, close oxgange of land meddowes and pastures and other the guift before mentioned unto the said Thomas Dafte shall forthwith cease and become void”. While this warning in his father’s will appears to have worked, his combative nature was still in evidence in 1624 when the then church wardens with the blessing of the rector, Dr Edmund Bardsey, took him before the Archdeaconry court as follows: “Thomas Dafte the elder, one of the churchwardens of Hickling, was lately presented by them for divers defaults and misdemeanours committed within the township and church of Hickling, before ‘your worship’; they have not yet had sufficient reformation worthy of his offence; therefore, with the voice and consent of Mr Doctor Bardsey (parson of Hickling) they humbly pray that the said Thomas Dafte the elder, who was presented for his perverse dealings and his railing and slanderous speeches and for his reviling, scornful and reproachful wordes with the church, and for other misdemeanours, may have his submission or penance enjoined on him without delay, to be done within the said church of Hickling, seeing that he has not cleared himself”.

12 June 1624. William Musson, John Peele, Robert Jesson and Elizabeth the daughter of John Browne were taken to court for not coming to church at the appointment of the minister to be catechised. They were dismissed with a warning.

8 June 1669. Samuel Atkins was charged with teaching schools without a licence but he had already gone away to another part of the country

17 May 1670. Robert Smith of Hickling and Elizabeth, his wife, charged with having had a clandestine marriage. They admitted that they had been married without banns or a licence at Stonesby where Elizabeth then resided.

22 November 1670. John Caunt of Hickling and Dorothy his wife admitted at the Court that they had been married at Hose on 26 December last without a licence or banns.

Amazingly the Church of England has hardly relaxed its rules as to when it would marry you ever since. It is only from today, 1 October 2008, that it will allow you to marry in any church of any parish where one of the couple has lived for six months or even their parents or grandparents have lived. If not, you have to go through the hassle of obtaining a licence.

Chapter Three: Eighteenth Century Hickling

Thoroton, writing in the 1770s, noted that the Lordship of Hickling contained upwards of 2,000 acres which were owned by a Mr Londel and others which were enclosed about fifteen years ago. He also said that Hickling lies in ‘a very miry pat of the county’ and consists of about 70 dwellings.

In 1707 the villagers of Hickling were ordered to assist those of Colston Bassett in scouring the River Smite but refused to do so. They were taken to court over this but won their case.

In many ways life would have become easier in the eighteenth century. Religious dissenters were tolerated. There were no civil wars. The Plague ceased to be such a threat. Infant mortality dropped and large numbers of children survived to adulthood. While this would have saved families much distress, the explosion of the population created an excess of labour and there were not enough jobs around. This meant that wages would have been low. Several lads migrated to the towns where they could obtain work or exploit their trades but living conditions were more cramped and for the less well off the slums were a living hell apart from the strong neighbourship bonds. Cleverer boys could prosper. Richard Smith became an attorney and Stephen Daft a tanner.

The Enclosures Acts gave rise to our familiar hedges and ditches. They came about because of pressure from farmers who believed that, if all their land were in one area instead of the strip system, they could farm more efficiently. They came to Hickling in 1776. Hedges were planted and ditches dug extensively to delineate boundaries. For a short time this brought employment for the labourers. Later in the century the Industrial Revolution provided poorly paid employment in abundance and poverty, while remaining a severe problem for them, migrated from the villages to the towns. Tuberculosis became endemic in the slum dwellings of the workforce in the towns and diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, scarlet fever, diphtheria, measles and mumps.

Hickling remained almost fully involved in agriculture and self-sufficient in all the central trades. Unsurpisingly, framework knitting provided profitable employment for many local people, both male and female. It being a major industry in the area. Frames were purchased and hired out by the better off people to some of their neighbours and were regarded as a sound investment. Elizabeth Daft, an elderly spinster, left two frames in her 1798 will and mentioned Ann March, Jack Moulds and Ann Morris or Hickling and Ann Barnett of Long Clawson as knitters.

More and more people turned to the frames for their bread and butter. The only names to come down to us from the first half of the eighteenth century are Edward Collishaw and a relative of his who had moved to Nottingham and Paul Shipman.

