Henry (Rouse) Garrett: New Zealand’s first Bushranger and ‘The Gentleman Highwayman’.

Henry Rouse was baptised in Bottesford, Leicestershire in March 1818; his parents were Thomas and Catherine Rouse. The family later moved to nearby Hose and it is the village of Hose which is generally referred to as his place of origin. Said to have had a troubled childhood which included the early death of his mother he was variously described on the one hand as tall, handsome and charismatic; gentlemanly with firm morals; highly intelligent and well-learned and, on the other hand; a violent, bitter, vengeful and unscrupulous cur – he seems always to have divided opinion. Henry (Rouse) Garrett would become notorious nationally in three different countries – in England, in Australia and in New Zealand.

- He was known by a number of aliases; Henry Beresford Garrett, Garratt, Codrington Revingston, Long Harry, Harry, William Green (although whether all these names refer to just one man and that man being Henry Rouse is unclear).

Although there is no direct evidence of Henry Rouse in Hickling itself, links have emerged which led to an exploration of his history:

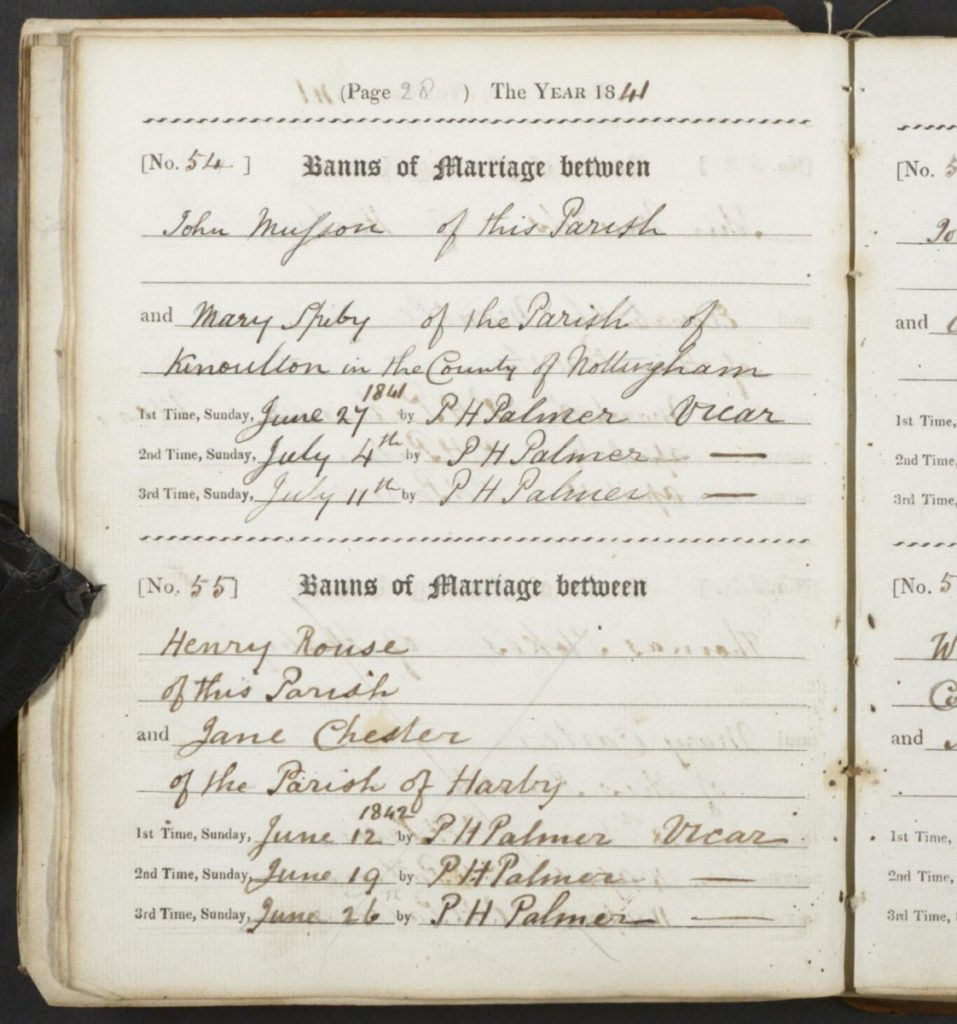

- It appears that Henry Rouse was due to marry Jane Chester in 1842 although the marriage doesn’t seem to have gone ahead (Rouse is listed as single when he is deported in 1845); Jane Chester is almost certainly listed in Hickling in the 1841 census in the household of Robert Gill (grocer) but no trace has been found of her after 1842.

- Henry Rouse and Samuel Morrison were part of a gang said to have terrorised the area in the late 1830s and early 1840s; they were both eventually convicted and deported to Australia in 1845. Samuel Morrison’s brother, James Morrison and his family lived in Hickling at about this time (Jane Morrison died here in 1843) and James Morrison was himself deported to Australia in 1852.

- Given his notoriety across the Vale of Belvoir before his deportation it seems unlikely that Henry Rouse was unknown in Hickling.

- Lastly, Hickling born cousins Joseph and Mark Starbuck emigrated to Australia in 1849 on the ill-fated James T Foord (cholera ship). Joseph Starbuck settled in the Melbourne area of Australia and Mark Starbuck initially settled nearby but moved on to the Dunedin area of New Zealand in 1863; both areas were seriously affected by the activities of the bushranger, Henry (Rouse) Garrett.

Timeline: 1818-1845 (England)

(see also lineage, below)

(records of most of Henry Rouse’s activities are dependent on news reports which vary in quality, particularly those written after his death)

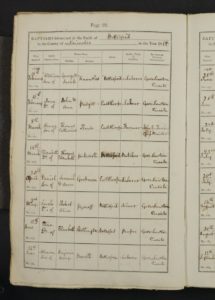

- Henry Rouse is baptised in Bottesford, Leics in March 1818 – parents are recorded as Thomas and Catherine Rouse. The family is also recorded in Easthorpe which is a small hamlet next to Bottesford.

- He is the youngest of 4 children:

- Ann baptised in Bottesford, 13th November 1814

- James born 1816

- Thomas born 1817

- Henry born 1818

- He is the youngest of 4 children:

- Later in life, Henry Rouse described his father as a violent drunk; although quite possibly correct, his later accounts aren’t always reliable.

- 1821: His mother, Catherine, dies in Bottesford in 1821.

- Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett by David Green; “Catherine Rouse died in 1821, and the family lived with a grandmother until Thomas’s remarriage in 1832. In later life Henry was bitter because his father had neglected him.”

- 1832: His father marries again in 1832; Thomas Rouse (widower) 6th November 1832 to Elizabeth Henton age 49 (both of Hose) – marriage license obtained.

- 18th January 1839: Nottingham Review – theft of turnips by Henry Rouse of Loughborough (unlikely to be the same Henry Rouse)

- Various accounts of his activities at this time:

- At some point he trains as a cooper and this is referenced as his trade throughout his life.

- A letter to the papers in 1855 claims that he was away at sea for some years and that he was a pirate (robbery and murder).

- In 1853 a news report about his sister, Ann Rouse, says that she reported him to have been a soldier in Canada for some years.

- His arrest in 1845 also describes as being a soldier in Leics at that time.

- 1841 Census: recorded in his father’s household in Hose – age 20, no profession listed

- 1842 (see lineage, below): There are records of Banns being read in 1842 for Henry Rouse (of Hose) and Jane Chester (of Harby) in both parishes; whilst Rouse is recorded in the Hose and Harby area at this time, his deportation records describe him as ‘single’.

- There is no marriage record – perhaps it didn’t proceed.

- Jane Chester may be listed in Hickling in the 1841 census but there are no further records for her.

- There is no sign that she followed Rouse to Australia.

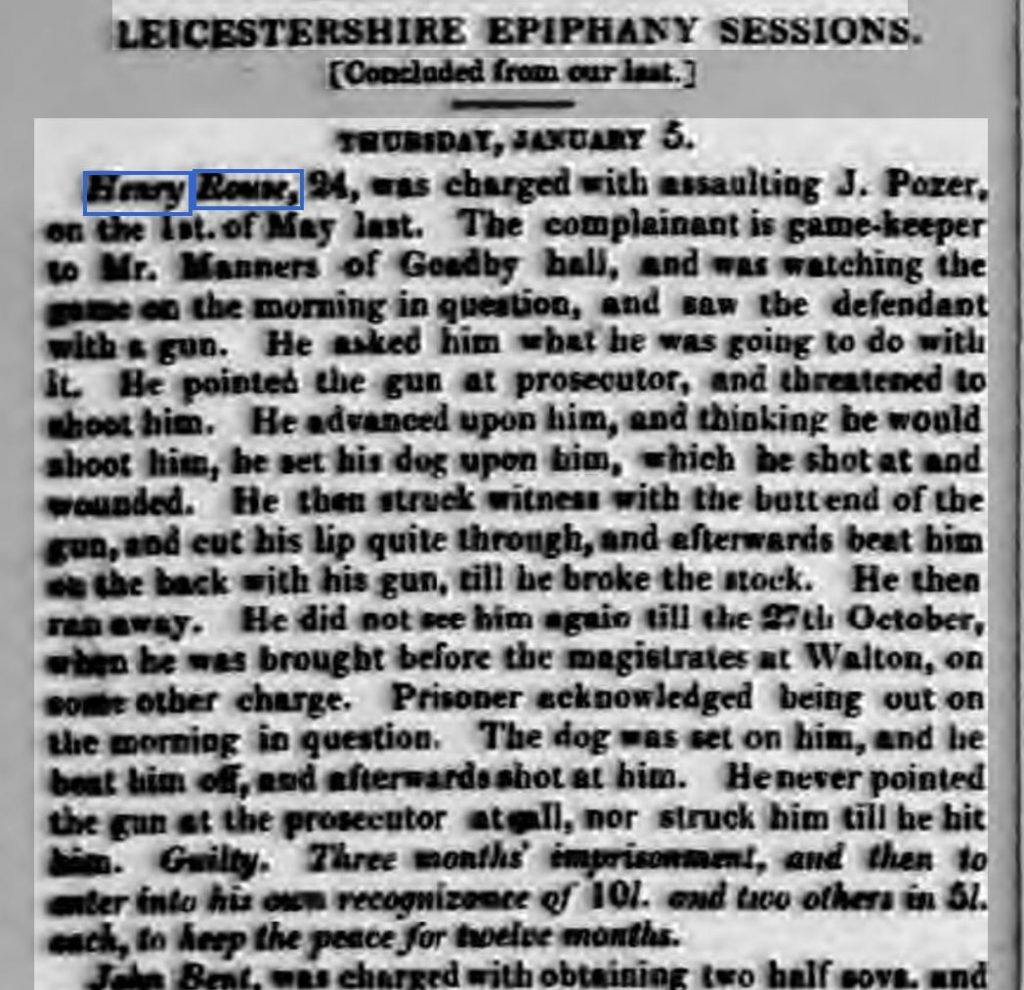

- 13th January 1843: Leicester Journal – jailed for assault of a gamekeeper.

- “Thursday January 5th. Henry Rouse, 24, was charged with assaulting J.Pozer, on the 1st May last. The complainant is gamekeeper to Mr Manners of Goadby Hall, and was watching the game on the morning in question, and saw the defendant with a gun. He asked him what he was going to do with it. He pointed the gun at prosecutor, and threatened to shoot him. He advanced upon him and thinking he would shoot him, he set his dog upon him, which he shot at and wounded. He then struck witness with the butt end of the gun, and cut his lip quite through, and afterwards beat him on the back with his gun, till he broke the stock. He then ran away. He did not see him again till the 27th October, when he was brought before the magistrates at Walton, on some other charge. Prisoner acknowledged being out on the morning in question. The dog was set on him, and he beat him off, and afterwards shot at him. He never pointed the gun at the prosecutor at all, nor struck him till he hit hi. Guilty. Three months imprisonment, and then to enter into his own recognizance of 10/- and two others in 5l. each, to keep the peace for twelve months.”

- Note: connection to Walton where his brother, James and sister, Ann are later found.

- Note: ‘other charges’; it seems that Henry Rouse wasn’t convicted as often as he offended …

- 6th January 1844: Leicester Chronicle

- Samuel Morrison is charged with stealing a saddle and acquitted; Henry Rouse speaks in Morrison’s defence – he is described as ‘son of a neighbouring farmer’. The prosecution question Rouse’s character but ‘the only thing against him was that he had once assaulted a gamekeeper’.

- 3rd January 1845: Nottingham Review – Henry Rouse reported as the victim of the theft of an accordion by John Green.

- The theft takes place in Nottingham; one of his accomplices is Samuel Morrison who is a carrier between Hose, Bingham and Nottingham.

- It is also possible that his sister Ann is resident in Nottingham at this time; there is no trace of her in the census of 1841 but she is living in Nottingham in 1851 (census) and 1853 (news report).

- 21st March 1845: Nottingham Review – very long front page 4 column report on John Green (baker and grocer and, it seems, receiver of stolen goods) including the theft of an accordion from Henry Rouse of Hose.

- Fascinating snapshot of the time

- The theft was from the Market Place – likely to be Nottingham; “Henry Rouse of Hose, Leicestershire, identified the accordion as his property. It was stolen from a basket in the Market-place, on the 17th of December.”