While the industry had spread massively throughout the Midlands, little had happened to improve the mechanisms of the frame until 1758 when Jebediah Strutt introduced an innovation which produced what became known as the “The Derby Rib”. The Industrial Revolution and Richard Arkwright’s spinning machine quickly reduced the former prosperity of the knitters to abject poverty within twenty years. Their unsurprising reaction was Luddism and factories and mills were turned to smouldering ashes in a matter of hours. Davison and Hawksly’s Arnold (Nottingham) Mill briefly burgeoned and boomed, even feeding the poverty stricken in the famine of 1800. Their copper pennies and shillings are a token of the benevolence of rich men imbued with the ideals of the French Revolution and a devout wish to alleviate poverty.

Hickling remained very much isolated from the outside world other than the regular visits to local markets and the towns where they were held. Sometimes there would be a demand for the village to provide a man or two as cannon fodder for the militia or an unlucky lad like John Granger of Smisby would be press-ganged into the Navy. Even so. it could not stay totally oblivious of the financial shenanigans of the distant city of London.

In the early part of the century, there was a trader in bear skins and may be this story is apocryphal but in all probability it was true. He was so quick on the draw that they said that he sold the skins before they had come off the bears’ backs, giving rise to the term ‘”bear” for a short seller.

For Hickling, the 1790s saw the building of the Grantham Canal. [Coll?]ashaw, a grazier, whose land was next to the Canal set up additionally as a coal merchant. This business flourished for many years under himself, his widow, son and grandson. He also purchased two shares in the Grantham Canal Navigation Company.

Chapter Four: Nineteenth Century Hickling

There were two pubs in Hickling in 1832, the well established Plough, run by George Hives, who was also a corn dealer. By 1856 there were four public houses, The Plough, The Navigation, The Wheatsheaf and The Wheel. The Navigation had a wharf by the Canal and was next door to the Plough. It was first licensed in [1844 by J Shipman] a farmer farming 119 acres, but by 1853 he was landlord of the Navigation and a wharfinger. Inevitably the Canal brought with it an increased risk of crime and for that reason the village had its own policeman.

At the beginning of the period the secluded agricultural population […]. Knitters struggled on for a few more years but gradually fell into unemployment. For them the canal came as a Godsend, as it provided new opportunities for employment.

The six month old Frederick Maltby, the son of a farmer, was to have an eventful life. At an early age he was taken over to America, where he was adopted by the Warner family. He ended up wealthy and became governor of his State.and is commemorated by the cherry tree opposite the [Church] porch.

In the 1851 census eight surnames survived from the seventeenth century: Daft, Faulks, Hopkinson, Mann and Marriott from the beginning. Edward Collishaw and Paul Hardy arrived soon after. When the Morrises arrived is unclear. It is said that folk in those times married people within a five mile radius of where they lived. This is borne out by wills and marriage licenses of the period. Occasionally, particularly when the couple came from different parishes, they would make a day of it and marry in Nottingham. There were few fashionable marriages which took place in Hickling and such as there were related to the Fisher family.

*[Families could usually t the situation was usually more blurred with many being a bit of each. In the early years of the century, Thomas Cullen of Upton who had eight children was described sometimes as one and sometimes as the other.]

Land was still farmed in the strip system with crops being strictly rotated. Except in the case of more wealthy land owners who measured their land in acres, the commonest measurement was the oxgang which was the amount a man with an ox could plough in one day. Some land had already been enclosed and would probably have been surrounded by hedges. These were called closes and were measured in acres as best could be estimated. The will of John Musson makes it possible to see a similar system in operation. On the wide verges of a mud track isolated cows were tethered to trees. In the towns, more wealthy families would keep a cow on their plots of land.

In the 1970s only seven surnames from the 1851 census survived. Collishaw, Faulks, Herd, Marriott, Murden, Parkes and Woolley. As noted, below, the 1851 populace nearly all came from Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and neighbouring counties. Perhaps surprisingly, some of the farmers came from further afield. Samuel Marshall came from Leicester, Charles Oxby from Carlton le Moorland, Northampton. More interestingly, a labourer, William Morris’s, sixty year old wife, Mary, is shown in 1851 as having been born in Athlone. It seems likely that she was the daughter of an Irish navvy, but the position is probably more complicated because their 25 year old daughter was born in Dublin. Other wives had come from a considerable distance; Elizabeth, the wife of John Hopkinson, a grocer was born in Cumberland; Hannah Starbuck, another labourer’s wife hailed from Wisbech.