- John Green is apparently very respectable and many neighbours stand as character witnesses; however, he is found guilty (the jury do no more than ‘turn around’ before deciding) and deported for seven years. ‘The prisoner was borne from the dock fainting.’

- 2nd May 1845: Nottingham review – Discovery of Burglars:

- A vivid account of the discovery and arrest of Henry Rouse and his associates.

- They are described as having terrorised the neighbourhood for some time.

- At the burglary of the draper’s shop in Bingham, a distinctive knife was found; two policeman set about tracking down its owner. It is found to have belonged to ‘Henry Rouse, formerly of Hose, but then a soldier at Leicester’.

- Rouse is tricked into claiming the knife as his own and, it is reported, believing his associates to have ‘split’ on him made full confession, named Samuel Morrison (carrier from Hose and Bingham to Nottingham) and Richard Sarston, labourer of Hose. The stolen goods are recovered from their hiding places in Samuel Morrison’s home.

- They were examined by magistrates in Melton Mowbray, moved to Bingham and then (‘on Thursday’) committed to the County Gaol at Nottingham for the next assizes.

- The final paragraph details Samuel Morrison’s role; he was considered respectable but it was now apparent that his work as a carrier allowed him to convey large quantities of stolen fowl to market (‘the farmers have missed poultry, generally on the mornings he had to go to Nottingham’).

- 3rd May 1845: Leicester Chronicle:

- ‘Capture of the Hose and Melton Burglars. For some time past, a number of extensive burglaries have been committed in the neighbourhood of Bingham, Hose and Melton Mowbray; and the police of both Counties have been on the alert for the discovery of the offenders. At length they have succeeded; and the following may be relied upon as the ‘reality’ divested of the ‘romance’ which has been palmed upon some of our London contemporaries …’

- This account records that the knife belonged to ‘Sarson’ and that it was Sarson/Searson who made terms to save himself. Also that the stolen goods were found in both Rouse’s and Morrison’s sister’s houses.

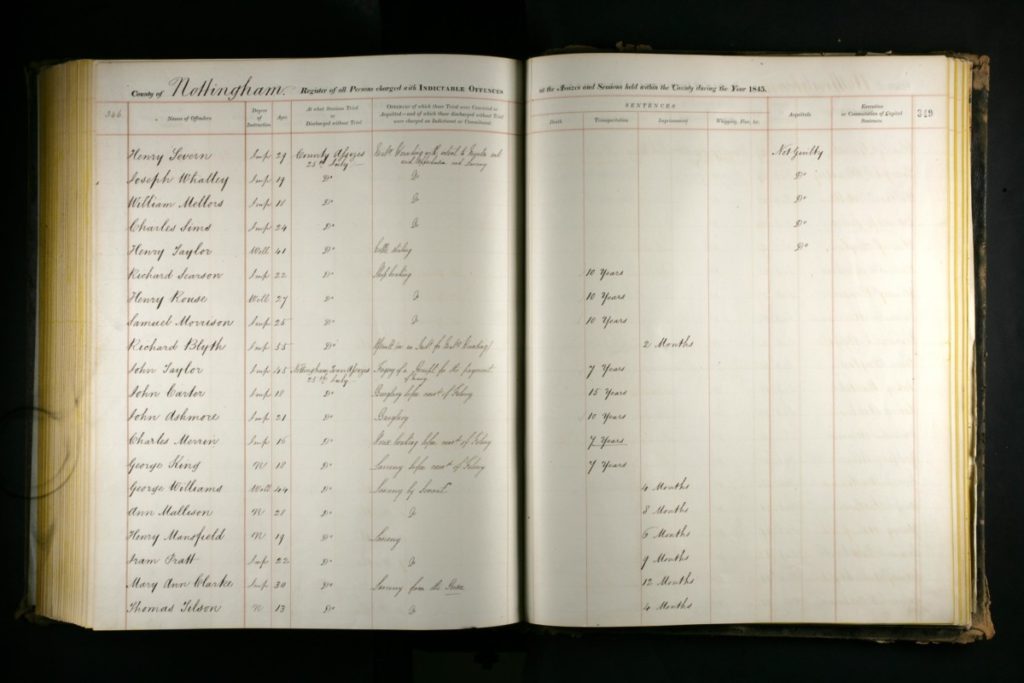

- 25th July 1845, Nottingham Review reports:

- “Richard Searson, labourer, Hose, Henry Rouse, cooper, Hose, and Samuel Morrison, labourer, Hose, burglariously entering the dwelling house of John Bailey, at the parish of Bingham, on the night of the ninth of March last, and stealing two yards of kerseymere, two waistcoat pieces and other articles.”

- His occupation as a cooper is also recorded in New Zealand.

- 1st August 1845: Nottingham Review reports on the conviction and deportation of Henry Rouse and Samuel Morrison:

- The burglary (with pistols) of a draper’s shop in Bingham, Notts, 9th March 1845.

- “This case excited great interest as the prisoners have long been the terror of the neighbourhood of Bingham, Melton Mowbray and the villages in that part of Leicestershire.”

- Richard Searson, one of the prisoners, pleaded guilty and gave evidence against his associates. Searson had been a labourer employed by Rouse. Searson was arrested on the [11th/14th] April. The defence imply that Searson was ‘simple’ and that he had been coached in what to say.

- In cross-examination, Searson said that ‘he supposed that great goose, Rouse, had been telling’.

- The jury only took a few minutes to find all three guilty and they were all sentenced to deportation and ten years.

- 15th August 1845: Henry Rouse, Samuel Morrison and Richard Searson are removed to Milbank Prison ahead of deportation.

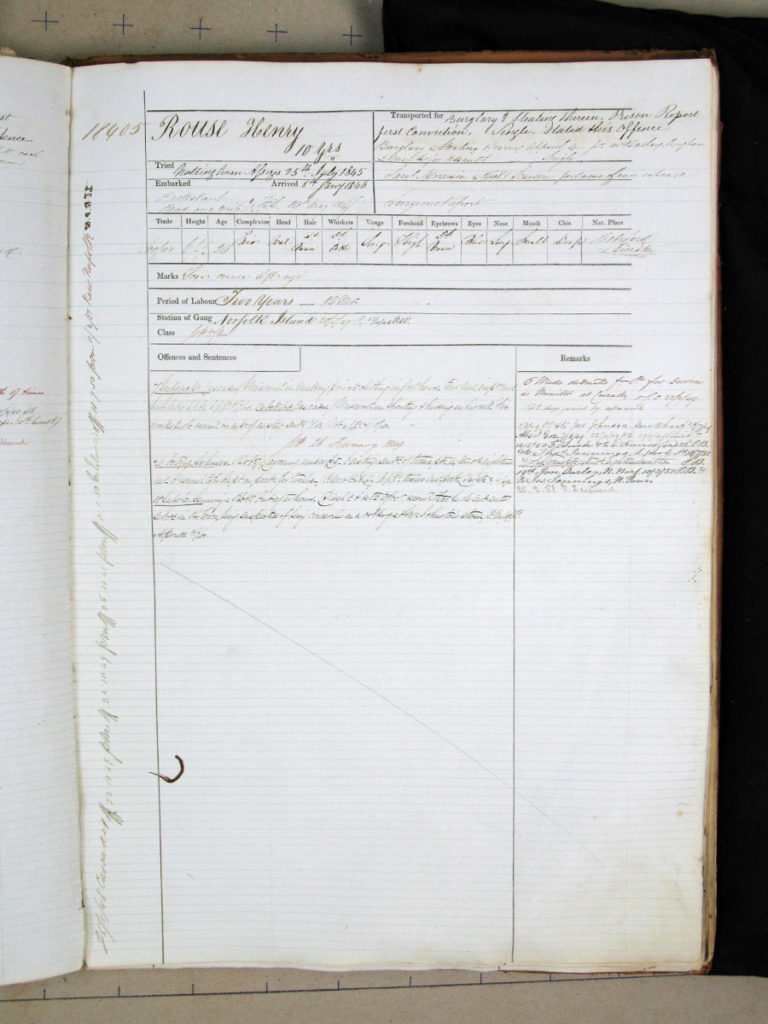

- 1845: Millbank Prison record:

- Henry Rouse – age 27 – single – reads & writes well – cooper – 25th July 1845 Nottingham Assizes – burglary – ten years deportation – transferred from Nottingham County Gaol 7th August 1845 – Previously imprisoned for an assault, is supposed to have committed much depredation for about four years and was a dread to the neighbourhood – 19th August 1845 for ‘Mayda’ for Norfolk Island.

- Samuel Morrison (as Rouse except) age 25 – read & write imp – labourer – once tried on a charge of felony and acquitted; is supposed to have committed much crime.

- Richard Searson – (as Rouse except) age 24 – married 2 children (his convict record states 3 children) – read imp – First time, supposed to have been much influenced by Rouse and principally under his control he pleaded guilty, made a full statement of the robbery and his evidence was received by the Court at the time of the trial.

- 29th August 1845: Henry Rouse departs from Woolwich on The Mayda (place of origin, Bottesford, Leics)

Timeline: 1846-1855 (Australia and England)

(records of most of Henry Rouse’s activities are dependent on news reports which vary in quality, particularly those written after his death)

- 1846 to March 1853: (Convict records; very faded and largely illegible)

- Arrival date 8th January 1846.

- Record no. 18405; tried Nottingham Assizes 25th July 1845

- Protestant/Can read and write/Trade – Cooper

- Transported for burglary and stealing therein. Prison Report first conviction, Single, stated this offence burglary and stealing wearing apparel […] from Mr Bailey Bingham

- [… …] for assault. Single. (assault refers to previous conviction in 1843)

- Samuel Morrison & Richard Searson for same offence [on house]

- [Surgeon … post]

- Height 6ft – age 30 – complexion fair – head oval – hair light brown – whiskers [light brown] ditto – visage long – forehead high – eyebrows dark brown – eyes blue – nose long – mouth small – chin [deep] – native place Bottesford Leicester.

- Marks – scar corner left eye

- Period of Labour Two Years _ 12 mths

- Station of Gang; Norfolk Island 20/5/47 13/11/48. Class […]

- January 1848 – February 1851: (Convict records) – regular notes referring to am or pm ‘off’ [work]. New Norfolk/Norfolk Island

- Remarks (largely illegible):

- 6 weeks deducted […] for services

- as Monitor at [… …] 0 22/2/49

- 54½ days […] by extra work

- 1/3/49 [PB & to John] Johnson New Wharf 28/7/49

- [Abs’ed] Gaz. 7/8/49 22/10/49 PB 21/11/49 […]

- 14/5/50 [G Buck … … Hanesford] 22nd PB

- [ditto] Thomas Jennings, [L. … …] 18/7/50

- 26/10/49 [hours …] extended [eighteen months] P.B.

- 19th Jon. Darley, [North Norfolk] 10/3/51 P.B. [&]

- to [Thomas] Jennings, [Norfolk Town]

- 25.2.51 [M. L….]

- Offences and Sentences (largely illegible):

- 7th July ’48 [pm] [… … miscon… in] making private clothing in Gov’t hours [… misconcept] and hard labour [… … …] 8/7/48.

- 14th [Sept] ’48 […] [miscreant] in shouting & hiding in his cell [six] weeks [… …? …] [14/8/5] of [rest illegible]

- 21/10/48 [ditto? shouting & hiding in cell?]

- [initials] 26th February 1849

- [26/…/49] […]. […] larceny […] £5 [… …] of [transported] [… eighteen] [… …] [to be kept on book for twelve] [… Feb … … twelve … … …] 2/11/49

- 18 July ’50 [… … …] after hours [… … … Gov’t record] that he do not enter service in […] being suspected of [being] concerned in a robbery at Mr Johnson’s stores.

- (KA) Sources report that 18 months were added to his sentence because of a theft.

- Conditions on Norfolk Island were extremely brutal and following investigation the penal colony was closed down. Prisoners were moved to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania).

- 1st March 1849: (Convict records) – in the employment of John Johnson, New Wharf for 6months – rate of wages £10.0.0.