As time went by, what was new became the norm and the character of the village changed. A Wesleyan Chapel was built in 1804 to be replaced by the present building in 1848.

The influx of people brought more awareness of the messages spread by the so-called dissenters. There arose a distinct divide between church and chapel, which was still noticeable three quarters of the way through the twentieth century. The larger population in 1910 shows that their number at the beginning of that book* was not markedly greater than those seventy years later.

There had been some sort of schooling in Hickling since before records began.

1730 Robert Mann left five pounds, the interest on which was to be paid to t61*. There appears to have been no dedicated school house until the present Village Hall, formerly the Church Hall, was built in 1876. A board of school trustees was well established at that time.

[Between 1861 and 1871]*

By 1851 medical knowledge had improved very little. Laughing gas had been discovered but its proponents had been derided and laughed off the scene. Much suffering under the surgeon’s knife and in the dentist’s chair could have been saved. An Austrian doctor had instituted a more hygienic method of delivering babies and the mortality rate of mothers in his ward showed significant reduction. His colleagues showed no inclination to follow his example. Florence Nightingale had brought much improved nursing practices to the casualties of the Crimean War and beer was cheap and plenteous.

The advent of the canal would have made coal much more affordable. Tallow chandlers appear to have largely disappeared from the scene and oil lamps now provided much needed light. Gas lighting had reached the towns.

Travelling could be hazardous. The roads were better and Mcadamised tar had begun to be introduced. Mail coaches and other forms of wheeled transport quite frequently lost wheels or broke down in other ways. Horses sometimes went lame or just died of exhaustion.

My three times great Grandfather, James Smith, a joiner and Baptist and lay preacher, travelled around on his nag and sometimes his grandson, James Granger, used to sit behind him adding to the weight his steed had to bear. Later, he was entrusted with missions by his grandfather and he recounted on one occasion being sent to Kirkby Woodhouse with the half yearly annuity of an elderly former house keeper of his deceased great uncle. He had started early because of the long distance he had to go and the road was empty to begin with. He later recalled how nervous he had been when a stranger was walking in the other direction. Fortunately, he was harmless.

*[age old methods of ener in the century …]

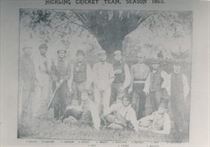

Hickling had a cricket team and football was soon to become popular.

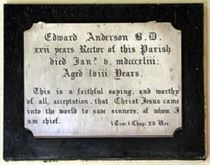

Six people are described as paupers in the 1851 census and Hickling’s oldest inhabitant, a ninety one year old lady was on Parish relief. Others might already have been dispatched to the nearest workhouse. A poor rate […] households were discharged by certificate from paying hearth tax. The overseer of the poor had to raise the tax from members of the village and occasionally those departing this life would salve their consciences by leaving a small legacy to be distributed amongst the poor. A poor box was placed in the church in 1688 by the then church wardens, Henry Faux who married Elizabeth Stephenson at Hickling on 4 June 1683 and Richard Brown. whose initials appear on it. Andersons Charity provided bread for the poor from the 1840s. In 1928 nine people received loaves and in 1934 sixteen, reducing to thirteen in 1939 who each received three loaves. In 1955 there were twelve recipients and finally in 1967 six.

Nineteenth Century Childhood

Little had changed from earlier times, babies were well clad and boys tended to be naughtier than girls. More families could afford a nanny. Toys became more sophisticated. Musical boxes charmed babies to sleep. Much to the chagrin of some, schooling became nigh on compulsory and education became more formal. Endless learning by rote and recitals of tables were enough to deter most children. If you misbehaved you had the prospect of one hundred lines or five hundred lines or “I must not ……….”. Better off families dressed their children beautifully but they did not look forward to their comeuppance when they erred from the straight and narrow.