- (1851; a number of reports of Henry Rouse, Bilsthorpe (which is in North Nottinghamshire) in relation to poaching – very unlikely to be the same Henry Rouse; convict records include notes from these dates)

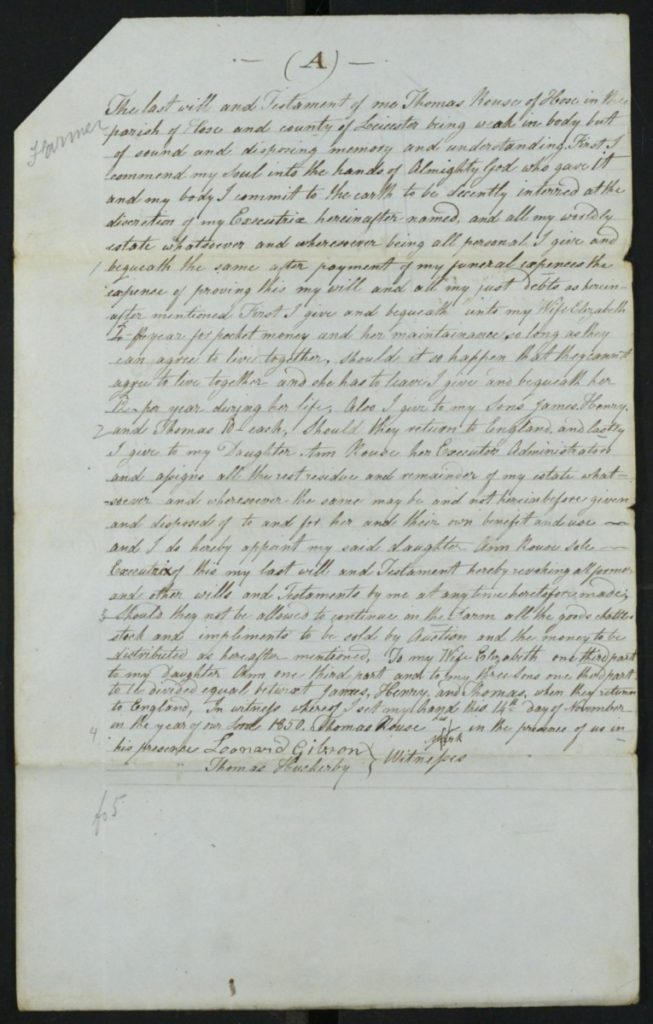

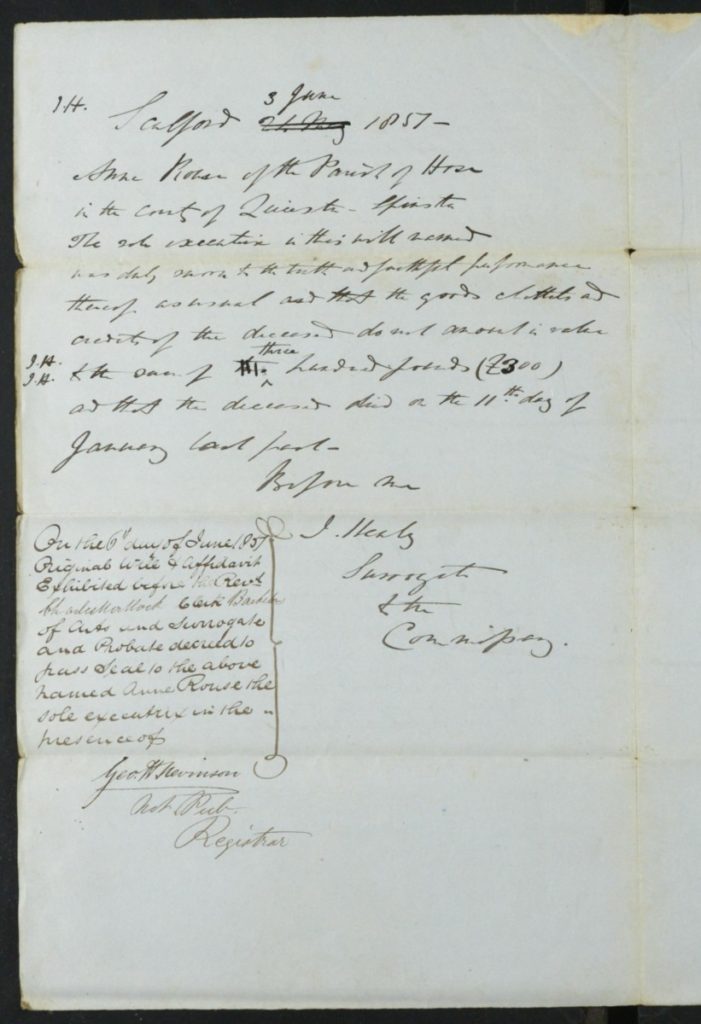

- 1851: Henry Rouse’s father dies. His sister Ann is the sole executrix; bequests are made to Henry if ‘he returns to England’ (see lineage).

- 1852: (KA) “When gold was discovered in Australia he absconded despite being denied a ticket of leave, and by 1852 he was in Ballarat under the new name of Henry Beresford Garrett.”

- 1852/3: If his sister’s report (below) is correct then Henry (Rouse) Garrett appears to have made a return journey to England sometime in 1852/3.

- During his Court Hearing in London 1855 he is said to have made the journey to England to escape and also to sell gold (which appears to have been reasonably easy to do).

- Perhaps he made a similar journey at this time.

- (potential/unverified) Victoria Inward Passenger List – Henry Garrett age 29, clerk – arr. October 1852, Port Phillip – Ship Hibernia – depart Liverpool. It seems unlikely to be the same Henry Rouse, although it could fit with this return journey to England)