New Nursery Rhymes were added to the repertoire as more public figures were ridiculed. “The Grand old Duke of York” was Prince Francis Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, the second son of George II. He led a painstakingly slowly prepared attack on the French Republic’s conquests on Flanders and the hill was the city of Cassell which is on a hill about 176 feet high. Other people have suggested two locations in Suffolk near the Arm barracks but they do not seem to fit. Napoleon was the bogey man and is ridiculed in “Boney was a Warrior”

Chapter Five: War

What better way to end this section than to deal with war.

At the turn of the century, Wellington was in the midst of his campaigns against Napoleon. In 1812 we were to have Waterloo. For a quarter of a century we had peace. The brutalities of war had sunk into our psyches but, as soon as a generation of politicians with no direct experience of war takes over the reins of power, all is forgotten and the lust for glory returns. While wars were being waged in such distant places as India, they barely reached the pages of the Newspapers. And so came the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade so memorably recounted by Alfred Lord Tennison. The Franco Prussian War did not concern us especially with Queen Victoria’s son in law, Freidrich, being heir to the Prussian throne.

The century ended with the Boer War. An unnecessary war and a gruelling one, with the British forces being besieged in Mafeking and fought at Ladysmith. Many lives were lost. Others were injured, some harpooned by Zulu spears. The effect of it on the common soldier is epitomised by Rudyard Kipling;s words for the marching song: “Boots, boots, boots, marching up and down again.”

Winston Churchill got a taste of war, a most important experience for a wartime Prime Minister. Baden-Powell got his ideas for the Boy Scout Movement.

Within a mere fourteen years of 1900, we were embroiled in the bloodiest war of all, the first off two great wars to dominate the 20th century.

We were soon singing cheerily but warily in the belief that it would be all over by Christmas:

“Brother Bertie went away, to do his bit the other day,

With a smile on his lips and his lieutenant’ pips on his shoulder bright and gay.

As the train moved away, he said: Remember me to all the girls

And then he wagged his paw and went away to war, shouting out these pathetic words

Good bye-ee, good bye-ee, wipe the tears, baby dear, from your eye-ee,

Though it’s hard to part you know, I’ll be tickled to death to go.

Don’t cry-ee, don’t sigh-ee, there’s a silver lining in the sky-ee,

Bonsoir old thing, Cheerio, Chin chin, napoo, toodle-oo, good by-ee”

And soon:

“The bells of hell went ting-a-ling-a-ling for you but not for me,

and the little devils went sing-a-ling for you and not for me,

Oh, death where is thy sting-a-ling-a-ling,

Oh grave thy victory,

the bells of hell go ting-a-ling-a-ling for you but not for me”

And men were matching to the tune of:

“Goodbye, Dolly, I must leave you,

Though it breaks my heart to go,

Something tells me that I am needed,

At the front to fight the foe,

See- the boys in blue are marching, And I can no longer stay

Hark – I hear the bugle calling.

Goodbye Dolly Grey”.

Men in their hundreds of thousands died in the appalling conditions of the trenches. More and more men were being sent to Flanders and the Somme as cannon fodder. Many showed immense bravery, the few who waivered and deserted were mercilessly shot at dawn, even though they were shell shocked or had just been spattered with their best pal’s blood guts and brains For some, a brief respite from “Wipers” would find solace in the arms of “Sweet Lilli Marleine” and they would come home for short leave. The more fortunate were sent home with minor injuries and would have a more extensive period of recuperation.

For those at home, the daily fear of receiving a knock on the door and a telegram would have been as agonising as the fond farewells.

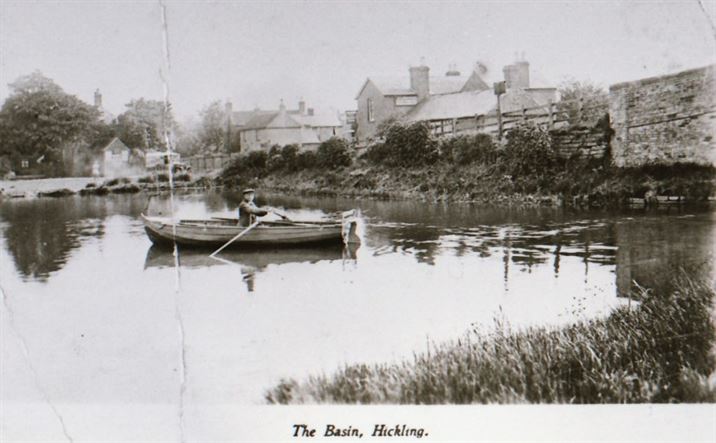

Hickling lost seven men who were killed in the war and Stumpy Watchorne lost a leg. A photo of him, standing up on his boat on the Basin, hangs in the Villagers’ bar at the Plough.

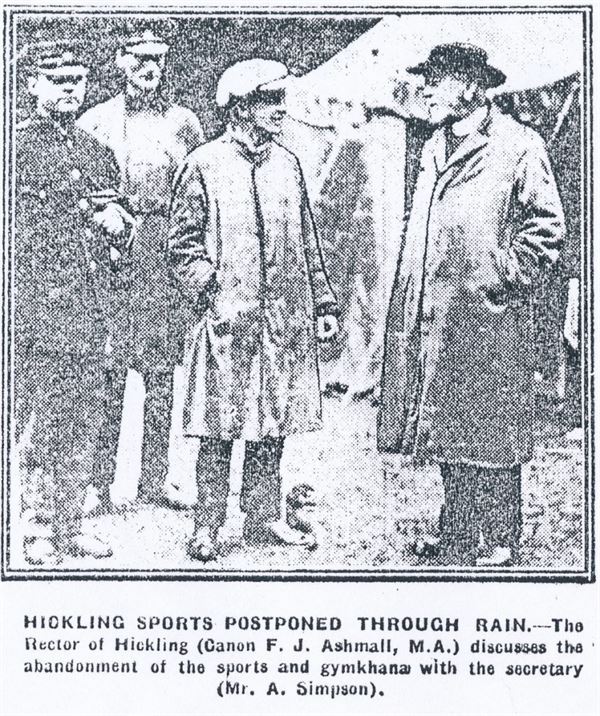

It is impossible in retrospect to express the sentiments of the village people in those days but we are indeed fortunate to have the writings of Francis Ashmall, the Rector of those days whose words so eloquently express the feelings of ordinary people of that age. These are to be found in the final pages of this book.

The vengeance meted out to the Germans at Versailles was too harsh. They were deprived of their industrial power base in the Alsace and the reparations which they were forced to pay were crippling and led to recession and demotivation and in due course Hitler came to power. The consequences were horrific.

Soldiers sang as they marched along:

“Hitler has only got one ball,,

Goering has two but very small,

Himmler is very similar.

And poor old Goebbels has none at all”.

… and many variants of this.

For forty years, we had the cold war and when we thought we were past war, we had Iraq and Afghanistan.

“When will they ever learn”

Chapter Six: The Church and Churchyard

Early History.

Domesday Book carries no record of Hickling having had a church but there must have been a place of worship ever since the Vikings came in their high prowed ships and wielded their battle axes. During the course of their rampage, they pillaged the land and they must have conquered such places. Otherwise, our neighbouring villages would not be named Harby, Granby or Wartnaby. Anglo Saxon and Viking relics have been found all over the area. The sarcophagus which now lies in the porch bears both pagan and Christian symbols in the hope of appeasing whichever God he would find presiding at the Judgement Day. This is evidence of a Viking settlement.

*Diligent monks would have been welcomed into the villages by the more devout-natured, trusting the missionary monks who would gradually weadle their way in [despite] their, at times, fearsome menfolk. Another sarcophagus can be found built on to the tower. This one however had a simple Cross, though this more likely dates back to Anglo Saxon days.

According to pre-reformation wills, Hickling church was dedicated to St Wilfrid. Orton’s Thesaurus of 1763 says that “it comprises a nave, North and South aisles, South porch, chancel and Western tower. The fabric measures internally 21ft 2″, in length of nave 47ft 8″, width of nave 21ft 2’”, width of North aisle 10ft, width of South aisle 18ft 9”, length of chancel 41ft 3, “width 15ft 2”. The tower is 10ft 9″ square inside.