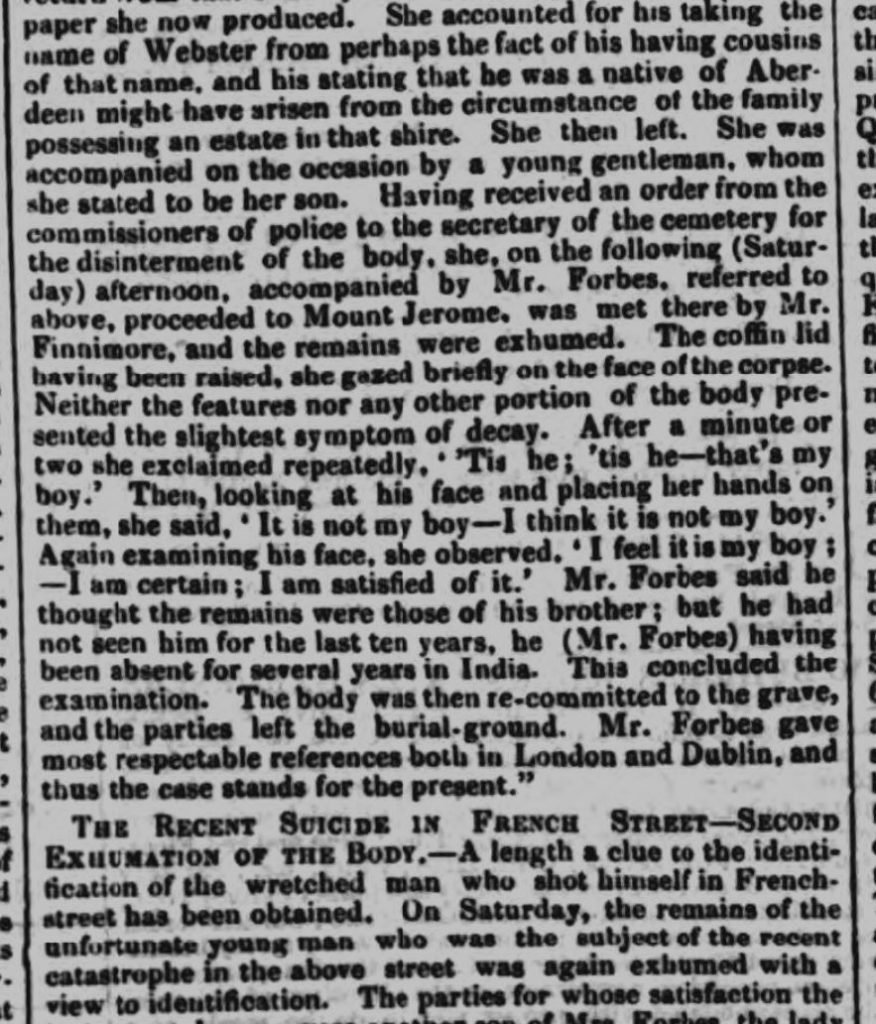

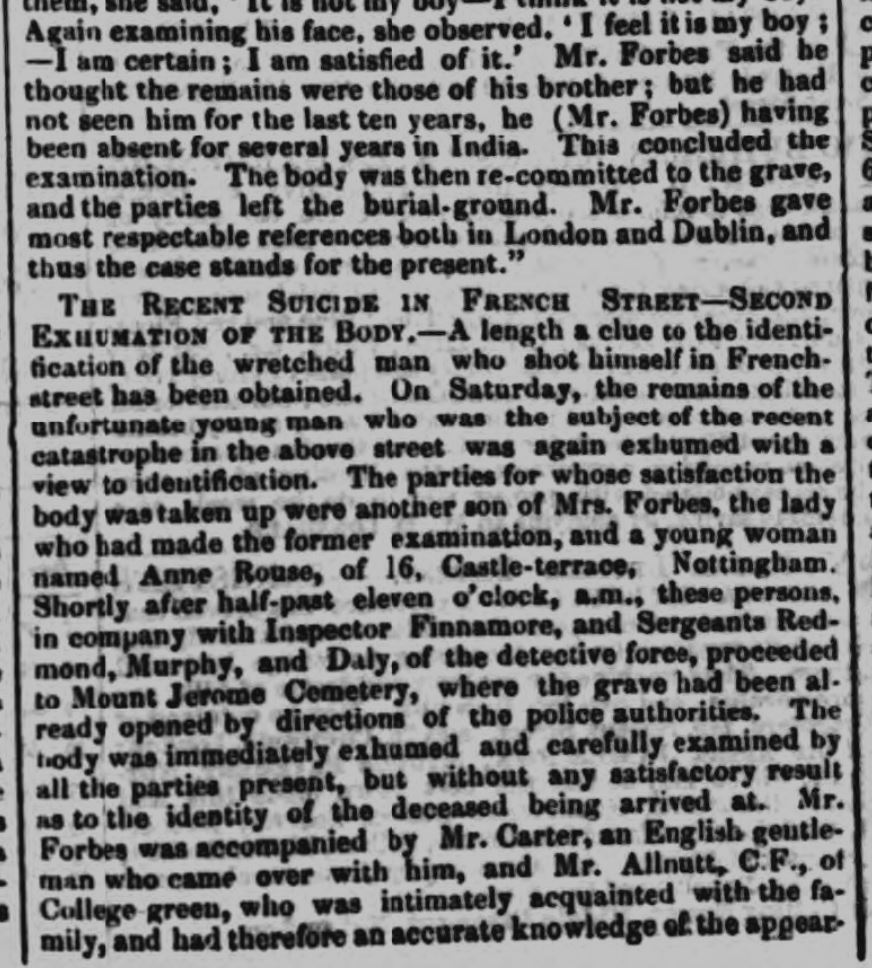

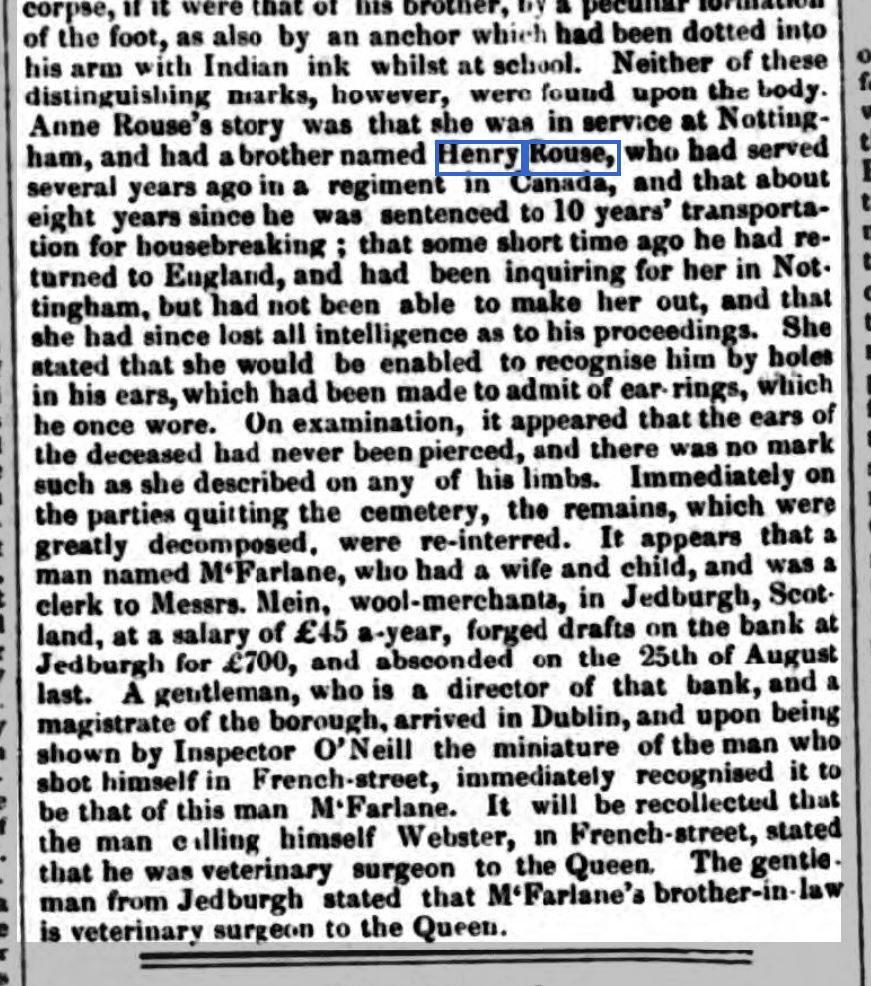

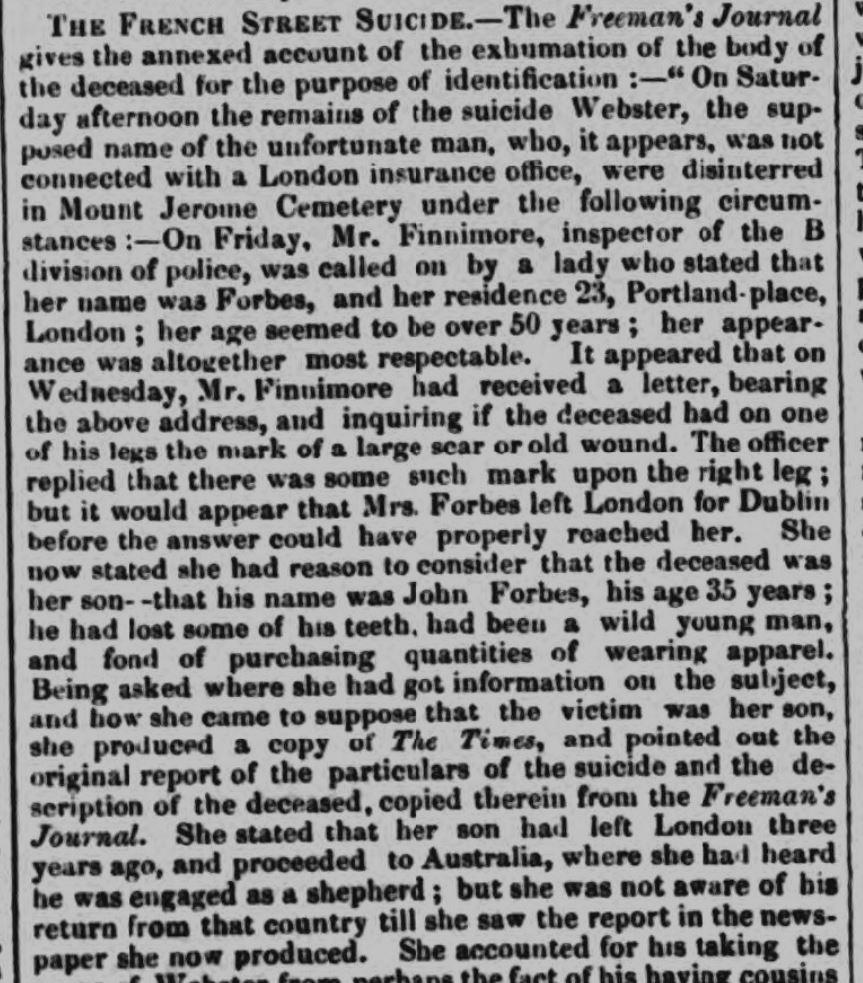

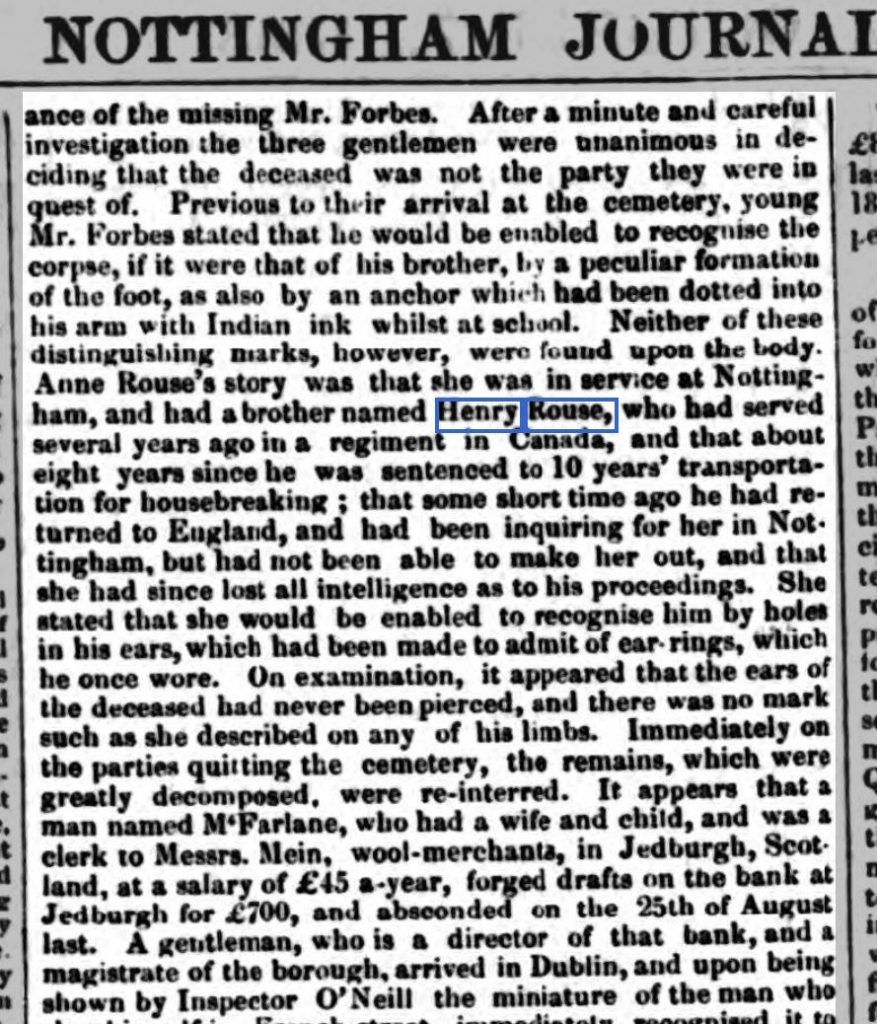

- 7th October 1853: The Nottingham Journal reports on attempts to identify the body of ‘The French Street Suicide’:

- Ann Rouse (sister of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) requests to see the exhumed body seemingly concerned that it is her brother, Henry – it isn’t him.

- It is reported that she was in service in Nottingham and that her brother had recently returned to England and he had been enquiring (unsuccessfully) after her in Nottingham; she had then ‘lost all intelligence as to his proceedings’.

- She told them that he had served several years ago in a regiment in Canada and that he had been deported about 8 years previously for housebreaking.

- She gave identifying marks; ‘holes in his ears, which had been made to admit of ear-rings, which he once wore.’ There is reference to other marks but they are not described.

- It is known that Rouse returned to England following the Melbourne bank robbery in 1855 but this incident points to him having been in England in 1853 (before his ten year sentence is completed).

- 1854: (potential/unverified) Victoria Outward Passenger List: HB [Henry Beresford?] Garrett – age 43 – born 1811 – depart Victoria October 1854 – destination Sydney & Twofold Bay – ship name Waratah – ship’s master William Bell.) – doesn’t tally with news reports, below.

- 1850s: ‘The mysterious Australian bushranger who terrorised New Zealand’ (Tony Wright 2019); an article discussing Henry (Rouse) Garrett’s activities under the unlikely alias ‘Codrington Revington’ when he is said to be a bushranger in the Port Fairy area outside Melbourne, holding up mail coaches;

- “Portland historian Bernard Wallace quotes the History of Postal Services in Victoria concerning the hold-up of June 29, 1850: “The bushranger Codrington Revingston plucked the mailman from his horse and after kicking him a few times, rode away with the horse and bags.” He was captured, drunk, but escaped from the ship that was to take him from Warrnambool for trial in Melbourne. Though handcuffed, he jumped overboard and swam for it, his police guard failing in their efforts to shoot him. He was back holding up a mail coach on the road to Portland a few days later.”

- The article goes on to suggest a further alias of ‘William Green’ and also tells how the area he ‘haunted’ became known as Codrington’s Forest and was later named officially ‘Codrington’. When a £30 reward is offered by the Governor of Victoria (La Trobe) for his capture, the bushranger puts an advert in the Belfast (later Port Fairy) Gazette, “£100 to any man or old woman who will deliver into my hands Charles Joseph La Trobe, and my word if I get hold of him I’ll work the shine out of his carcass!”.

- Whilst legend and physical descriptions tally with Codrington Revington being an alias of Henry (Rouse) Garrett these activities seem to crossover with prison records on Norfolk Island (further research needed).

- December 14th 1854: Melbourne bank robbery

- Maoriland Memories (1906): First New Zealand Bushranger; lengthy article outlining full details of the Melbourne bank robbery including the men involved and a step-by-step account and including extracts from contemporary news reports:

- This account certainly paints Henry (Rouse) Garrett as the ringleader; he is in Ballarat living in a tent amongst the gold-diggers.

- The revolvers are said to have been unloaded and paper used to make them look loaded

- Garrett was one of the two men who entered the bank, the other two standing watch outside

- £14,300 was taken in ‘notes, gold and silver and 350 ounces of unminted gold’

- The four men split up after the robbery and Garrett ‘disposed of his tools and tent and took cobb’s coach to Melbourne and almost immediately sailed for London’.

- Boulton, one of the thieves, appears to have tried to exchange some of the stolen notes in the same bank on the following day, the police were called and all three men were arrested quickly afterwards.

- The article includes a copy of an article from the Illustrated London News February 17th 1855; this report says the thieves got away with £34,000 (£17,000 in notes and several bags of gold worth £17,000) and ‘the probable flight of the thieves to England’. The Colonial Government offered a reward of £1,600.

- It also reports, that the robbery was committed by ‘four of those out and out villains who committed several fearful atrocities at the diggings.’

- A Melbourne detective named Webb followed Henry (Rouse) Garrett to London and tracked him down fashionably dressed and in fashionable lodgings near Oxford Street. After watching him for a few days he made the arrest. £2,000 was recovered.

- Melbourne Argus 2nd August 1855: reports that Garrett had arrived back in Melbourne on the previous day having travelled, in custody, on the ship Waratah from Sydney. The report says that Garrett had left from Liverpool (April 21st) on the ship Exodus in the charge of Captain Hampton and four other police officers arriving in Sydney on the 26th July. Also on the ship were 100 English police officers on their way to Sydney for police duty.

- “His custodians describe his conduct as evincing those traits of ruffianism which a long and complete acquaintance with crime, as taught in the penal schools at Port Arthur would be sure to inculcate.”

- He was sentenced to 10 years ‘hard labour on the roads or other public works of the colony’

- The article goes on to describe the workings of the Otago gold fields, the price and quality of gold and the security arrangements before introducing Henry (Rouse) Garrett as the first bushranger to work the area.

- August 1861: having served 6 of his 10 years Henry Beresford (Rouse) Garrett was released from Pentridge Prison on a ticket of leave.

- Early 1862: Garrett ‘made his appearance as the first bushranger on record in New Zealand’. The article reports that he was arrested for capturing ’23 persons near Gabriel’s Gully’ was captured and imprisoned for 8 years – this is an exaggerated account of the Woodside hold-ups, below.

- “After serving under six years of the term, Garrett – who also went under the alias of Rouse – was liberated and sent back by the New Zealand Government to Melbourne where he was promptly arrested under the Influx of Criminals Act. He complained bitterly of not being allowed to settle anywhere, and threatened to commit a murder in order that his life might be taken for him. The police authorities returned him as an ‘undesirable immigrant’ to New Zealand, but what became of him afterwards, I know not.”

- 16th June 1899: Otago Daily Times – letter containing corrections: “Another error in the same issue was the capture of Garrett in England, which was solely due to the detective on the trail making friends with a woman that Garrett’s mate in the bank robbery had picked up. I am, etc, J. Forsyth. Manor Terrace, June 14th.”

- Maoriland Memories (1906): First New Zealand Bushranger; lengthy article outlining full details of the Melbourne bank robbery including the men involved and a step-by-step account and including extracts from contemporary news reports:

- 5th April 1855: Nottinghamshire Guardian reports on the bank robbery in Australia:

- Henry Beresford Garrett is charged in London with robbing the bank of Victoria in Australia (£20,000 notes, gold and gold dust carried away in tied-up handkerchiefs) – Mr Clarkson requests Garrett should be returned to Australia to face trial.

- Their faces were covered with crape and they carried pistols (although Quin asserts these were only loaded with paper).

- Four men were involved in the bank robbery: Henry Garrett, Thomas Quin, Bolton and Marryatt. They separated immediately after the robbery with Garrett returning to England.

- Quin turned Queen’s evidence and a reward of £1600 offered.

- November 1854 he travelled from Melbourne to Sydney on the City of Sydney steamer and then to London on the ship, Dawstone (five passengers, including Garrett and his wife).

- He is accompanied by a woman who ‘it is intimated’ was not his wife when they left Melbourne but whom he married in Sydney; Mary Capey, late of London.

- The couple disembarked at Deal in Kent on March 12th 1855; the vessel arrived at London Docks on March 15th and Garrett collected their luggage the following day.

- On the 14th March they took lodgings in King street, Soho saying they had just arrived from Australia. The prisoner was carrying ‘a portfolio’ this is later described as containing a cheque for the sale of gold dust, receipts for the passage from Australia (£135.10s) and personal papers.

- Details are given of transactions to sell 499.5oz of gold dust that Garrett claimed he had dug out himself in Ballarat – a cheque for £1,967 is eventually issued to Garrett.

- A Gaol Infirmary Warden confirms Garrett as Henry Rouse (Birmingham Gaol, should be Bingham?) details of his conviction and deportation are given. Evidence from Australia is also provided by the Home Office. Questions are raised over what has happened to the rest of the proceeds from the robbery.