The only differences today are that the chancel is Victorian Gothic rather than Early English, the tower looks as though it was built one hundred and forty years ago, which it was, and the weather vane has recently been moved from the centre to the side of the roof of the tower. The clock will have looked different, having been replaced in 1890 by one made by Smiths of Derby. In 1835, Robert Story, a Yorkshire man of peasant stock wrote

“Encircled by trees in the Sabbath’s calm smile

The church of our fathers, how meekly lies

Oh villagers, gaze on the hallowed pile

It was dear to their hearts, it was raised by their hands

The love’s not the place where they worshiped their God

The love’s not the ground where their ashes repose

Dear even the daisy which blooms on the sod

Dear is the dust out of which it arose”

A “sketch” of the church, which probably dates back to about 1900, is:

“The nave arcade is Early English work of four bays, the pointed arches of to orders of chamfers (bevels), being supported by octagonal pillars with moulded caps and bases.

“The clerestory contains four plain oblong windows of three lights each on either side. The roof, formerly high pitched as indicated on the East wall of the tower, is constructed of massive timbers and covered with lead which on 1 November 1887 was stripped off during a heavy Southerly gale. The aisles, which are of the Early English period, and the supported diagonal buttresses are built of local limestone in narrow courses except the buttresses and East wall of the South aisle which appear to have been rebuilt of a yellowish stone in 1736. The roofs of low pitch are covered with lead. The West wall of the North aisle is partitioned off for use as a vestry. At this end is a plain oak chest on the front of which the date 1815 is cut. The Eastern side is occupied by an organ. The wall which carries two Decorated windows being plastered in this aisle except for a small slab of stone which projects from the South east aisle and which may be the Paschal for the Virgin or patron saint referred to by Stretton”.

Stretton wrote:

“The plain rectangular font is of about the date of the Reformation when the old fonts were restored. The chancel is spacious and has two light windows an a three light East window with O G heads and tracery but the latter is bricked up for the admission of a modern altar piece of great merit. The railing, steps and stones of consequences with border inscriptions worn out are good and neat. In the chancel, lying on the floor, is a singularly curious Danish grave stone, coffin shaped and roofed which probably has been in the lid of a stone coffin. It was dug up in the churchyard many years since, in making a grave. On the edges it is about four or five inches thick and in that part it is eighteen inches wide. Over the breast is a cross patee surmounted by a shaft running from the bottom to he centre, the sides, top an ends are divided into compartments with runic knots and allegorical figures like the ancient crosses still standing in some church yards in this country”.

Memorials and Features.

The Bryceson organ was installed in 1840 and overhauled in 1936 and again in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Over the last century virtually nothing has even changed its position in the church. The chest has moved from the North aisle to in front of the back pews on the left facing the altar. The sarcophagus was stood on its end near the Paschal stone in the South aisle and most regrettably this caused it to crack top to bottom. This has now been expertly repaired but the crack is all too plain to see. It now lies on the North side of the chancel between the choir stalls and the altar. Opposite it lies the Vaux tomb stone which commemorates the death of Baron Vaux of Harrowden but more of this later.

This was William Vaux, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden. He was a Catholic and was several times convicted of recusancy in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. He was committed to Fleet Prison by the Privy Council and tried in the Star Chamber in 1581 along with Sir Thomas Tresham for harbouring the Jesuit, Edward Campion, and contempt of Court. He was sent to prison and fined £1,000. He died in 1595.