- Garrett was committed to Newgate prisoner pending a warrant from the House Office for his return to Australia to stand trial.

- It is reported that he said nothing during the Hearing but that on seeing the Warden from Birmingham (Bingham?), he rushed at him but was prevented from doing harm by another gaoler.

- Mary Capey: this is the only reference found for this lady – more is needed to trace her and to verify the marriage.

- ‘Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett’ by David Green; “Henry Rouse is not known to have married, although he refers to his ‘wife’ in his writings. This may have been Mary Ann Solomon of London, who is said to have given birth to his child in August 1855.”

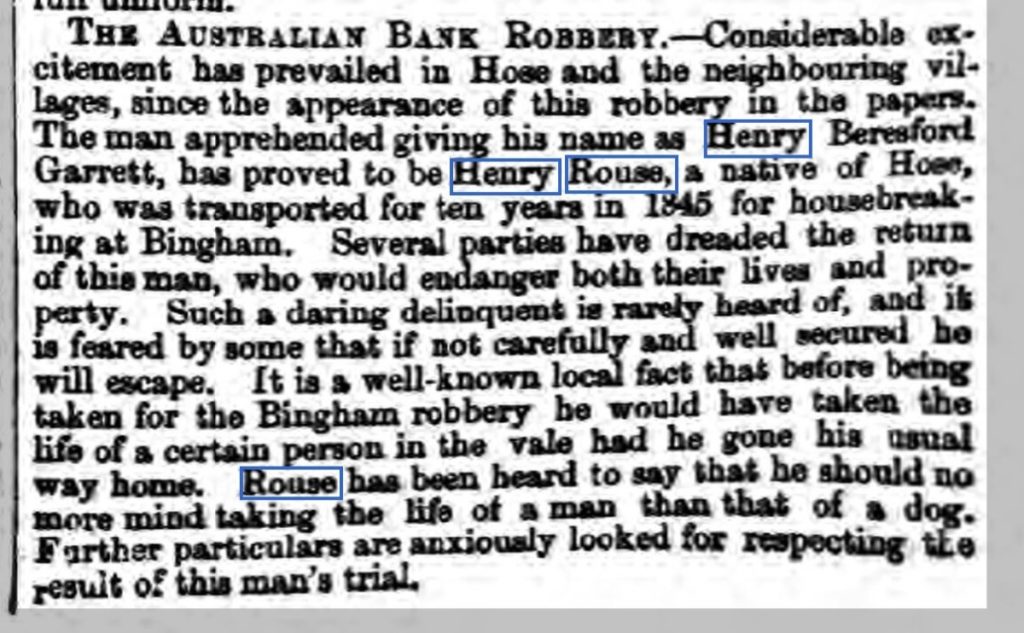

- 19th April 1855: Nottinghamshire Guardian reports on the fear in Hose following Henry Rouse’s return to England:

- “The Australian Bank Robbery. Considerable excitement has prevailed in Hose and the neighbouring villages, since the appearance of this robbery in the papers. The man apprehended giving his name as Henry Beresford Garrett, has proved to be Henry Rouse, a native of Hose, who was transported for ten years in 1845 for housebreaking at Bingham. Several parties have dreaded the return of this man, who would endanger both their lives and property. Such a daring delinquent is rarely heard of, and it is feared by some that if not carefully and well secured he will escape. It is a well known local fact that before being taken for the Bingham robbery he would have take the life of a certain person in the vale had he gone his usual way home. Rouse has been heard to say that he should no more mind taking the life of a man than that of a dog. Further particulars are anxiously looked for respecting the result of this man’s trial.

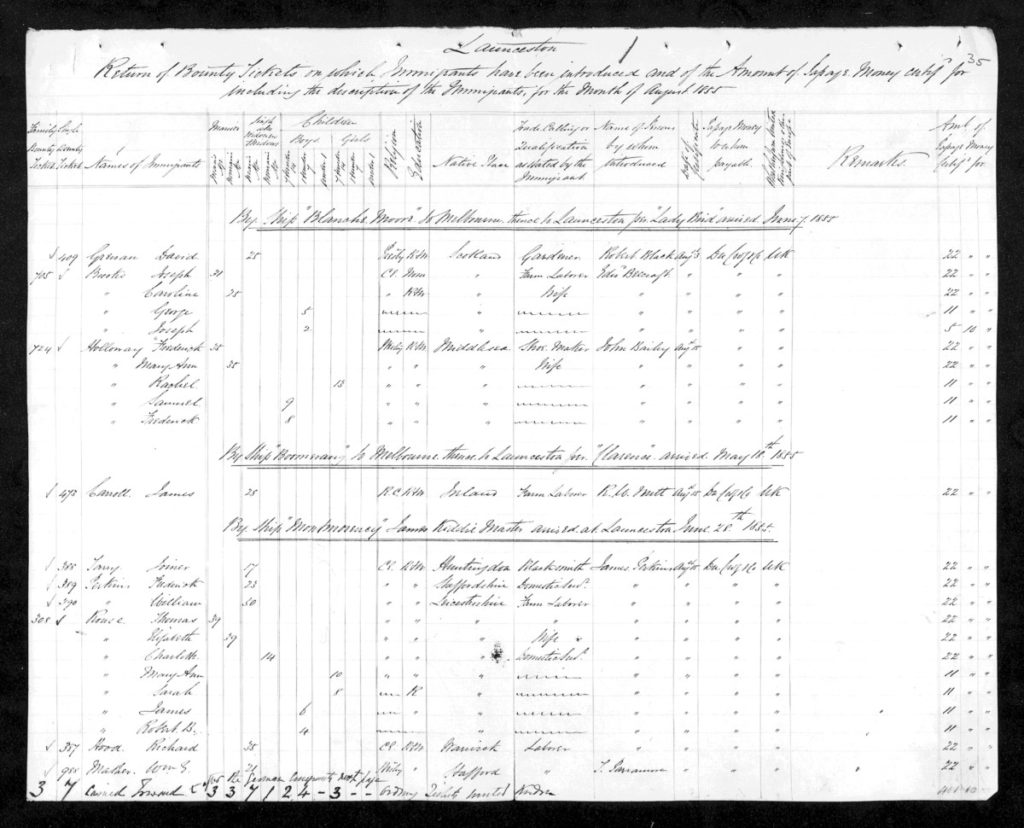

- 1855: Thomas Rouse (brother of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) and his family emigrate on the Ship Montmorency to Launceston, Tasmania, Australia arriving 28th June 1855 (as assisted migrants). No trace has been found of the brothers having any contact with each other in Australia.

- 15th November 1855: Nottinghamshire Guardian publishes a letter from ‘A Visitor at Hose’ written to correct errors in reporting of Rouse’s activities. The letter is quite highly charged and speculative but it states:

- The letter follows news of Garrett’s arrest in London for the bank robbery in Australia and makes the point that Rouse and Garrett are the same man.

- Rouse adopted the name Garrett after ‘a very respectable inhabitant’ of Hose. When reproached Rouse/Garrett is said to have replied that he hoped he hadn’t disgraced the name.

- The letter doubts a report from Melbourne (Australia) that whilst in London, Rouse/Garrett had been a nobleman’s valet and was using the name, D’Orsay. He also doubts reports that Rouse had been a ‘plunderer of railroads’.

- The writer says that Rouse had been absent from Hose for many years having gone to sea and becoming a pirate when he was responsible for burglaries and murders (he is said to have boasted of these deeds).

- The writer says that Rouse had only just returned to Hose when he was taken for the burglary in Bingham (note; this burglary took place in 1845 and Rouse can be placed in Hose in the 1841 census).

Timeline: 1856-1885 (Australia and New Zealand)

(records of most of Henry Rouse’s activities are dependent on news reports which vary in quality, particularly those written after his death)

- 1855/6: On his return to Melbourne, Australia Rouse is sentenced to ten years on the prison hulks in Hobson’s Bay. Once again, conditions are brutal:

- (KA) “By his own account Garrett witnessed the murder of the cruel warden John Price, who was beaten to death by a mob of prisoners in a dispute over inedible bread. He made much of the idea that a little kindness – just a little bit of good bread even at the last minute – might have saved the warden from his grisly fate. Unbearable cruelty, he declared, is how the penal system turns desperate men into monsters.”

- Otago Witness 22nd January 1881: “Finding the Victorian field of enterprise worked out, Garrett sailed for New Zealand, where after a short stay, he next turned up in Sydney, but soon agin the police Nemesis was on is trail and we next hear of him as being an inmate of the establishment of his fellow voyager in the Exodus, for trial, for being concerned in the mid-day sticking up of the Paramatta street branch of the Bank of New South Wales; but, although his accomplices were convicted, he escaped again, however, to be 2wanted2 by the police in New Zealand and accordingly he was forwarded across the sea to answer for crimes committed during his short stay in that colony – resulting in another period of penal hard labour.

- 1861: (KA) “When gold was discovered in Otago in 1861 Garrett had finally managed to obtain the coveted ticket of leave. He immediately took ship for Dunedin, robbed a gun shop, and joined up with three mates for the daring heist. A fortnight later he was back on his way to Australia. He enjoyed only three months of freedom before being nabbed in Sydney and sent back to Dunedin to face trial. Despite his impassioned performance he was sentenced to eight years in Dunedin Gaol.”

- 1861: Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett by David Green;

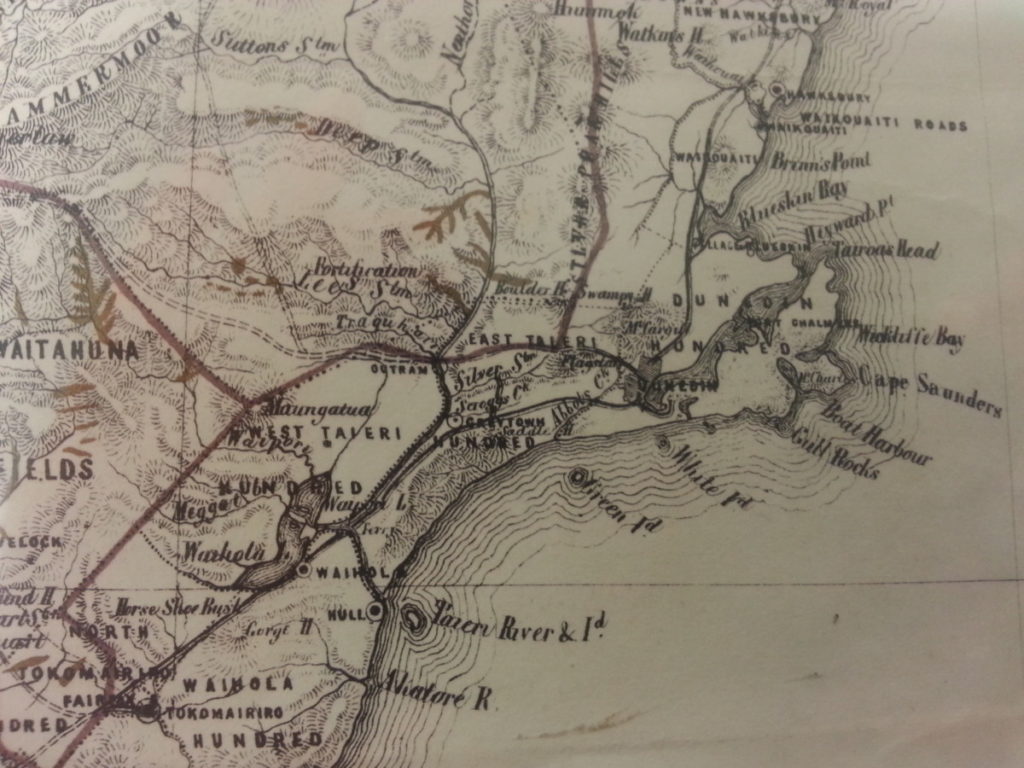

- “In 1861 Garrett was granted a ticket of leave, and on 7 October arrived in Dunedin on the Kembla en route for the Otago goldfields. After obtaining weapons by robbing a gunsmith, he and several companions carried out a ‘most daring Highway Robbery under Arms’ at the foot of the Maungatua range, on the track between Gabriels Gully and Dunedin. The ‘Garrett gang’ had overheard diggers boasting about the amount of gold they were carrying, and were thus able to choose whom to waylay. Fifteen men were tied to trees, parted from gold and property worth some £400, and then treated to light refreshments. There was panic in Dunedin when the victims eventually freed themselves and raised the alarm. Otago police initially detained only a few innocent diggers and a new member of their own force, but the gang’s lookout was eventually caught. Henry Garrett was arrested in Sydney in December, and sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment in Dunedin in May 1862.”

- 18th October 1861: Maungatua/Woodside robberies

- (KA) Woodside Glen and New Zealand’s Gentleman Highwayman.

- Woodside and Woodside Glen was on the road between the goldfields in the Maungatua Mountains and Dunedin; during the goldrush years this route would have been relatively busy.

- Maunga-atua; “The Maori have two legends about the origin of this rock. One involves the legendary canoe Takitimu of the Southland people, which was hit by the great wave Maunga-atua (now the Maungatua range). A man named Aonui was lost overboard, and he remains here as this rock today. The canoe itself has become the Takitimu Range in Southland.”

- The first victim was gold-seeker Charles Corstophon heading up towards the diggings; 4 men armed with pistols dragged him into the gully, robbed him of his valuables and then bound him hand and foot.

- During the course of the day a further 14 men suffered the same fate.

- Legend has it that Henry (Rouse) Garrett (described in reports as the tallest of the highwaymen) gave the victims blankets to lie on, tea, whisky and re-filled their pipes for them. When night fell they were tied to separate tress and left – Rouse covered them with blankets and tents for warmth.

- Corstophon and another victim named William Maloney managed to free themselves and then released the others – some had been tied up for 14 hours.

- The freed prisoners hurried down the hill to Woodside and the nearest Magistrate – some £400 had been stolen from them.

- This was the beginning of the legend of the Gentleman Highwayman and the first reference to Henry (Rouse) Garrett in New Zealand.

- 1862: ‘Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett’ by David Green;

- “After an unsuccessful attempt to break out of Dunedin gaol with Richard Burgess in September 1862, Garrett seems to have taken no further part in prison disturbances. He became involved with the Plymouth Brethren, probably in hopes of an early release.”

- Waikato Times (1885):

- ‘Early in 1862, Garrett, Burns, alias Anderson, and a number of them committed a series of robberies at Maungatua, taking possession of a particular point, one day from sunrise to sunset and sticking up travellers who passed. Among these travellers was the late lamented Father Moreau, who was then returning from a mission on the Tuapeka goldfields. Garrett and one of his companions insisted on bailing him up, while the other desperadoes some of whom knew the reverend gentleman, objected, and he was allowed to go by unmolested. It being mentioned to him afterwards, Father Moreau remarked that the bushrangers would not have got much if they had bailed him up, as all he had in his possession at the time was a threepenny bit.’

- Maoriland Memories (1906): First New Zealand Bushranger (see 1855, above):

- After describing the events around the 1855 bank robbery, the article goes on to describe the workings of the Otago gold fields, the price and quality of gold and the security arrangements before introducing Henry (Rouse) Garrett as the first bushranger to work the area.

- August 1861: having served 6 of his 10 year sentence in Melbourne, Henry Beresford (Rouse) Garrett was released from Pentridge Prison on a ticket of leave.

- Early 1862: Garrett ‘made his appearance as the first bushranger on record in New Zealand’. The article reports that he was arrested for capturing ’23 persons near Gabriel’s Gully’ was captured and imprisoned for 8 years – this is an exaggerated account of the Woodside hold-ups.

- “After serving under six years of the term, Garrett – who also went under the alias of Rouse – was liberated and sent back by the New Zealand Government to Melbourne where he was promptly arrested under the Influx of Criminals Act. He complained bitterly of not being allowed to settle anywhere, and threatened to commit a murder in order that his life might be taken for him. The police authorities returned him as an ‘undesirable immigrant’ to New Zealand, but what became of him afterwards, I know not.”

- Woodside Glen and New Zealand’s Gentleman Highwayman (Amanda@KiwiAdventures)

- (KA) “As I slipped and scrambled and jumped from one boulder to the next, I reflected on the enigmatic character of Henry Garrett. He was described as unusually tall, with blue eyes and brown hair which tended to grey. There was a scar above one eyebrow and he walked with a shuffling gait, possibly the result of many years in irons. Although he had no formal education, he was keenly intelligent and taught himself to write eloquently. He scorned religion but knew his bible front-to-back as it was one of the few books provided in prison. It was a great source of stories, he said. In court he was theatrical, defending himself with threats and accusations of conspiracy. Throughout his life he carried a smouldering sense of injustice, blaming all of society for the cruelty inflicted by the harsh penal system. He was charismatic and capable, a man who could have easily succeeded as a law abiding citizen. And yet he continued to turn to crime, spending fifty years of his life in various prisons.”

- c.1862: (KA) Garrett was probably put to work levelling Bell Hill to prepare it for the construction of First Church.

- c.1868: (KA) After serving six years of his sentence he was released. The Dunedin police sent him to Australia, but he wasn’t wanted there either so they sent him right back.

- Maoriland Memories (1906): First New Zealand Bushranger (see 1855, above):

- “After serving under six years of the term, Garrett – who also went under the alias of Rouse – was liberated and sent back by the New Zealand Government to Melbourne where he was promptly arrested under the Influx of Criminals Act. He complained bitterly of not being allowed to settle anywhere, and threatened to commit a murder in order that his life might be taken for him. The police authorities returned him as an ‘undesirable immigrant’ to New Zealand, but what became of him afterwards, I know not.”

- (KA) He ended up working in his old trade of cooper at a local brewery, where by all accounts he was a good employee – a kind and generous man who was nevertheless inclined to hold grudges. This worked out well…until he was caught in a seed store after breaking in and pilfering some small items.

- (KA) It is strange how readily Garrett surrendered, almost as if he was resigned to his fate. What could have led him to throw away his new law abiding life for a few trinkets? Was he a kleptomaniac? Did he arrogantly think himself above the laws of society? Or, as some have suggested, could he simply not function outside of the prison system that had been his home for so long, and so deliberately arranged his return?

- 1868? (KA)The judge was not inclined to be sympathetic and handed down a sentence of twenty years. Garrett settled down to study and write from behind bars.

- 1866: Note the possibility of links between Garrett and the notorious Burgess & Kelly Gang responsible for 5 murders on the Maungatua Trail and executed in 1866; Richard (Hill) Burgess wrote an excoriating attack on Garrett just before his execution (see 1881 article, below – Otago Witness; Extraordinary Career of Crime); it seems they were prisoners at the same time in the 1860s. Burgess’ fellow gang leader was Thomas (Noon) Kelly.

- 1868: ‘Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett’ by David Green;

- “He was in fact released in February 1868 and sent back to Victoria by the Otago police. He was soon deported from Australia and returned to Dunedin, where he worked as a cooper in a brewery. On 9 November 1868 he was arrested while burgling a seed merchant. Inquiries revealed he had also broken into a chemist’s shop, and a search of his dwelling revealed skeleton keys, fancy confectionery, and a variety of poisons. On the assumption that he had intended to murder people who had crossed him, he received 10 years’ gaol for each burglary, to be served consecutively.”

- c. 1868: Otago Witness (22nd January 1881):

- Lengthy description of Garrett’s playing the ‘pious move’ to improve his conditions in prison in New Zealand and achieve an early release; ‘daily giving utterance to earnest exhortations to his fellow prisoners to turn from their wickedness’ and ‘weak-minded chaplains become instruments in obtaining concessions, privileges’ etc.

- The article contains a poetic account of Garrett’s peaching and the extent of his career as a burglar carrying on at the same time; ‘there had been many robberies and not a few daring burglaries but no trace of the delinquents could be found until …’ and ‘while he had worn sackcloth for his early transgressions’ and ‘in one month of his service in the church he had committed no fewer than 48 robberies’ and ‘the police found at his house the most complete set of burglar’s tools ever found in the colony.’

- 13th November 1868: Otago Daily Times – Magistrates Court. Garrett is remanded for housebreaking, being in possession of housebreaking tools and theft from a druggist (full details in the article). On the same day the North Otago Times runs a similar piece headlined, ‘Garrett Again’ and describing the crowds that gathered outside the Court.

- Garrett had been ‘elevated into a hero’

- Public opinion was against the police and courts, they were ‘hunting a man willing to be honest to death’.

- The article claims that on Garrett’s return from Melbourne, he had ‘ingratiated’ himself with a local church congregation, working as a cooper and tradesman and earning a good wage. However, the police had kept him under surveillance and his ‘hypocrisy’ had been proved when he was caught stealing from a seedsman’s premises (full detail given).

- On searching Garrett’s house a revolver, ammunition and ‘a most formidable knife’ was found.

- 19th March 1868: West Coast Times – An Ex-Convict on Reformation; the Career of a Bushranger.

- Discussion about the deficient working of the penal system, using Garrett as an example.

- ‘During 1854 Garrett’s name figured conspicuously in Victorian bushranging annals’ before robbing the bank in Ballerat in 1855.

- Following his release from Pentridge Stockade in 1861 he was ‘advised by the heads of the police department to leave the colony without loss of time or else he would be subjected to the endless persecution of the police. Acting upon this suggestion, Garrett started on foot from Melbourne on an overland trip to Sydney, with a floating capital of one shilling and a halfpenny in his pocket. After enduring many privations and surmounting numerous difficulties he arrived at his destination. Bt friendly assistance a passage was secured for him in a sailing vessel bound for a New Zealand port, and in the course of a few weeks Garrett once more felt firm earth and virgin soil beneath his tread and his individuality in a great measure screened from the prying interference of Victorian detectives.’

- Following his release after 6 years of his ten year sentence in Dunedin; ‘Shortly before his discharge and while at work in the quarries, Garrett sustained a severe injury in the knee which necessitated his going into hospital after leaving the gaol.’ Whilst in hospital the chief commissioner of police asked to know if Garrett planned to stay in Otago; Garrett said that he would because he would be persecuted in Australia but could find honest work in New Zealand; he also expressed a willingness to go to America if the Government would pay his passage. In response the police commissioner arrived at the hospital with 8 officers, arrested Garrett (and refusing him access to his doctor) and shipped him in the company of two detectives on the Steamer Auckland to Melbourne.

- Once in Melbourne, ‘he was to be charged under the Convicts Prevention Act with being a prisoner at large. When placed in front of the dock on Saturday Garrett persistently protested against being remanded. He mentioned that he had no desire to remain in Melbourne, where ‘people would set their dogs upon him’ and ‘that he preferred returning to Otago.’ He further insisted that the offence with which he was charged was a compulsory one, and had been pressed upon him by the malevolent course adopted by the New Zealand police. In fact he was guiltless of the charge. The Act provided a penalty of two years’ imprisonment for any felon landing in this colony who had not experienced the privileges of a freeman for two years previously.’

- ‘One of the detectives who accompanied Garrett from New Zealand informed the Bench that the prisoner had been arrested without a warrant.’ It seems that the authorities were in too much of a rush to ship Garrett away. Garrett challenges the system where prisoners are ‘knocked about like a shuttlecock’ between the colonies where he has ‘no right to be anywhere’. The Melbourne Argus picks up his case and the rest of the article details the issues of the status of convicts once discharged and possible solutions.

- 10th December 1868: New Zealand Evening Post

- At the sittings of the Supreme Court, Dunedin, on Thursday last, Henry Garrett, alias Henry Rouse, who pleaded guilty to two indictments, each charging him with housebreaking and robbery was brought up for sentence. In reply to the usual question, the prisoner said that he was 55 years old. The Judge – To you, Henry Garrett, I must speak in a very different tone to that in which I have addressed any other prisoner which has been brought before e me. Your career, as far back as it can be traced, has been one continuous career of crime – not alone in this colony but in other colonies, and at home as well. I feel it to be my duty to see that, for a long time to come, at all events, you have no opportunity for committing crime, or less opportunity than you have recently had. I have before me two indictments on which you have already been found guilty in this colony. You have now pleaded guilty on two indictments – knowing, of course, as you well do, what clear evidence there is against you on each – charging you with the serious crime of housebreaking and robbery. And when I consider as to one of these cases, the nature of the articles that you had stolen – the poisonous drugs which you had selected from the stock in the druggist’s shop – I cannot doubt but that for your timely arrest, you would, in all probability, ere long, have been standing in that dock arraigned for the highest crime known to the law. But, for that evil intent, you will have to answer to another and a Mightier Judge than I am. I feel it to be my my duty to pass upon you a sentence which will, in all probability, at your age, prove to be a sentence of life-long imprisonment. Therefore, with Courts of Law – or if not with Courts of Law, at all events with this Court – you will probably never again be concerned. But there is a last and Highest Tribunal before which judge and criminal – accuser and accused – must one day appear. Think of it, I beseech you; and so thinking, strive to spend the remainder of your days, in the prison to which you will be confined, in preparing for that last and most awful arraignment. If you do that, you may yet feel and prove yourself grateful for the fact that that your career of crime has been cut short by what as I have said, will most likely be a life-long imprisonment. The sentence of the Court is that upon each of the two indictments to which you have pleaded guilty, you be kept in penal servitude for ten years – those periods being cumulative. The convict was then removed.”

- 1869: Otago Witness – “To Constable John Nagle (No.510) at Dunedin, the sum of L5 has been awarded for the arrest of Henry Garrett alias Rouse, convicted on two charges of house-breaking, for which he received cumulative sentences amounting to 20 years’ servitude.”

- 1881: ‘Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Biography of Henry Beresford Garrett’ by David Green;

- “Garrett remained in Dunedin gaol until 1881, when deteriorating health brought about his transfer to Lyttelton. His daily regimen of hard labour was balanced by reading Shakespeare, the Bible, and philosophy, and by writing with idiosyncratic phonetic spelling on a wide variety of subjects, including ‘Napoleonism’, ‘Evolution’, ‘Kremation’ and ‘Womans Riets or Mision’. Some of his articles were published under the pseudonym ‘Klodopr’. Released in April 1882, by now in his 60s, he again worked as a cooper. In November 1882, however, he was caught while attempting to steal a bottle of wine from a merchant, and sentenced to the maximum possible gaol term of seven years. More hard labour followed, this time at Wellington’s Mt Cook gaol. In July 1885 he was transferred to The Terrace gaol, which had a hospital. Here he died of ‘chronic bronchitis’ on 3 September 1885.”