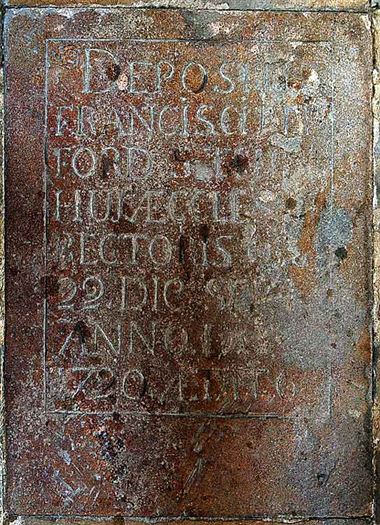

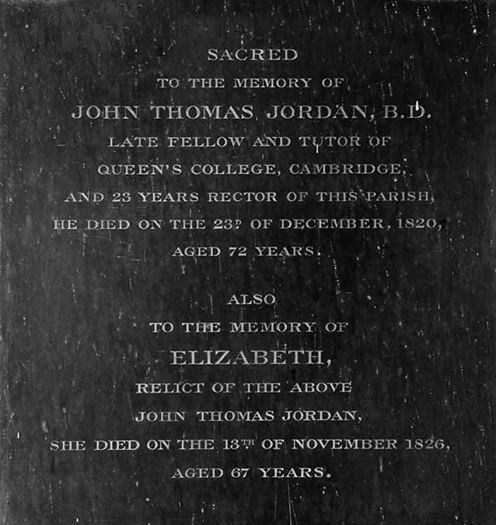

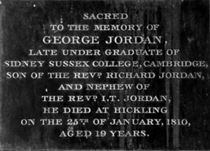

On either side of the chancel are the memorials to eighteenth and nineteenth century rectors and a plaque commemorating the rebuilding of the chancel. There is a piscina on the South side of the chancel in front of the altar and another one in the South aisle, giving the impression with its Paschal Stone of having once been a private chapel. On the floor, being worn away by feet are the Babington brass and the worn grave stones of Francis Bedford and Richard Coke, respectively rector and curate who died in 1716 and 1724.

The Royal Coats of Arms and that of Queens’ College, Cambridge in the tower have recently been restored thanks to the efforts of Commander Rawlinson, lately deceased, and Rosemary, is wife. They are now resplendent in their glory. Would that a more prominent place could be found for them in order to show off their true magnificence.

A brass plaque to Primrose March who died in 1934 adorns the wall of the South aisle. She was killed by a vehicle on the A606.

At the North end of the main church door, a place has been partitioned off to form a kitchen and a separate disabled toilet. A table stands in front of it for serving coffee and biscuits and on high days and holidays, wine. The font is further back. It dates back to Richard II’s reign, 1337-1399 but it was restored in the 1840s.

The knob on the top of the font will have been made by the village carpenter in the first half of the seventeenth century. This may have been Thomas Wilson.

The pews are Victorian and regrettably those in the South aisle have recently been removed. A letter to a newspaper by a Mr E W Bell who was a boy in the 1870s recalls a swarm of bees flying in during a service and landing on a maiden lady’s hat. She had the peace of mind to take her hat off and set it down beside her and continued singing the hymn unperturbed. The pew was a box pew and this dates the pews back to about 1880. The box pews had probably been fitted in the seventeenth century. Prior to that the wealthier parishioners provided their own seats. Harry Huston, who died in 1587, left two shillings in his will for the repairing or remaking his desk in the church.

On either side of the bridal path stand the church wardens’ wands. A rather fanciful notion of Peter Harrison’s. It is hard to imagine swarthy wardens of yore waving these fairy wands. It was difficult for me to hold it while propelling my wheel chair. There is an old coffer in front of the vestry. This probably dates back to the 17th century and may also have been made by Thomas Wilson.

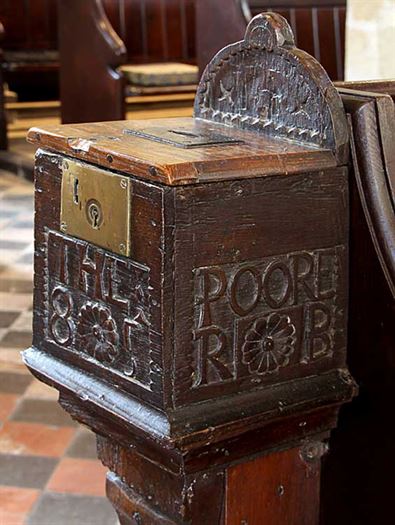

The poor box is dated 1686 and bears the initials HF and RB. These initials on stand for Richard Blower, who was one of the church wardens that year and a carpenter by trade, and Henry Faulks, who was the only person in the village with those initials.

In the tower hangs the list of legacies to the church and towards the provision of a schoolmaster. It is surprising that of all the various bequests only William Westby’s ten pound legacy survives of the perhaps £300 overall. Has there been a massive fraud here?

Above is the belfry, with bats to boot, and there resides the pride of bells. In 1935 the clashing of bells was too much for the delicate ears of either the Rev or Mrs Foster and the louvres in the belfry were half boarded up. In the 1980s and 1990s a concerted effort at fund raising by a dedicated team of bell ringers and their supporters secured the money to increase the number of bells to a full peel. This funding also paid for a new bell frame. The bells are:-