- Woodside Glen and New Zealand’s Gentleman Highwayman (Amanda@KiwiAdventures)

- 1881: Garrett was strong, but finally his health began to fail. And so he was moved to the kinder climate of Lyttelton in 1881.

- 1882: Then in 1882 he was released in Canterbury. He got a job as a cooper (…) nine months later he was back before a judge, having been caught in the act of stealing a bottle of wine.

- 1885: Garrett was to die in prison, passing away in 1885 at the age of 67. His funeral was attended by the governor of the jail and six fellow prisoners. Thus ended the “strange and turbulent life” of Otago’s first bush ranger.

- 1881: Otago Witness – Extraordinary Career of Crime

- The paper publishes what it calls a ‘very graphic and sensational … biography of the notorious convict Henry Garrett’; notoriety equated with Ned Kelly’s gang in Australia. At the end of the biography, the paper publishes corrections.

- Described as a ‘remarkably handsome man, of large physique, with bright, active intelligence. Nature had favoured him with more than ordinary gifts’. The article argues what a great man Garrett could have been if it hadn’t been for ‘the first unfortunate step in his life … This man of gigantic intellect, noble frame, and of untiring resolve, has become, instead of a great public figure, the hero of many bold crimes and hair-breadth escapes.’

- The article contains a different account of Garrett’s arrest in London; following the bank robbery he is said to have returned to his home country (‘having a strong amor patri’) wishing to settle down ‘to a life of honest pursuits’. However, he was spotted by London police officers and arrested as a ‘returned exile’. Meanwhile news reached London of the Melbourne bank robbery and he was returned to Australia to stand trial.

- Detail is given of the 86 police officers accompanying Garrett on his return to Australia.

- “During the service (of 10 years hard labour) it is alleged that he was in league with the prisoners implicated in the murder of the superintendent at Pentridge, Mr Price.”

- “Finding the Victorian field of enterprise worked out, Garrett sailed for New Zealand, where after a short stay, he next turned up in Sydney, but soon agin the police Nemesis was on is trail and we next hear of him as being an inmate of the establishment of his fellow voyager in the Exodus, for trial, for being concerned in the mid-day sticking up of the Paramatta street branch of the Bank of New South Wales; but, although his accomplices were convicted, he escaped again, however, to be 2wanted2 by the police in New Zealand and accordingly he was forwarded across the sea to answer for crimes committed during his short stay in that colony – resulting in another period of penal hard labour.”

- Lengthy description of Garrett’s playing the ‘pious move’ to improve his conditions in prison in New Zealand and achieve an early release; ‘daily giving utterance to earnest exhortations to his fellow prisoners to turn from their wickedness’ and ‘weak-minded chaplains become instruments in obtaining concessions, privileges’ etc.

- The article contains a poetic account of Garrett’s peaching and the extent of his career as a burglar carrying on at the same time; ‘there had been many robberies and not a few daring burglaries but no trace of the delinquents could be found until …’ and ‘while he had worn sackcloth for his early transgressions’ and ‘in one month of his service in the church he had committed no fewer than 48 robberies’ and ‘the police found at his house the most complete set of burglar’s tools ever found in the colony.’

- The final paragraph describes the writer’s relief on hearing the news that Garrett had recently been prevented from escaping from Pentonville Prison in London; ‘How he passed from New Zealand to London, the scene of his next labours, our informant is in ignorance, and he had passed from memory until the news reached us of his attempted escape from Pentonville and fortunate failure.’

- The Pentonville story is de-bunked in paragraphs of corrections published beneath this biography; this includes, ‘Garrett’s name is Rouse, and he is a native of Harby, Leicestershire, near Belvoir Castle, the baronial seat of His Grace the Duke of utland. He is one of the most dangerous class of convicts in theSouthern Hemisphere – one whom no kindness could conciliate, and no discipline tame. He graduated in the Home and Colonial prisons, where he obtained his education, which was very much neglected in Leicestershire as he much preferred the exciting life of a poacher in the well-stocked preserves of His Grace the Duke of Rutland in the beautiful valley of the Vale of Belvoir”

- There does seem to be a different Henry Rouse of Middlesex (b.1811?) actively referred to in prison and court records through these years; needs further exploration.

- The writer closes with an excoriating description of Garret written by his earlier associate/contemporary, Burgess – ‘greatest coward’ and ‘cur’ and ‘a low despicable ruffian and not one fit to rank as a first-classe professional burglar’ and ‘not one manly act did I ever see him do’.

- This is Richard Burgess of the notorious Burgess & Kelly Gang responsible for 5 murders on the Maungatua Trail and executed in 1866 (see 1866 entry, above).

- 7th September 1885: Otago Daily Times – Death of Garrett the Bushranger

- ‘The career of a man who has spent 50 Christmasses in gaol’.

- Full account of his career (includes reference to Birmingham instead of Bingham) – repeating material from elsewhere.

- “When he had the 17 tied up and their pockets emptied, like a gentle thief as he was, he made tea for them, and filled and lighted the pipes of such as smoked.”

- “He was a man who had from his secluded life read much, and yet at the same time he had mixed and conversed with men sprung from all positions and of the most curious experiences. His memory was good, and he had a vast fund of information. His name was a household word at Pentridge, where he was regarded as a high legal authority. He had studied science as well as law and was a warm disciple of Mr Darwin, being fully convinced that his principles were well proved. He was not sound in his religious views and it is stated he had no belief in God or devil. Shortly before his death, however, there were signs that this was not altogether the case.”

- “While in Dunedin and other gaols Garrett was a most turbulent prisoner. At one time he threatened the life of a gaoler and was kept in solitary confinement for three years. In Wellington, however, his conduct has been quite different, and for Mr Garvey, the Governor of the Gaol, he would do anything.”

- “Mr Garvey says he could have trusted Garrett at any time to go a message outside the prison with the certainty that he would return at the appointed hour. He was a capital, industrious workman, and while he was at Mount Cook was found exceedingly useful, doing, while in health, the work of three ordinary men. Certain work in connection with the laying of rails for the gaol tramways he did particularly well, saving a good deal of money to the department.”

- “To common thieves he had a strong objection, and would never associate with them, holding them in high contempt. Whenever any of those belonging to the humbler branches of his business went to him for advice he sent them away.”

- “On July 10 Garrett was taken ill, and Mr Garvey, seeing that he required special treatment, recommended his removal from Mount Cook to the Terrace Gaol, where there is a hospital. Mr JSM Thomson, the visiting Justice, accordingly ordered his removal and he has been there ever since. The old man has been treated kindly in his last illness and, as an instance of this, Dr Johnson only yesterday afternoon sent him a bottle of wine from his own cellar.Everything, also, that could be done by the gaoler, warders, and the other prisoners. In cold weather he has always been weak for the last 18 months, but in fine weather he has always worked. The Ven. Archdeacon Stock has been most kind and attentive to Garrett, who was grateful and attached to him, though the latter never would take part in conversation on religious subjects. Last night Garrett was evidently very ill. He was in bed, and about 7 o’clock he turned to the wall, and moaned “My God! My God!” Mr Garvey immediately sent for Archdeacon Stock, who hurried to the gaol. Though Garrett listened to the archdeacon with respect, he asked him not talk of religious matters, as it harassed him. After this he sank fast and closed his strange and turbulent life just at midnight.”

- 10th September 1885: Lake County Press – “… news of the death of Henry Garrett … died on September 2nd, aged 73, of decay of the system.”; the report includes a full record of Garrett’s life – if rather romanticised.

- It refers to his troubled domestic/home life growing up, his deportation and the later bank robbery.

- It names some of those held-up by Garrett ‘between Dunedin and Gabriel’s Gully’; a French Priest, Father Moreau and future members of parliament in Wellington – much is made of his gentlemanly behaviour and the hostages are said to have ‘made his acquaintance’ on that day.

- “He was released in 1882 by special permission, and for a short while devoted himself to literature. He contributed several biographies of gentlemen in his own way of business, in weekly parts, to a society journal in Christchurch. The name he wrote under was ‘Clodhopper’ and among the lives were those of Silas Eli, Frederick Plummer, Robert Butler and several other practitioners of eminence. They are said to have been exceedingly well sone, showing great knowledge of character and a curious and accurate acquaintance with facts. He also began a life of himself, which, unfortunately for literature, was interrupted. He was arrested in November 1882, for being found in a wholesale warehouse with about 40 or 50 skeleton keys in his possession and received a sentence of seven years from which he was released by death at 12 o’clock on the evening of the 2nd September. Garrett sometimes called himself Rouse, which the Wellington gaol authorities believe to have been his real name. Through all his career of crime it is not recorded once against him that he once shed human blood and like the highwaymen of old, he never robbed or hurt a woman.”

- 13th October 1885: Waikato Times, A Noted Convict – a lengthy report following Henry (Rouse) Garrett’s death. Additional information includes:

- That Garrett died of bronchitis

- ‘it is observed as a strange coincidence that the foreman of the jury at the inquest was one of the victims stuck up by him at Maungatua.’

- It is recorded that he ‘commenced his career of crime by breaking into a house in 1843’ although this was not really the ‘commencement’.

- After the bank robbery in 1854 ‘Garrett, with a fair companion, went to London with his portion of the spoil’.

- ‘Shortly after his release the Otago Goldfields were discovered, and in 1862 along with Burgess, Levy, Kelly and other noted criminals, he came over to Dunedin with the view of going up country to practice their profession among the diggers. It is said that Garrett professed to have another object in view – to search out one of his accomplices in the Ballarat robbery who had turned Queen’s evidence.’

- ‘Early in 1862, Garrett, Burns, alias Anderson, and a number of them committed a series of robberies at Maungatua, taking possession of a particular point, one day from sunrise to sunset and sticking up travellers who passed. Among these travellers was the late lamented Father Moreau, who was then returning from a mission on the Tuapeka goldfields. Garrett and one of his companions insisted on bailing him up, while the other desperadoes some of whom knew the reverend gentleman, objected, and he was allowed to go by unmolested. It being mentioned to him afterwards, Father Moreau remarked that the bushrangers would not have got much if they had bailed him up, as all he had in his possession at the time was a threepenny bit.’

- A different sequence of events is given for the offences leading to Garrett’s final conviction (see original article). Also, names of people in the community offering him help and employment.

- The article reports that Garrett was moved to Lyttleton in January 1881 where he was released but he quickly reoffended and was ‘lately’ transferred to Wellington; ‘A day or two before the opening of the Exhibition in Christchurch he met an old Dunedin fellow prisoner and wished to enlist him for the purpose of committing robberies.’

- ‘No murders have been laid to his charge, though it was a favourite saying of his that “dead cocks cannot crow” During the whole of his career in the Norfolk Island, Tasmania, Victorian and New Zealand gaols he was generally disliked by his fellow convicts, who looked upon him as a mean, low, cowardly fellow, as he is described by the notorious Burgess. While at liberty in Christchurch light manual labour was found him, and it will be remembered that he contributed a series of scurrilous articles on 2Prison Experiences” to a now defunct Christchurch society paper.”

- December 1885: adverts appear in the Otago Witness ahead of the publication of Henry Garrett’s ‘Recollections of Convict Life in Norfolk Island with Prison Portraits, being Sketches of Prisoners and Prison Governors, Including The Early Life Career and Death of John Price, Billy Morgan, Burgess etc by Henry Garrett (Alias Rouse) To be commenced in the Otago Witness at an early date, due notice of which will be given.’

- 1885: Following Henry (Rouse) Garrett’s death in 1885 a number of newspapers in New Zealand carried stories of his life although his notoriety (then and since) seems to have affected the tone of the reports and some facts are certainly wrongly reported (for example, Bingham is sometimes recorded as Birmingham).

- As a prisoner, Henry (Rouse) Garrett wrote his memoirs; there was an attempt to publish these in the Otago Witness after his death but objections were raised (see news article samples, attached).

- Garrett is reputed to have almost beaten a fellow bushranger to death whilst in prison because the man had murdered a baby; histories often emphasise the ‘gentlemanly’ impulses of Rouse/Garrett. Reports in England are less romanticised.

- 1886: New Zealand Tablet publishes a strong criticism of its sister paper, The Otago Witness for publishing Henry (Rouse) Garrett’s memoirs; the criticism is heated, including:

- The content is ‘nasty and stupid … full of slang, abusive and libellous.’

- Libellous of the ‘late Mr Price cruelly murdered in 1857’ (Details of Price’s surviving family are given including Sir Charles Price of Cornwall and his son in the Royal Navy). This is the John Price described as a ‘cruel warder’ whose murder by fellow prisoners, Garrett claimed to have stood by and watched.

- Libellous of Mr Caldwell referred to as ‘Buttons’ in the account and libellous of an Otago Daily Times journalist who apparently gloated over witnessing a prisoner called Burgess being whipped following a charge of gross insubordination. Garret, in his account, objects to the humiliation of Burgess having a sack put over his head for the whipping but he does also explain that this was on the orders of the Gaol surgeon (Caldwell?) to preserve the anonymity of the officer carrying out the punishment (Caldwell?). The writer notes that Garrett has personal experience of Caldwell’s ‘saving’ Garrett from a sentence of twenty-five lashes with the cat’o’nine’tails following his attempt to murder one of the gaol officers with a poker.

- “One quotation we shall make from the highly objectionable fustian set forth by Mr Garrett and it is the following, “How easy it is for the press and police to manufacture a thief’s reputation or to destroy an honest man’s credit.” The Witness might take these words to heart and act upon the lesson they convey as to the position of a literary man he accords to a fellow described by one of the Judges of the colony as “a monster, a fiend, and a foul blot upon the page of nature.” He might also learn to refrain from allowing anyone to make use of his columns to place in the pillory honest men, and wreak the vengeance of a convict on them because they had done their duty. Mr Garrett, in fact, in these words we quote, conveys a lesson quite sufficient to close the columns of a respectable paper against his lucubrations, even, if those lucubrations in themselves were not disreputable and disgusting.”

- 16th June 1899: Otago Daily Times – letter containing corrections

- “Sir – I have read with much interest the series of articles in your columns from the Melbourne Argus on “The Goldseekers of the Early Fifties” In your issue of Saturday, the 10th, there appear several minor historical errors. Speaking of Garrett, his name was not “Tom”. The name he was best known by was “Harry Garrett”. His real name was “Henry Rouse”. The accompanying letter to Mr Donne, of Wellington, will explain more than I care to occupy your space with, and the only object I have in view is to give the future historian facts. Another error in the same issue was the capture of Garrett in England, which was solely due to the detective on the trail making friends with a woman that Garrett’s mate in the bank robbery had picked up. I am, etc, J. Forsyth. Manor Terrace, June 14th.”

- 15th October 1913 – Sydney Sportsman:

- “An “Old Hand,” recalling Henry Beresford Garrett, says:— “When at Dunedin, working in the prison gang, sometimes rain came on, and the prisoners would be marched into the railway station at Caversham for shelter. The stationmaster would allow Garrett to go to the office fire to warm himself on several occasions, for which favour Garrett was very thankful to Mr. Forsyth, the then stationmaster. In return, he said he would give him something that might do him some good. He gave his manuscripts, which, however, were not published till after his death, which occurred in 1880. The Otago ‘Witness’ published a good portion of them until an order obtained by Colonel Tom Price forbade the publication of any more in the newspaper. A horrible murder was committed in Dunedin— the Dwyers, father, mother, and a baby in the cot being the victims. The notorious Butler —not our infamous mountain criminal — was the reputed murderer. He confessed to arson, got a long sentence, and became a fellow prisoner of Garrett’s. “Butler confessed the murders to Garrett, who made a severe attack upon him with the leg of an iron bedstead, and only for timely aid he would have done for him. The killing of the baby was what roused him. Butler was hanged some time ago in Queensland for murder under the name of Warton.”

(KA = Kiwi Adventures: Woodside Glen and New Zealand’s Gentleman Highwayman)

Rouse Family Lineage

Henry Rouse’s convict record states that he was born in Bottesford, Leics:

- There is one birth record in the area for the appropriate dates:

- There is a baptismal record in Bottesford in March 1818 which is likely to be him (it tallies with reports of his later conviction and death (age 67 in 1885)). His parents are recorded as Thomas and Catherine Rouse.

- He is one of 4 children:

- Ann baptised in Bottesford, 13th November 1814

- James born 1816

- Thomas born 1817

- Henry born 1818

- There is a burial record for Catherine Rouse in Bottesford in 1821 (likely to be mother of Henry Rouse & his siblings)

- Marriage record for Thomas Rouse (widower) 6th November 1832 to Elizabeth Henton age 21 (both of Hose) – marriage license obtained.

- Elizabeth’s age on the marriage license doesn’t tally with later census records – it should perhaps read ‘of full age/over-21); the census records of 1841 and 1851 both give a birth date of 1783 and the 1851 Census records her birthplace as Frisby-on-the-Wreak, Leics.

- Elizabeth Henton was baptised in Frisby-on-the-Wreak on 14th July 1782.

- Banns are recorded for Thomas Rouse (son of Thomas and Catherine/brother of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) and Elizabeth Musson (both of Hose) in March 1838. The marriage seems to be recorded in the 1839 first quarter records for Melton Mowbray.

- Census 1841 (Hose) there are two Rouse households:

- Henry Rouse (age 20) is in the household of his father and step-mother in Hose.

- Householders are Thomas (age 60, farmer) and his wife Elizabeth (age 55) and Henry (age 20) – all are ‘born in County’.

- Thomas Rouse, age 25 (brother of Henry) is in his own household with wife Elizabeth, age 25 and newborn daughter, Charlotte.

- Oddly, there is no trace of either Ann or James Rouse in the 1841 census; later records imply that the brother and sister remained close throughout their lives.

- Henry Rouse (age 20) is in the household of his father and step-mother in Hose.

- There are records of Banns being read in 1842 for Henry Rouse (of Hose) and Jane Chester (of Harby) in both parishes; whilst Rouse is recorded in the Hose and Harby area at this time, his deportation records describe him as ‘single’. There is no marriage record – perhaps it didn’t proceed.

- Jane Chester: apart from theseBanns records, there is no trace, to date, of any confirmed information about who Jane Chester was or what happened to her after 1842.

- There is no trace of any birth record for Jane Chester (nationally).

- The Banns state that Jane Chester as ‘of Harby’.

- 1841 Census (Hickling): Jane Chester is in the Gill household (female servant, age 21, b.1820 ‘in County’). John Gill is a grocer and seems to be a widow with small children.

- Note: Henry Rouse seems to have links with Hickling via his accomplice Samuel Morrison.

- There are only 6 census records for Jane Chester (nationally) and the other 5 are all married women.

- Possible marriage record to John Jackson; 2nd July 1844 at St. Mary’s, Bingham. If so, she may be in Bilston, Leics in the 1851 census.

- There are death records for Jane Chester in the Melton District in 1852 and in 1863 (no further information).

- There is no sign that she followed Henry Rouse to Australia or New Zealand.

- Jane Chester: apart from theseBanns records, there is no trace, to date, of any confirmed information about who Jane Chester was or what happened to her after 1842.

- There are newspaper reports of his misdemeanours leading up to his deportation in 1845.

- Thomas Rouse Will 1851 (father of Henry (Rouse) Garrett – weak of body but sound in mind); contains family detail and bequests:

- Will is dated 14th November 1850 and probate granted June 1851.

- Daughter, Ann, is the sole executrix and residual beneficiary.

- His wife (Elizabeth) and daughter (Ann, spinster) appear to live with him on the farm; if they can continue to live together then Elizabeth is given an annual pocket money allowance but a bequest is made to Elizabeth if they choose to live apart.

- Proviso is made for both women staying on the farm and also for selling up.

- Provision is made for his three sons; James, Henry and Thomas – ‘should they return to England’.

- If the farm is sold, one third goes to his widow, Elizabeth Rouse; one third to his daughter, Ann Rouse; and the remaining third divided equally between his 3 sons, ‘when they return to England’.

- Note: Thomas Rouse (son) is listed in Hose with his family in 1851; it can be assumed he, at least, was ‘in England’.

- Note: James Rouse (son) appears to be living locally, too (possibly Upper Broughton); later records place him in Walton-on-the Wolds and Humberstone, Leics. Therefore, he also appears to be ‘in England’.

- Although the Will states ‘they’ when referring to the three sons/brothers, it appears that both James and Thomas were in England at the time of their father’s death (there are no migration or conviction records for either of them before this).

- Nevertheless, the idea of his sons not being ‘in England’ seems to have been important to Thomas Rouse and, indeed, Henry (Rouse) Garrett does journey back to England (at least twice?) after his deportation. Thomas (son) also emigrates with his family to Tasmania in 1885 – perhaps this was discussed before his father’s death and the move delayed until after his lifetime? There are continuous records of James Rouse remaining in the Leicestershire area until his death in 1884.

- There is no record that either James or Thomas was involved in any of their brother Henry’s criminal activities.

- 1851 Census (Hose): Thomas Rouse (father of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) is not recorded:

- Elizabeth Rouse – Head – Widow – age 68 (b.1783) – farmer of 59 acres – born Frisby-on-Wreake

- Ann Rouse – daughter – unmarried – age 36 (b.1815) – born Easthorpe (neighbouring Bottesford)

- It seems that Ann Rouse became a pastry cook (Nottingham) and then publican of the Anchor in Walton-on-the-Wolds before moving to live in the neighbourhood of her brother James in Humberstone, Leics (her Will in 1884 includes bequests to his children).

- There is a probable death record for Elizabeth Rouse in Hose, 1858.

- 1851 Census (Hose): Thomas Rouse (brother of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) and family – all born in Hose. Later records in Tasmania, Australia confirm Elizabeth’s maiden name is Musson (marriage record 1838):

- Thomas Rouse age 34 (b.1817) – Ag Lab

- Elizabeth Rouse age 34 (b.1817) – Ag wife

- Charlotte age 10 (b.1841)

- Mary-Anne age 6 (b.1845)

- Sarah age 4 (b.1847)

- James age 2 (b.1849)

- 1851 Census (Upper Broughton): possible census record for James Rouse – unmarried shepherd (age 32, b.1819, Hose) in the household of the Stokes family (originally from Hose).

- 1853: A news report into the ‘French Street Suicide’ places Ann Rouse as ‘in service’ in Nottingham; she requests to see the exhumed body of the suicide in case it is her brother, Henry; he is said to have recently returned to England and had unsuccessfully enquired after her (see timeline).

- Thomas Rouse (brother of Henry (Rouse) Garrett) and his family emigrate on the Ship Montmorency to Launceston, Tasmania, Australia arriving 28th June 1855 (as assisted migrants):

- This record corresponds with the 1841 census with the addition of a younger son, Robert (age 4).

- Elizabeth (nee Musson) Rouse died in June 1882, age 55 – ‘brain disease & general debility’. New Norfolk area of Tasmania.

- Birth record for Thomas Musson Rouse; 1859 Morven, Tasmania – confirming mother as Elizabeth Musson. There is a possible inquest record for him in 1906: “Heart inflammation, accelerated by a wound in the throat, but there is no evidence to show how the wound was inflicted”.

- There is also a marriage record in 1877 for his son James (also in Launceston) which implies that the family settled in the area.

- There is no trace, to date, of any contact between Henry (Rouse) Garrett and his brother, Thomas, after this move to Tasmania.

- 1858 Burial record for Elizabeth Rouse (Hose); age 68, buried in Hose churchyard 10th January 1858

- 1859 Marriage record – James Rouse (age 44) to Hannah Henson (age 27); Walton-Le-Wolds (both resident there at the time of the marriage).

- 1861 Census (Hose): the only Rouse household listed is that of John Rouse (born Hose, 1808) and his family (wife Mary) – farmer of 36 acres.

- This family was also listed in Hose in 1851.

- No clear/direct link to the family of Henry (Rouse) Garrett (possible cousins?).

- However, one of their children may be the Arthur Rouse listed with Ann Rouse as a cousin in Nottingham (1861) – he is with this family in 1851 but not in 1861.

- 1861 Census (St. Peter’s, Nottingham):

- Ann Rouse – Head – unmarried – age 46 (b. 1815, Easthorpe, Leics) – pastry cook

- Arthur Ed Rouse – cousin – age 13 (b.1848, Leics) – scholar (this may be the son of John & Mary Rouse of Hose (Census 1851 & 1861); if so, this confirms a relationship between the families).

- 1861 Census (Walton-le-Wolds): James and Hannah Rouse

- Initially, there seemed to be no trace of James and Hannah Rouse in the 1861 census; they appear in Humberstone in 1871 and 1881.

- However, their two eldest children are recorded as born in Walton (c.1861-63) making it likely that they were resident in Walton in 1861.

- James’s sister Ann Rouse is in Walton in 1871 – perhaps confirming the family link to the location.

- A search of the original images brings up a record for them; Christian names, dates and places of birth are all correct. Their eldest daughter, Louise is also listed (age 11months). It seems a safe assumption that the surname is Rouse.

- Transcription reads: James Parle, Hannah More, Louisa More.

- A number of servants are included in the household; as three of them share the surname ‘Page’ it is possible that they are a distinct household.

- Profession is illegible – not ‘ag lab’ as would have been expected; the transcription says ‘seamer […]’

- Interpretation isn’t helped by the fact that someone appears to have been playing ‘Hangman’ on the original record!

- 1871 Census (Walton-on-the-Wolds): Probable record for Ann Rouse (birth date given as 1803, born Hose). She is listed as unmarried and as publican of The Anchor, Town Street (licensed victualler) – only person in household.

- (see James Rouse – his two eldest children were born in Walton)

- 1871 Census (Humberstone):

- James Rouse – age 54 (b.1817, Hose) farmer of 230 acres

- Hannah Rouse – age 40 (b.1830, Sileby)

- 4 children (eldest son named Ambrose, later records show him as James Ambrose)

- The two eldest were born in Walton, Leics (see Ann Rouse, above).

- 1881 Census (Humberstone): Probable record for Ann Rouse (birth date given as 1803, born Hose). She is listed as unmarried and as a retired publican – only person in household.

- 1881 Census (Humberstone): James Rouse (widower) age 65 – farmer of 267 acres – employing 2.